The Visionists: The Bohemians on Pinckney Street

The Visionists were a group of bohemian writers, artists, and architects based primarily along Pinckney Street on the North Slope of Beacon Hill. Modeling their work after the arts and crafts movement, theosophy, and aestheticism. The short lived group left a mark on photography, the fine press, and Boston’s bohemian arts scene.

The Visionists of Boston were a loosely-aligned Bohemian circle of artists and writers. They shared a passion for spiritual inquiry, aestheticism, and the transformative power of art. As artists, intellectuals, and social reformers, they sought a return to creativity, beauty, and craftsmanship. This was largely a reaction to late 19th century industrialization. Several members lived on and hosted meetings on Pinckney Street in the West End. The Visionists helped to define a unique cultural moment in Boston’s history. Moreover, they influenced broader American trends in literature, architecture, and visual art.

Origin of the Visionists

Like many cities, Boston in the 1890s was experiencing profound economic and cultural change. Industrialization, urban growth, and shifts in population had forever altered the city. The rapid changes in American life provoked several responses. Some turned to conservative backlash and others embraced emerging Bohemian subcultures. While many upheld Boston’s Puritan legacy, institutions, and mercantile values, others sought alternative inspirations. Following the aesthetic movement in Britain, a new generation of artists came into their own. They celebrated artistic and religious freedom, spiritual awakening, and a return to the craftsmanship they felt was getting lost due to industrialization.

Boston at the time had a lively network of (male-dominated) artistic and social groups. One of the larger social groups was called The Association of the Pewter Mugs. A select, highly artistic group branched off from the Pewter Mugs to form the Visionists.

