Urban Renewal in Boston’s Charlestown Neighborhood and Lessons Learned from the West End

Boston’s urban landscape has been dramatically shaped by urban renewal initiatives of the mid-20th century. Among the most notable examples are the West End and Charlestown—two historic neighborhoods with starkly divergent urban renewal results. While the West End became the poster child for urban renewal’s destructive potential, Charlestown had a very different outcome only a few years later. This article examines these contrasting urban renewal experiences, highlighting their implementation approaches, community responses, and lasting impacts on Boston’s urban fabric.

In the 1950s, the West End was a vibrant, densely populated immigrant neighborhood characterized by its ethnic diversity and tight-knit community bonds. Home to Italian, Jewish, Polish, and Irish communities, the area was viewed by city planners and developers as a “slum” ripe for redevelopment despite being a functioning, socially cohesive neighborhood like many others (including Charlestown).

The West End urban renewal plan, approved in 1958, was devastating in its thoroughness and speed. The Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) designated the entire neighborhood for clearance, displacing approximately 7,000 residents. Over 300 buildings were demolished across 46 acres, effectively erasing a historically significant working-class immigrant enclave from Boston’s map.

The West End project exemplified the “bulldozer approach” to urban renewal that was very typical of the early implementation of the 1949 Housing Act. City officials and planners justified the wholesale destruction by portraying the neighborhood as blighted and substandard, despite evidence to the contrary. Residents received minimal notice before eviction, insufficient relocation assistance, and inadequate compensation for their homes. The brick row houses of the West End were replaced by Charles River Park, a series of luxury high-rise apartment buildings surrounded by open spaces that bore no resemblance to the neighborhood’s former character—nothing in the 1949 Housing Act mandated the construction of low- or moderate-income housing. These new developments catered to affluent residents, pricing out the former inhabitants and creating a sterile, suburban-style enclave in the heart of the city.

The West End renewal embodied a top-down planning approach with almost no meaningful community input. The process was largely controlled by powerful interests—developers, politicians, and institutions that saw an opportunity to remake valuable urban land near downtown Boston.

Charlestown’s urban renewal story unfolded quite differently. Like the West End, Charlestown was a working-class neighborhood with a strong Irish-American identity dating back generations. When urban renewal plans were proposed for Charlestown in the 1960s, the BRA initially envisioned large-scale demolition similar to the West End approach. However, Charlestown’s urban renewal process diverged significantly for several reasons.

First, by the time Charlestown’s renewal began in earnest, the West End’s destruction had already occurred, serving as a cautionary and shocking tale. The West End’s urban renewal was among the first in the nation and the Charlestown community got to witness firsthand the effects of urban renewal on their nearby neighbors. Charlestown residents, learning from the West End’s experience, organized quickly and effectively. Groups like the Charlestown Neighborhood Council formed to give residents a voice in the planning process.

At the same time and at a much larger scale, criticism of urban renewal was mounting nationally by the early 1960s. Jane Jacobs’ influential book The Death and Life of Great American Cities had challenged the dominant planning paradigms, and federal policies were beginning to shift. With pressure coming from the grassroots and with the federal government changing its tone, the BRA adjusted its tactics, adopting more community-oriented planning methods under the leadership of figures like Edward Logue.

