The Parkman-Webster Murder: A Uniquely Boston Case

The convergence of Puritan values, attitudes toward immigration, and the prevalence of one university surrounding almost every aspect of the event, made the Parkman-Webster murder case a distinctively Boston story.

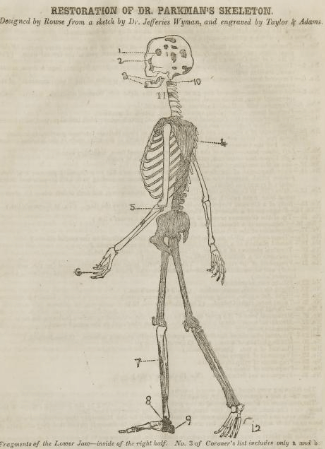

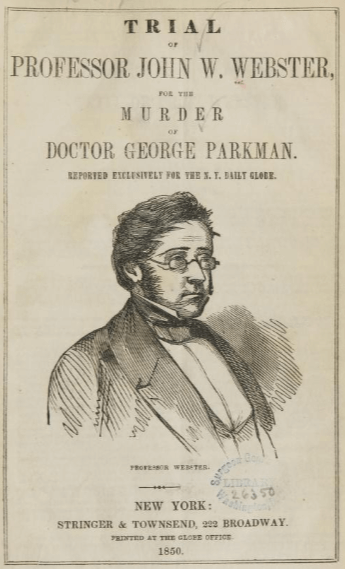

Prominent Boston physician, West End real estate mogul, and socialite George Parkman was seen leaving the grocery store on a brisk Thursday afternoon in November of 1849. It would be the last time he was seen alive. The search for the missing Parkman and discovery of his dismembered body in a Harvard Medical college basement laboratory shocked Boston. The later arrest and trial of his Harvard colleague John Webster garnered feverish attention, both at home and abroad. The Parkman-Webster case is often compared to the OJ Simpson trial due to the media frenzy and celebrity status of the parties involved. As in the Simpson case, class and ethnic conflict played a part in both the murder itself and the public perception of the events as they unfolded in 1849 and the following year.

In the two centuries after its founding in 1636, Harvard University became synonymous with the Boston elite who passed through its doors and into prominent positions in New England society. The Parkman – Webster case was a bona fide alumni reunion: both George Parkman (victim) and John Webster (suspect) were Harvard graduates, as was presiding Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw and three of the four attorneys. The odd man out was Prosecutor John Clifford who later served on Harvard’s Board of Overseers. In such overtly public roles, maintaining the appearances of a dignified socialite in 19th century Boston was almost as important as the role itself.

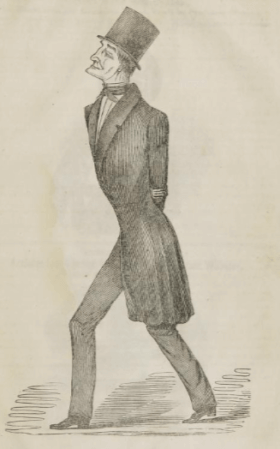

It was in this social realm where the two men of a seemingly similar standing faced a stark divide. The Parkman family had amassed considerable wealth through George’s father Samuel, who began as a merchant, trading silks and indigo in the India trade before diversifying into real estate and buying property throughout the West End. Upon Samuel’s death in 1824, George was given control of the family’s estate and continued to grow their fortune by investing in West End property. Even up to the day of his death, he could be seen in his signature top hat and long coat strolling through the city to personally collect rent from his tenants.

Meanwhile, John Webster did not even own his family home at the time of the murder, instead leasing the house of a family friend. Webster’s father, Redford, took on a more subdued career as an apothecary, providing medicine and instruments to a swath of New England physicians, among them Harvard Medical School founder John Warren. He later served in the state legislature, but still left only a small inheritance to his son. Webster’s lower financial position compared with his peers would later be used against him.

During the trial, prosecutors made public to a courtroom full of his Harvard peers and the enraptured public, that Webster lived far beyond his modest salary as a Harvard chemistry professor to maintain the reputation expected of a ‘Harvard Man’. Webster was so deeply in debt to Parkman when the deadly altercation occurred that he had mortgaged nearly all his belongings – clothing, art, furniture – to Parkman. It was speculated the confrontation was spurred on when Parkman discovered Webster had fraudulently pledged the same mineral chest as loan collateral to both him and another group of Boston financiers simultaneously. These revelations, and the ensuing fallout, highlighted both the extent of Webster’s debt, and the principled approach Parkman took in protecting his family’s wealth. The contrast that laid beneath this gilded surface ultimately doomed Webster, and by tragic extension, Parkman.