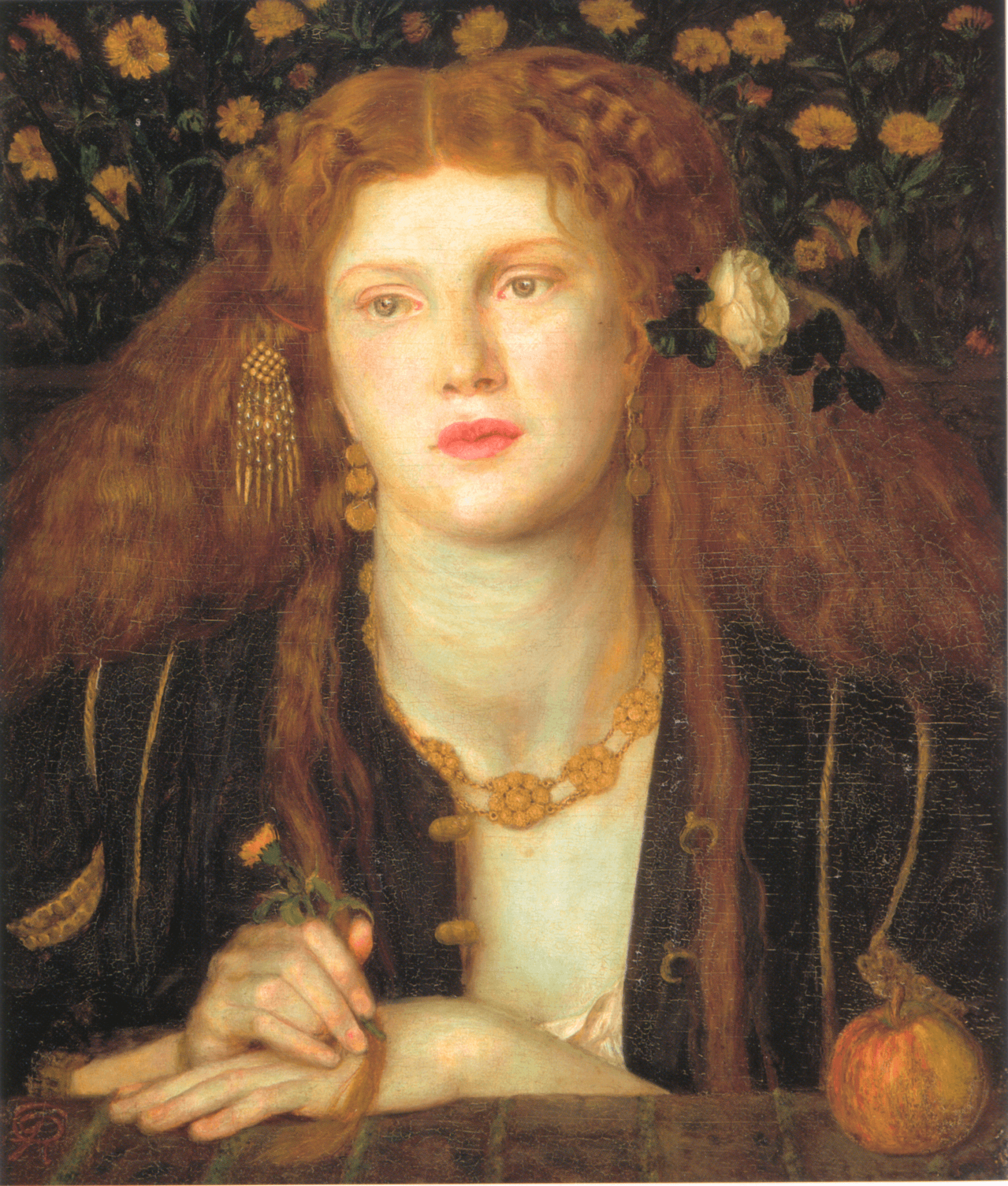

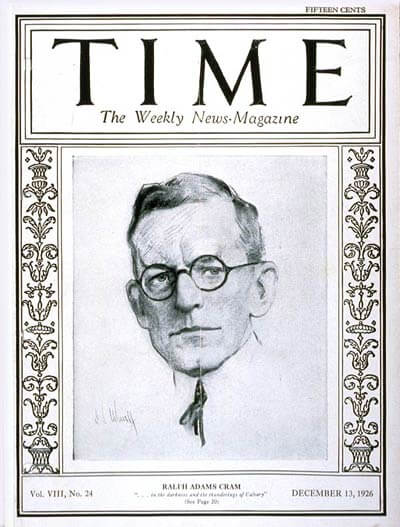

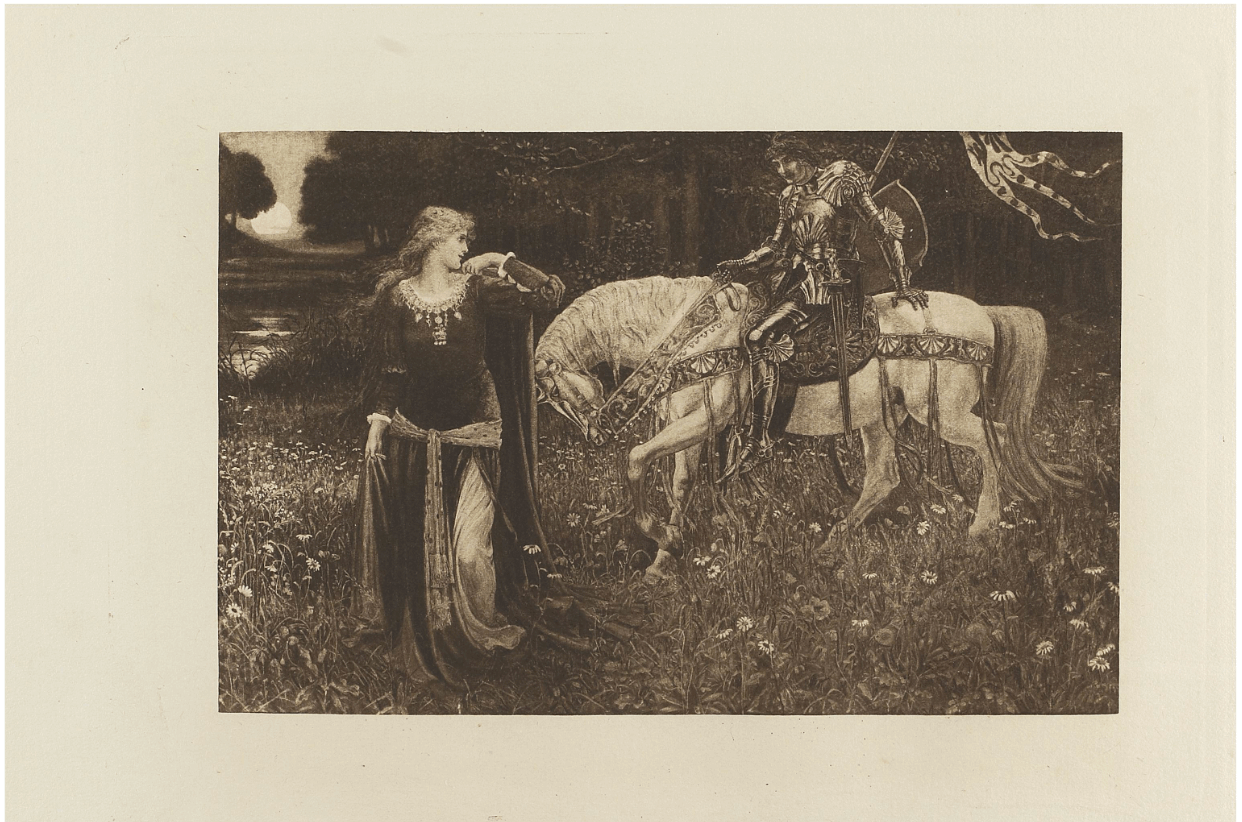

A circle of around twenty members centered around writer and architect Ralph Adams Cram. The group bonded through shared interests and influences such as writer Oscar Wilde, the aesthetic movement and pre-Raphaelite painters. They followed William Morris and his Arts and Crafts movement. They read works by the spiritualist H.P. Blavatsky about her Theosophy movement. Many courted spiritualism and expressed concerns about the consequences of urbanization and mechanization.