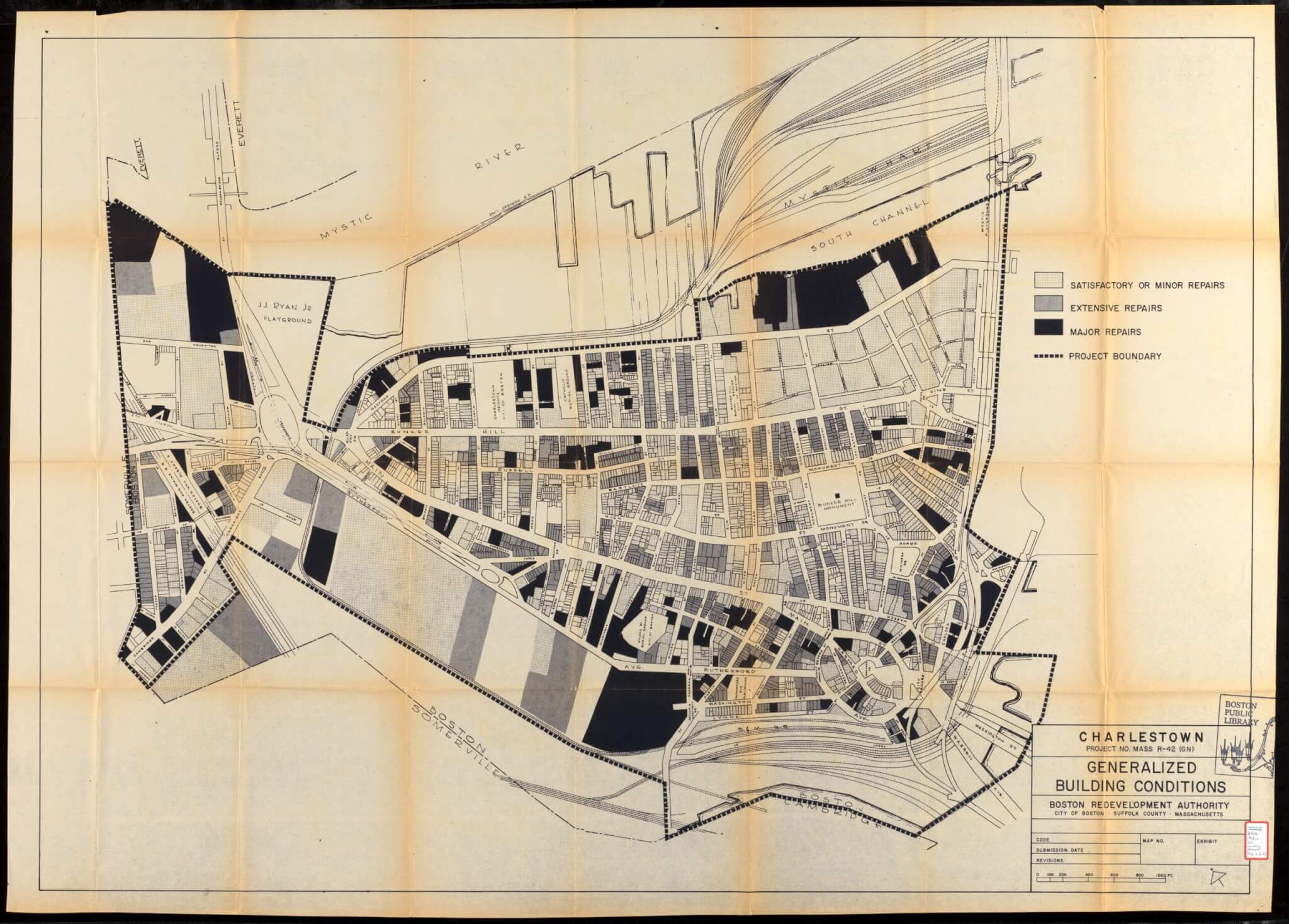

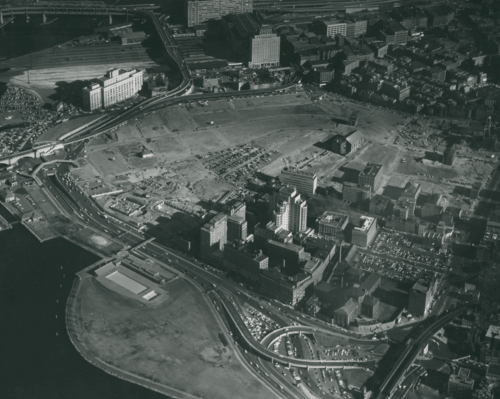

The result was a significantly modified urban renewal plan for Charlestown. The BRA’s initial plan called for 60% of Charlestown’s housing to be demolished. The second, modified plan called for 20% of housing to be demolished, rehabilitating the rest, and building 1,400 new units. While some demolition did occur, particularly in areas like Bunker Hill Street, much of the neighborhood remained intact. The plan became more focused on rehabilitation and selective redevelopment rather than wholesale clearance. The Charlestown renewal also included more affordable housing provisions, with developments like the Bunker Hill Housing Project ensuring that some displaced residents could remain in the neighborhood. Historic preservation became a component of the plan, recognizing Charlestown’s significance in Boston’s history. The plan’s very clear outline of resources available to residents and the provision for things like affordable housing, open space, and community amenities was a vast departure from the West End plan only a few years earlier.

Several crucial differences stand out when comparing these two urban renewal experiences:

- Community Participation: The West End renewal occurred with virtually no meaningful resident input, while Charlestown’s community successfully demanded a seat at the planning table, resulting in a more collaborative process.

- Scale and Approach: The West End saw near-complete demolition, while Charlestown experienced a more selective, preservation-oriented approach that maintained much of the neighborhood’s physical and social fabric.

- Housing Outcomes: The West End was replaced with luxury housing that excluded former residents, while Charlestown’s plan included more provisions for affordable housing and resident retention.

- Timeline and Execution: The West End project moved with remarkable and brutal efficiency from 1958-1960, while Charlestown’s renewal was implemented more gradually throughout the 1960s and 1970s, allowing for course corrections.

- Institutional Learning: The BRA approached Charlestown differently, having learned painful lessons from the West End debacle about the social costs of displacement and the value of existing neighborhoods.