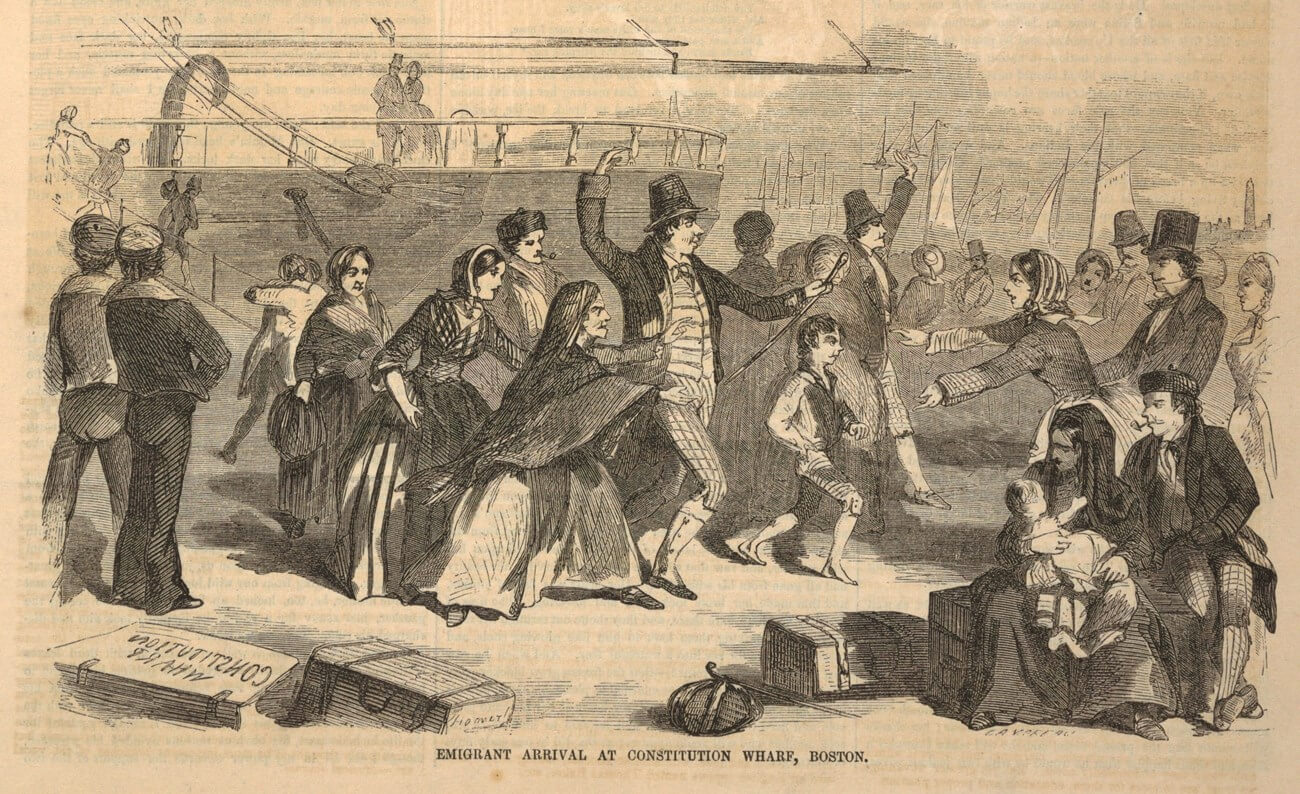

Boston’s Puritan traditions, imprinted upon generation after generation of its leading families, lasted long after the city’s founding in 1630. The city largely maintained its Protestant identity into the early stages of immigration leading up to the 1850’s, and was even invigorated by the Second Great Awakening that touched Boston in the early 1840s, preaching abolition, social reform, and temperance. By 1852, however, increased Irish immigration due to the potato famine caused a profound demographic shift in the historically Protestant city. Many of the Irish, who now accounted for 26% of Boston’s 136,000, were impoverished farmers. Lacking sufficient infrastructure to support these new arrivals, the city saw a rise in disease, mortality, and crime. A predictable clash occurred between the Protestant upper class fixated on reform, and the growing Irish working class population which became the target of their misgivings.