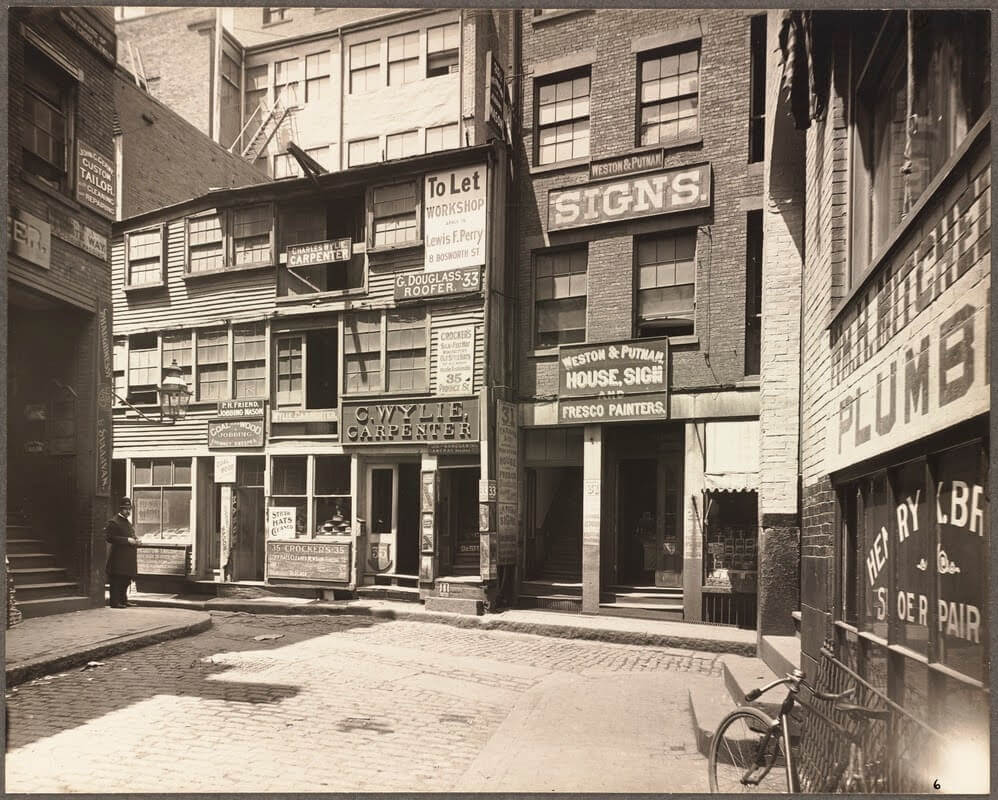

The Visionists began meeting in a rented space at 3 Province Court, a downtown alleyway described by Ralph Cram as “disreputably decadent” . A Boston Globe writer remarked that the clandestine spot was a place where, “you would never dream of hunting for anything more ethereal than sneak thieves and cobwebs.”

Later, homes of members of the Visionists on Pinckney Street in the West End became a frequent gathering place.

Core Group of Boston Visionists

- Ralph Adams Cram

- F. Holland Day

- Louise Imogen Guiney

- Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue

- Bliss Carman and Richard Hovey

- Other Members

Ralph Cram (1863 – 1942) was the child of a Unitarian minister of modest means. He moved from Hampton Falls, New Hampshire to Boston in 1881 to apprentice in an architect’s office. He went on to become a well-known ecclesiastical architect who popularized Neo-Gothic designs. He was appointed the head of the Department of Architecture at M.I.T. Local buildings he designed include the John W. McCormack Post Office and Courthouse, All Saints Church in Dorchester, Christ Church in Hyde Park, and All Saints in Brookline.

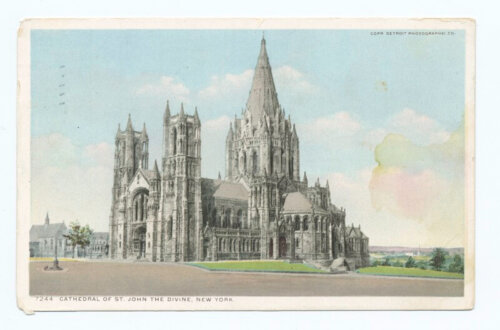

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City and the Princeton University Graduate College are also among his many designs.

