The Settlement Movement

The settlement movement was an attempt by scholars and social reformers on both sides of the Atlantic to address the problems caused by industrialization, urbanization, and, in America’s case, the mass immigration of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Settlement Houses were important institutions in Boston’s West End, assisting families with a wide range of educational and social services.

The settlement movement originated in England with the work of Frederick Denison Maurice and Cambridge University graduate students, who together in 1854 established the Working Men’s College in London: a “joint effort for the improvement of social conditions.” Influenced by the earlier work of Maurice, Samuel A Barnett, vicar of St. Jude’s Parish, Whitechapel, opened the first recognized settlement house in 1884 at Toynbee Hall in a working-class neighborhood of East London. His concept was to have his social workers (mostly university students) live amongst the working-class poor while assisting them in dealing with the “crude handicaps of life” through education and social programs. This way, workers would come to understand the people they supported and better appreciate their challenges. Barnett’s ultimate goal was to improve relations between the classes.

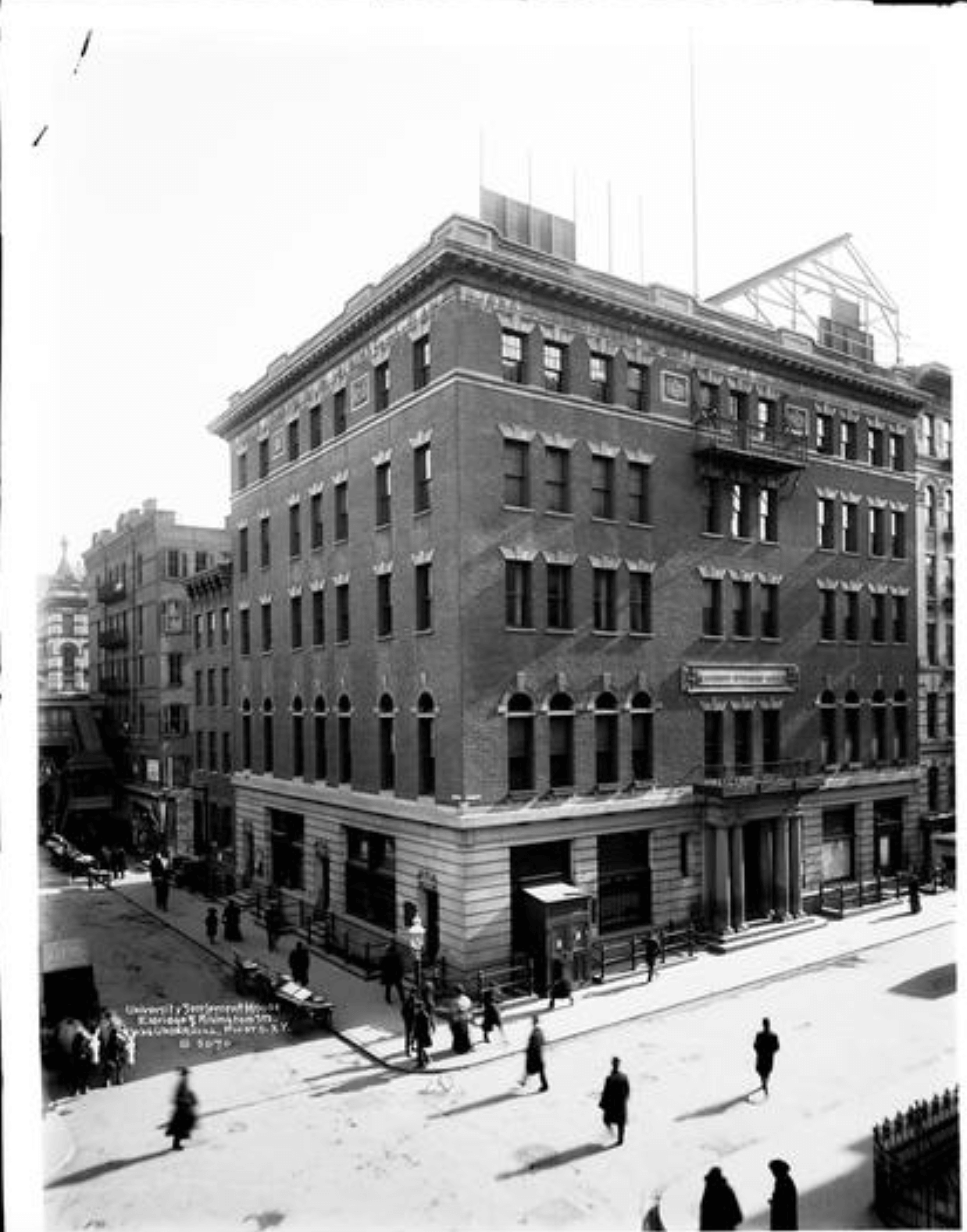

Upon hearing of these experiments, American social workers, such as Stanton Coit, Jane Addams, and Robert Archey Woods, visited Toynbee Hall to study its methods with the hope of applying such practices at home. After returning from England, Coit founded the first settlement house in the United States, Neighborhood Guild (later renamed University Settlement), in New York City in 1886. Three years later, Jane Addams, a pioneer in American social work, with her colleague Ellen Gates Starr, established Hull-House in Chicago. The number of settlement houses in the United States grew from 75 in 1897 to over 400 by 1910 in direct response to the rise of the immigrant population in major cities.

Assisting immigrants in adjusting to life in their new country became a distinctive feature of American settlement houses. They offered language and civics education, health care services, and employment assistance, and also established agencies, such as legal aid societies and special banks, to protect immigrants from rampant prejudice and exploitation. Many houses walked a fine line between supporting the national identity of immigrants and pressing for quick Americanization, a fact noted by critics and the National Federation of Settlements itself.

Boston’s first settlement house was led by Robert Archey Woods, a theology student at Andover Theological Seminary in Andover, Massachusetts, who spent six months studying Toynbee Hall in 1890. In 1891, upon his return to the United States, Wood’s former instructor, Professor William Jewett Tucker, recruited him to head Andover House (later renamed South End House) at 6 Rollins Street in Boston’s South End. Here, the focus was on the immigrant working class community, and the South End House provided a number of educational and counseling services. Decades later, South End House became an association consisting of five properties. Two of them, located in Woburn, Massachusetts and Poland Springs, Maine, provided camping opportunities to city children. Woods was also the editor of Americans in Process (1902), a study on the conditions of the North End and West End neighborhoods.

