The Sailors of Scollay Square

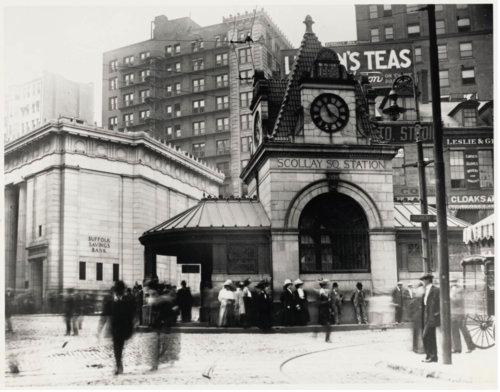

Scollay Square was a popular Boston hot spot for nightlife during the first half of the 20th century, with its vaudeville theaters, bars, and sideshow attractions. Long chided by local politicians for its perceived physical and moral decay, in 1963 the City of Boston completely demolished the area as part of an urban renewal project. Though often viewed within the broader context of the West End’s redevelopment, Scollay Square’s final chapter can also be understood through the lens of World War II, the growth of Boston’s Navy Yard, and the demographic shifts at the war’s conclusion.

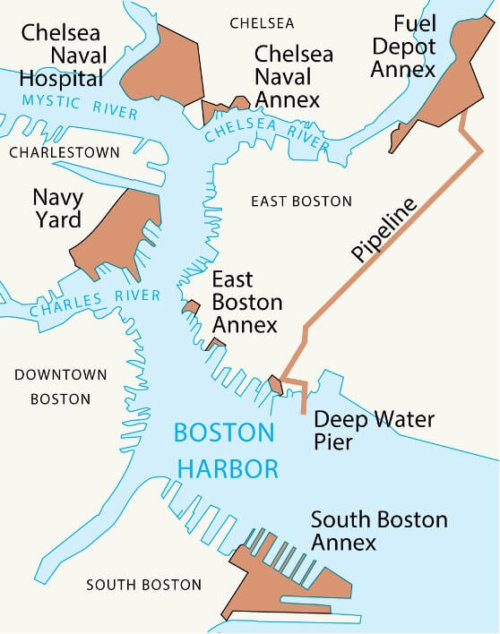

A modest naval presence at Charlestown Navy Yard following World War I ended in 1932 when the United States Navy designated the location as a future building site for destroyers. The first new ship, the USS McDonough, splashed into the harbor in 1934, spurring a rapid period of production and activity at the Yard. When Europe plunged into conflict five years later, Boston served as a strategic repair site in the North Atlantic for escort ships protecting American goods sent overseas to support the British war effort. Despite America’s initial neutral stance, the fall of France in June of 1940 heightened its commitment to the Allied Powers. In the coming months, the Boston Navy Yard outfitted 18 dormant American destroyers for Royal Navy use while infrastructure projects increased the harbor’s productive capacity. Over a short period, the Naval labor force in Boston ballooned from 3,875 in 1939 to 18,272 in the summer of 1941. When America entered World War II that winter, Boston drew in even more shipbuilders and became a frequent departure and entry point for sailors enlisted in combat.

Scollay Square sat only a 12-minute subway ride across the harbor from the Navy Yard, earning a strong reputation amongst West Enders and Bostonians at large as a haunt for young men looking to enjoy their “liberty time” on American soil. Eager sailors would run up the subway steps and out onto Court Street for a carefree night on the town where “Boston’s Barbary Coast” offered bars, restaurants, tattoo parlors, and burlesque theaters at low prices. Businesses such as the Old Howard Theatre, Joe & Nemo’s hotdogs, and Waldron’s Casino enthusiastically served their maritime patrons. Although the area was not popular with Boston-raised sailors (who had usually run the gamut of the square back in their high school days), anecdotes of its trappings spread across the Atlantic and Pacific by servicemen who were newly of drinking age and had never left home before the war. According to David Kruh, author of Always Something Happening: A History of Boston’s Infamous Scollay Square, naval ships passing each other would sometimes signal, “How are things in Scollay Square?”

While entire cities like San Diego and Portsmouth became known as Liberty Towns for off-duty soldiers, the small district of Scollay Square earned the moniker on its own and was often a subject in popular media, including a 1952 Pearl Schiff romance novel of the same name. The area became a near-extension of the Charlestown Navy Yard, as sailors spent their monthly wages on photo booths, nightclubs, and hotels. While Boston police defended the reputation of the sailors – promising “not one (had) ever accosted a girl or was charged with a sex offense” – the area was so saturated with Navy personnel that the presence of the Shore Patrol, monitoring sailors who had a little too much to drink, became commonplace in Scollay Square. The sheer number of wide-eyed out of towner’s brought con men into the streets of the area, peddling fake jewelry on any naive sailor who gave them the time of day. Scollay Square’s particular clientele during wartime gave the area a distinct energetic feeling that could not be replicated in other areas of the city.

Predictably, World War II’s conclusion in 1945 spelt trouble for Scollay Square and the businesses that lined its curving streets. The nightlife district’s primary customer base returned home after the war from outposts across the world, no longer passing through Boston before deployment or between assignments. The once-bustling Charlestown Navy yard was reduced to a ship repair facility, and the bars, parlors, and shops once relying on the influx of servicemen to the Square now lacked a reliable source of income. On a wider scale, postwar suburbanization eroded consumer and business bases of downtown areas all across the United States. Boston was no exception – as young families left the urban core between 1950 and 1960, the city population decreased by over 100,000 citizens and was further diminished when 46 acres of neighborhood were razed during West End redevelopment. Scollay Square already began to lose its identity with the loss of its maritime patrons; suburbanization only served to further accelerate its decline. By the end of the 1950’s, the Old Howard had long shuttered its doors and the increasingly barren neighborhood became the target of redevelopment efforts to “purify” the area. By the 1960’s, the brutalist complex of Government Center took its place and as the Boston Globe noted, “only the ghosts of the crews ashore for a night on the town will loiter,” as the vibrant commercial district was reduced to imposing civic buildings.

Scollay Square was known long before World War II as a transportation, shopping, and theater center, but stands out in recent memory as a sailor’s hideout during World War II. In a twist of fate, the very patronage of the young servicemen it catered to motivated the officials of a stubbornly Puritanical city to reform the district and its seedy reputation. Small remnants of the nightlife hub remain in the form of the “Scollay Under” mosaic sign uncovered during construction in 2014, (now emblazoning the wall of the Government Center MBTA station), as well as the plaque in Pemberton Square marking the site of the Old Howard. As memory of its heyday in the 1940’s dims further and further, these artifacts are increasingly becoming all that remain of the formerly beloved area.

Below are some additional structures which may be useful on occasion.

Article by Meyer Aviles, edited by Bob Potenza

Source: https://lostnewengland.com/2016/03/scollay-square-boston-2/; https://sites.tufts.edu/govcenter/1-introduction/; https://www.boston.com/culture/lifestyle/2016/03/22/scollay-under-government-center-signs/; https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-boston-navy-yard-during-world-war-ii.htm; https://www.upi.com/Archives/1987/04/05/Once-risque-Scollay-Square-regains-its-old-name/2607544597200/; Kruh, David. “Always Something Doing,” 1999.