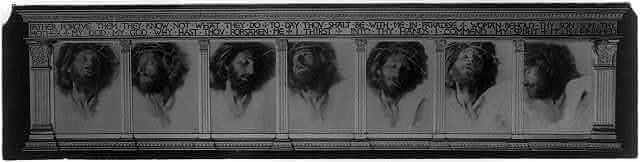

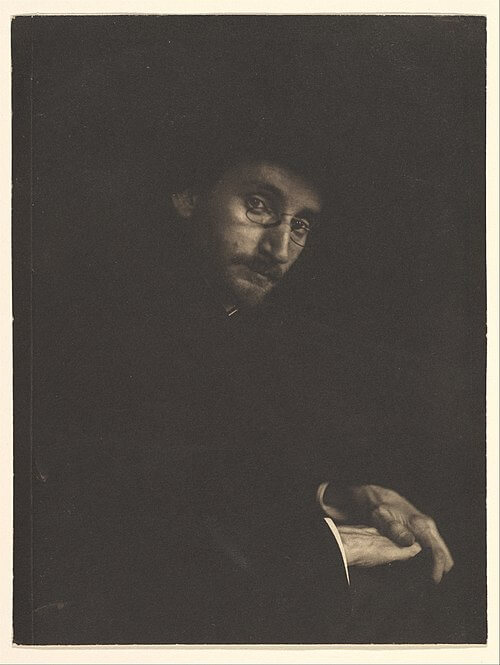

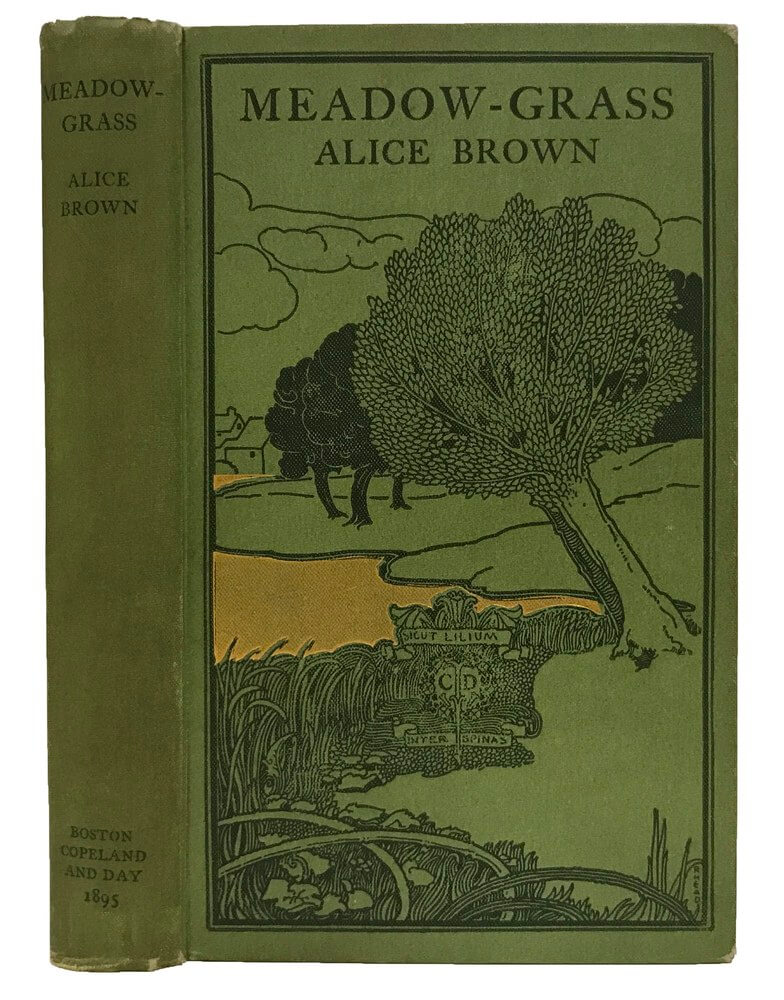

Fred Holland Day (1864 – 1933) from Norwood, MA was a photographer and publisher. With Herbert Copeland, he founded a small press, Copeland and Day – the American publishers of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. He would become one of the most influential American photographers at the turn of the 20th century. His practice was key in the establishment of photography as fine art.