Parkman’s high-profile disappearance – later compounded by Webster’s arrest – fed conveniently into critiques of Boston’s supposed moral decay at the hands of the Irish. When Parkman was first reported missing, Boston police, led by Marshal Francis Tukey, began a sweep of the city’s poorest neighborhoods believing he had been robbed and murdered by Irish immigrants. As tips began to pour into the police and newspapers, several eyewitness accounts pinned Parkman with an Irishman walking along the Longfellow bridge before disappearing shortly after. Even upon Webster’s arrest – formally framing the scenario as a murder of a Brahmin, by a Brahmin – the newest Bostonian’s were still treated as scapegoats, guilty of bringing even the city’s most distinguished citizens down with them into crime and depravity.

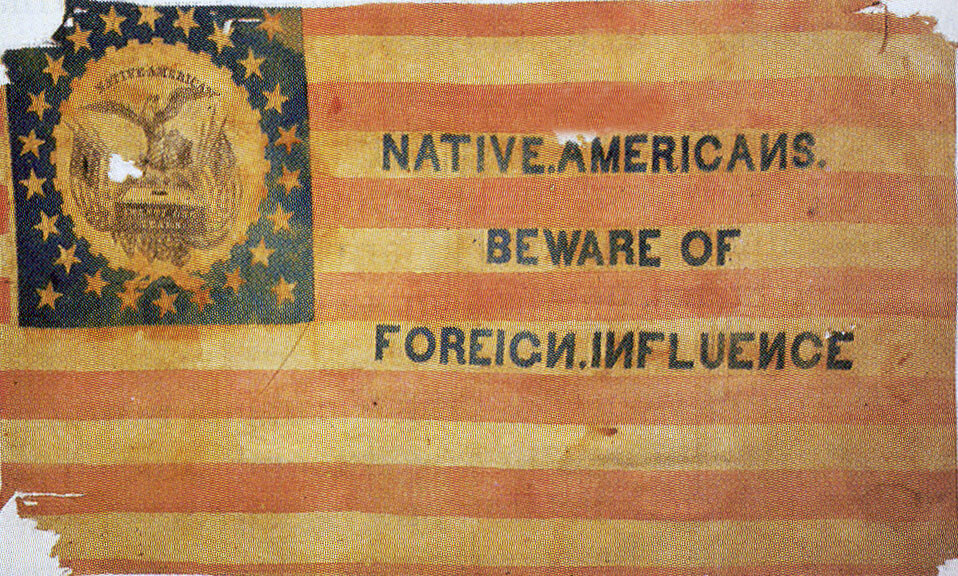

The broader societal themes at the center of the Parkman-Webster case were crucial, and by no means unique to Boston or that particular point in time. As Irish immigration continued into the 1850s, nativist sentiments during the period gave rise to the American political party (often referred to as the Know-Nothings, because when asked about the party, members were supposed to say they knew nothing), whose platform included immigration restriction and other thinly veiled racist policies seeking to eliminate outside influences in the country. Meanwhile, as passing decades eroded the influence of America’s founding families, a new upper class fueled by the industrial market economy surpassed the wealth of their aristocratic predecessors, widening the chasm between elite educated professionals and the burgeoning capitalists – called Associates in Boston – who would come to define America’s Gilded Age. However, it is without a doubt that the specifics of the case – a trial fraught with Harvard men, a murder on the grounds of present day Mass General Hospital, all judged through the lens of a distinct Puritan righteousness – cemented the curious case firmly as a uniquely Boston story.

Article by Meyer Aviles edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources :https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/11/resources/8787; https://www.massmoments.org/moment-details/professors-murder-trial-begins/submoment/dr-george-parkman-disappears.html; https://www.britannica.com/topic/Know-Nothing-party; https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/ethnic-groups/irish/; https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/murder-bostons-immigrant-population/; https://www.newspapers.com/clip/8314309/dr-webster-lived-in-jonas-wyeths/; Collins Paul. 2019. Blood & Ivy : The 1849 Murder That Scandalized Harvard. New York N.Y: W.W. Norton & Company.