The contrasting approaches to urban renewal in these neighborhoods left distinct legacies that persist today. The West End’s destruction is now widely recognized as a planning disaster that obliterated a functioning community. The neighborhood’s former residents continued to meet for decades after displacement, maintaining “West Ender” identity despite physical dispersal—a testament to the strong community bonds that existed. The area has never regained its former character or diversity.

Charlestown, while changed by urban renewal, retained much of its physical character and community identity. The neighborhood has experienced gentrification in recent decades, but its transformation has been more evolutionary than revolutionary. Many original families and institutions remain, and the area maintains a stronger connection to its historical roots.

Perhaps most significantly, these two cases helped shape Boston’s subsequent approach to development. The West End became a symbol of what to avoid, while Charlestown represented a step toward more inclusive planning. Later Boston initiatives like the Southwest Corridor Project in the South End and Roxbury neighborhoods of Boston incorporated even more community participation, reflecting the lessons learned from these earlier experiences.

Together, these neighborhoods tell a crucial story about the evolution of urban planning—from an expert-driven, clearance-oriented approach toward more participatory methods that value existing urban fabrics. Their contrasting fates continue to inform discussions about how cities should change, who should control that change, and what we risk losing when communities are not meaningfully involved in shaping their own futures.

Article by Daniel Spiess, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Barry Bluestone & Mary Huff Stevenson, The Boston Renaissance: Race, Space, and Economic Change in an American Metropolis (Russell Sage Foundation, 2000); Boston City Planning Department, Comprehensive Planning Section, Charlestown District Study #5, March 14, 1960; Marc Fried, “Grieving for a lost home: Psychological costs of relocation,” in J. Q. Wilson (Ed.), Urban Renewal: The Record and the Controversy, pp. 359-379 (MIT Press, 1966); Bernard J. Frieden and Lynne B. Sagalyn, Downtown, Inc.: How America Rebuilds Cities (MIT Press, 1989); Herbert Gans, The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans (Free Press, 1962); Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Random House, 1961); National Park Service, “Urban Renewal and New Schools Arrive in Charlestown”; J.C. Teaford, “Urban renewal and its aftermath,” Housing Policy Debate, 11 (2000): 443-465.