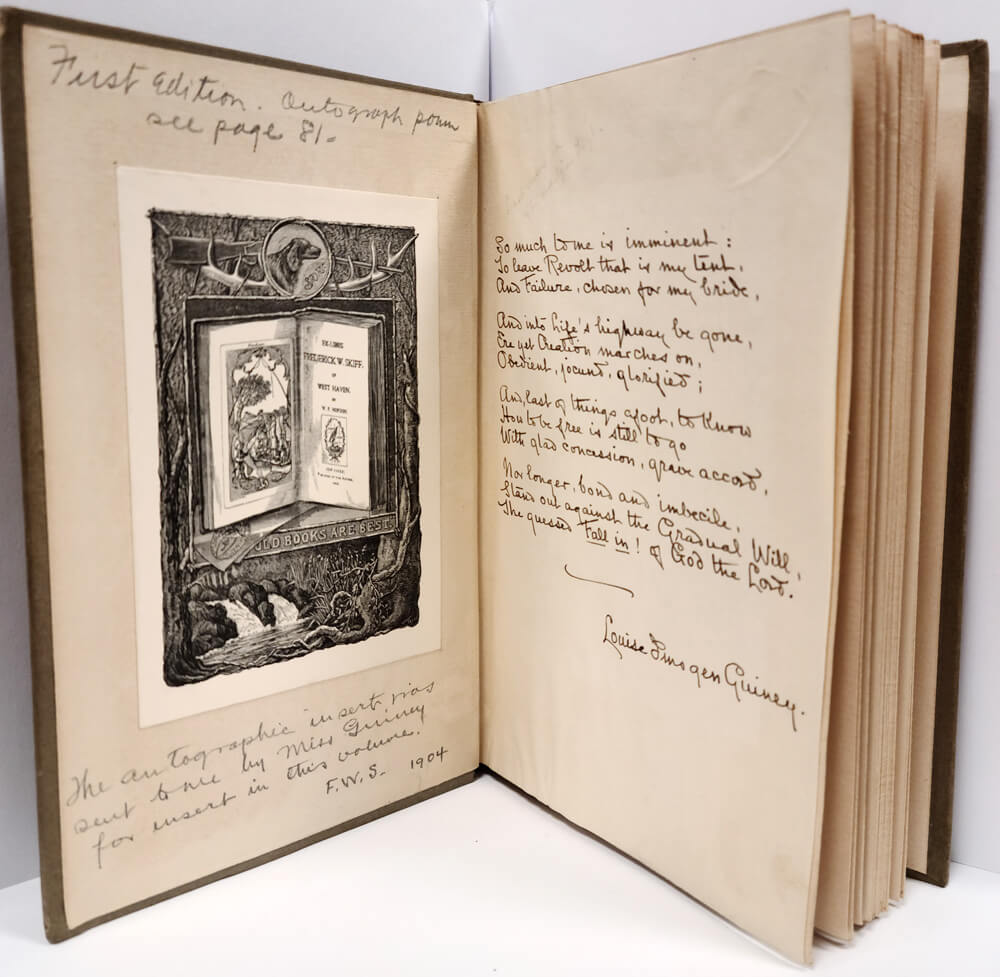

Louise Imogen Guiney (1891 – 1920) was a poet who introduced her good friend F. Holland Day to Cram. Born in Roxbury, she was one of few women, along with writer Alice Brown (1857 – 1948), associated with the Visionists. She struggled to support herself and her mother and worked at the post office and library while writing at night. Guiney and Brown maintained an intimate romantic friendship for many years.

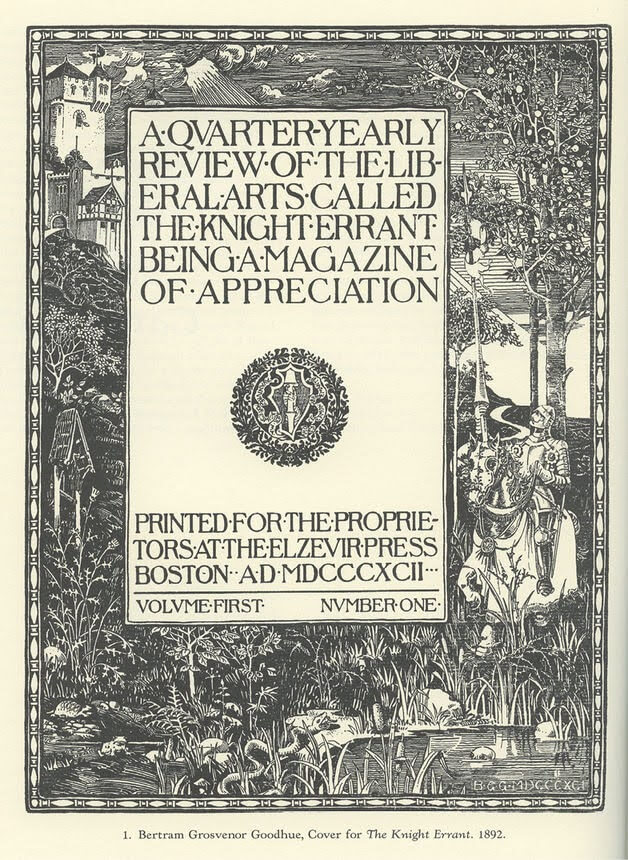

The Visionist journal The Knight Errant took its name from one of Guiney’s poems, included in the first issue. She moved to England in 1901.