The West End had a number of settlement houses. Its first, the Elizabeth Peabody House (EPH), was founded in 1896 by friends and colleagues of Elizabeth Peabody, founder of Boston’s first kindergarten. Initially, EPH served as a kindergarten and offered a pasteurized milk program for immigrant mothers. After moving to a larger facility at 357 Charles Street, it expanded its scope: EPH added science labs, a theater, and a gymnasium, and began hosting summer camps. In 1903, a club founded by immigrant boys “to pursue mental, moral and physical advancement” became the West End House. James J. Storrow II, Boston philanthropist and politician, was impressed by the boys and bought them a home for the club in 1906 at 9 Eaton Street. It would eventually take on the name West End House and become a chapter of the Boys Club of America. West End House was organized into numerous member-run clubs focused on leadership, education, and athletics. Other West End settlement houses included: the Heath Christian Center; a Baptist church mission in Bowdoin Square; and the Hecht House, originally the Hebrew Industrial School.

The enduring success of the settlement movement is evidenced by the continued operation of many settlement houses over a century after their establishment. The South End House eventually merged into the United South End Settlements, a South End neighborhood center focused on youth programs, local art, and community outreach. The Elizabeth Peabody House and West End House survived as organizations after the demolition of the West End during urban renewal in the 1950s: EPH moved to Somerville and the West End House is the largest youth development agency in the Allston-Brighton community.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: “About Us”; “Apr 16, 1896, Page 5 – The Boston Globe at Boston Globe”; “Apr 21, 1896, Page 5 – The Boston Globe at Boston Globe”; “Collection: Boston YMHA-Hecht House Records | Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center”; “Collection: Boston YMHA-Hecht House Records | Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center”; “Collection: South End House (Boston, Mass.) Records | HOLLIS For”; “Dec 29, 1891, Page 4 – The Boston Globe at Boston Globe”; “Feb 12, 1896, Page 8 – The Boston Globe at Boston Globe”; “Guide to the South End House Association Records,1909-1944”; “May 03, 1892, Page 9 – The Boston Globe at Boston Globe”; “Oct 12, 1895, Page 8 – The Boston Globe at Boston Globe”; “Settlement Houses in the Progressive Era”; “The Elizabeth Peabody House Celebrates 125 Years of Impact”; “The History of Toynbee Hall – A Timeline – Toynbee Hall”; Albert Joseph Kennedy, Handbook of Settlements; Addams, Twenty Years At Hull-House; Robert A. Woods and Albert J. Kennedy, The Settlement Horizon; Philanthropy and Social Progress; Seven Essays; Streiff, “Boston’s Settlement Housing”; “Settlement Houses.”