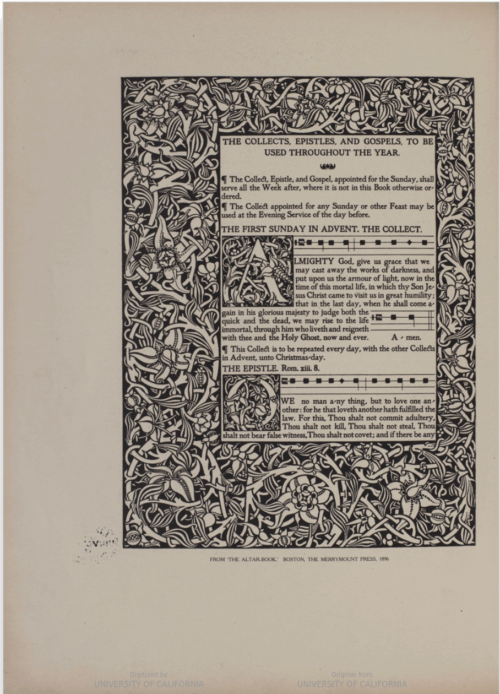

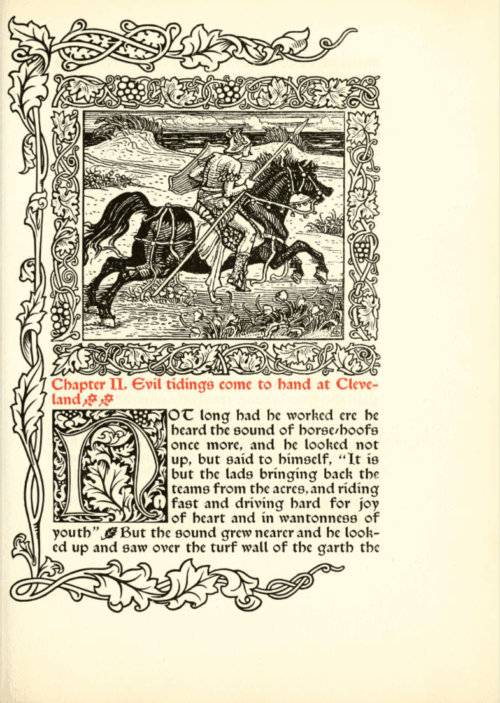

An artist and architect from Connecticut, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (1869 – 1924) began his architectural career at fifteen as an apprentice to the architect of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. He became known for his extraordinary artistic ability and ornamental Gothic design. He was an expert of medieval book construction and a creator of the Cheltenham typeface used today by the New York Times .

He would eventually design the Los Angeles Central Library and buildings at Yale, West Point, and other universities.

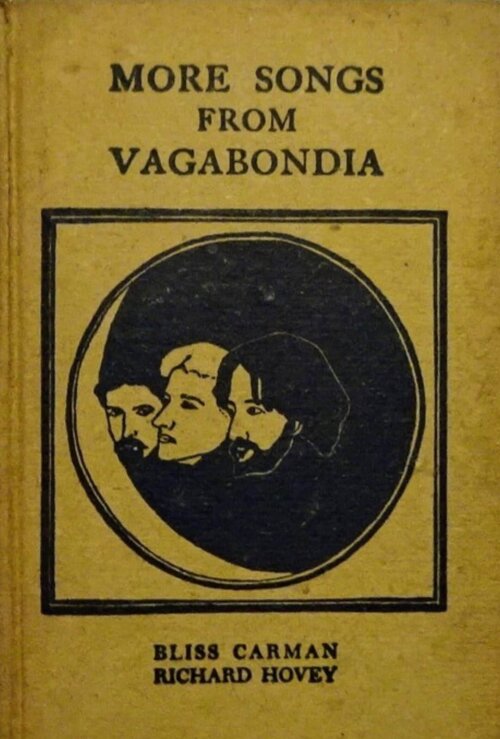

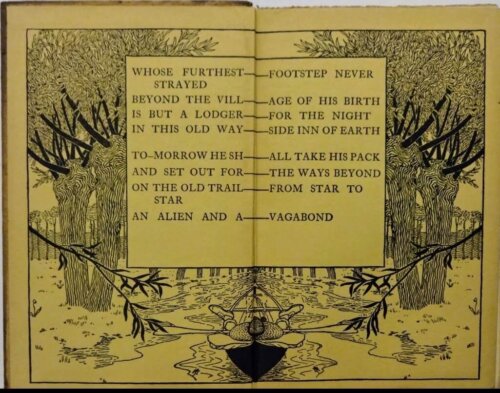

Bliss Carman (1861– 1929) was a Canadian poet who spent most of his life in the United States. He was later informally called the poet laureate of Canada. Richard Hovey (1864 – 1900) was a Dartmouth College-educated poet who worked with Carman. Hovey was the author of Dartmouth’s alma mater. Together the poets collaborated on the Vagabondia collection of poems that bridged literary innovation and visual presentation. Copeland and Day published the collection which went on to be a great success.

Other active members of the group include publisher Herbert Copeland (1867–1923), photographer Francis Watts Lee (1867– 1945), illustrator Thomas Buford Meteyard (1865– 1928), composer Frederic Field Bullard (1864 – 1904), novelist Alice Brown (see Guiney) and writer Jonathan Thayer Lincoln (1869 – 1942).

Visionist Collaborations

The members of the Visionists worked together on several projects. Bertram Goodhue became a partner in Cram’s architectural firm. Bliss Carman and Richard Hovey created the Songs from Vagabondia series together. The group created two journals – The Mahogany Tree and The Knight Errant. The latter was published between 1892 and 1893. It celebrated elegant design, literary innovation, and a rejection of commercial culture through the craft of beautiful printing. Though it only published four issues, it is recognized as being responsible for a revival of fine book-making in America.

On Pinckney Street

Pinckney Street in the late 1890s had the reputation of being a Bohemian enclave. Many of the street’s residents were literary, idealistic, and led unconventional lives.

Several members of the Visionists lived on the street and social gatherings were frequent. Ralph Cram lived at 99 Pinckney. Louise Guiney lived with novelist Alice Brown at 11 Pinckney. Finally, F. Holland Day lived at 9 Pinckney Street. The Visionists believed in art as lived experience. Their immersive celebrations often blurred boundaries between performance and communal artmaking. They decorated their rooms with Japanese prints, fragments of decorations rescued from demolished churches, and each other’s art. Costumes were often worn for theatrical presentations and staged photographs.

The Visionists disbanded as an identifiable group in the early years of the 1900s. However, their individual achievements continued to influence culture. Members Cram and Day would shape American architecture and photography well into the new century. The group insisted on artistic integrity, craftsmanship, and dialogue across disciplines. This attitude anticipated modernist and avant-garde art that would gain prominence decades later. Today, many share the Visionists’ enduring belief that art and beauty can redeem modern industrial life.

Article by Janelle Smart, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources:

Emma Beckman, “Faces & Places: LGBTQ+ History in the West End” (The West End Museum, October 17, 2024) | “F. Holland Day,” (The West End Museum, August 28, 2024); D. M. R. Bentley, “CARMAN, WILLIAM BLISS (Bliss Carman),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003; The Boston Globe Sun, Mar 19, 1893 ·Page 17; Britannica Editors. “Richard Hovey”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 30 Apr. 2025; William Buckingham, “The Architecture of All Saints,” (Parish of All Saints, Ashmont); Carpe Librum Books “The Boston Visionists: Letters of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue to F. Holland Day”; Delaware Art Museum, “Copeland and Day” in The Cover Sells The Book: Transformation in Commercial Publishing 1860-1920 (Delaware Art Museum, digital exhibition); Rebecca Jeffrey Easby, “The Aesthetic Movement,” in Smarthistory, June 3, 2016; Patricia J. Fanning, Through an Uncommon Lens: The Life and Photography of F. Holland Day (University of Massachusetts Press, 2008); Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, A Book of Architectural and Decorative Drawings, (NY: The Architectural Book Publishing Company, 1914); Josh Kastorf, “The Visionists of Boston: An online museum of Boston’s lost bohemia”; The New York Landmarks Conservancy, “Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine” ; The Norwood Historical Society, “F. Holland Day House”; Poetry Foundation, “Louise Imogen Guiney”; Douglass Shand-Tucci, Boston Bohemia 1881-1900 (University of Massachusetts Press, 1995); Janelle Smart, “Spiritualism in Boston,” (The West End Museum, May 23, 2024); The Tate Gallery, “Pre-Raphaelite” ; Thomas J. Watson Library and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Knight Errant, (JSTOR).