Walking Competitions

Pedestrianism, or competitive walking, was a nationally popular sport in the 1870s and 1880s. The old West End was captivated by local competitions and news of world record-breaking pedestrians such as Boston’s Frank Hart, the most successful African-American pedestrian in the 1880s.

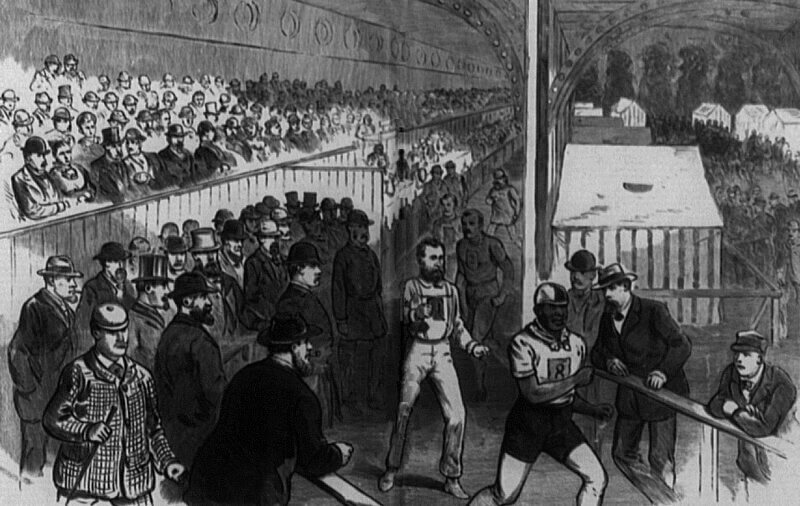

During the nineteenth century, but especially in the 1870s and 1880s, “pedestrianism,” or competitive walking, was a hugely popular sport nationwide. Competitors walked or ran laps for six days at a time on indoor tracks, with cots on the track for pedestrians to sleep for three or four hours. The goal of these competitions was endurance, and the pedestrian with the greatest total miles after six days was awarded first place. The walks traditionally lasted six days because “public amusements” were often prohibited on Sundays in many locales. One competitive pedestrian, Napoleon Campagna, was born in the West End, on Blossom St., in 1827. As a teenager, he became interested in “the pedestrian craze,” as the Boston Globe called it, which was all the rage for West End youth during the 1840s. Campagna, nicknamed “Old Sport” and known for his eccentric tattoos (such as his wife’s name, Jenny, tattooed on both his legs), won small amounts of prize money in pedestrian events. Campagna was known for “a peculiar gait” which made his appearances a comical sight for audiences. Competitive walking was always meant to be an entertaining spectacle, with brass bands, food vendors, and local and state celebrities visiting the races. In the 1880s, Campagna left the West End for California and Chicago, Illinois, and he died of heart disease in an Illinois hospital on April 4, 1906. The Boston Globe released a lengthy obituary of Campagna when he died, describing him as a “celebrated character” with origins in the West End “famed as [a] pedestrian and for tattoo marks.”

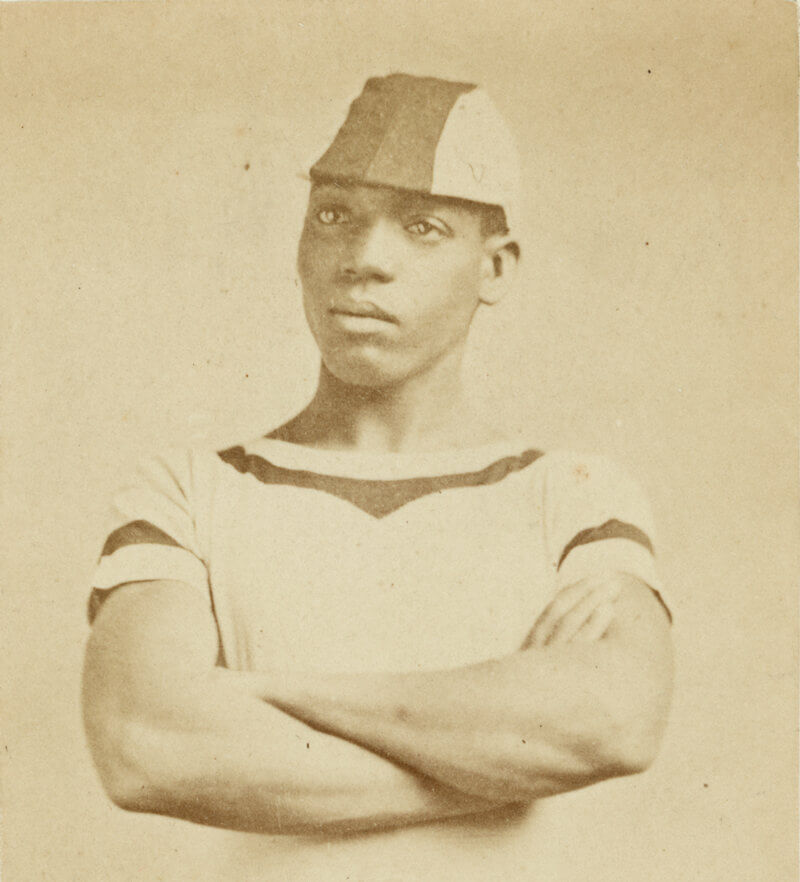

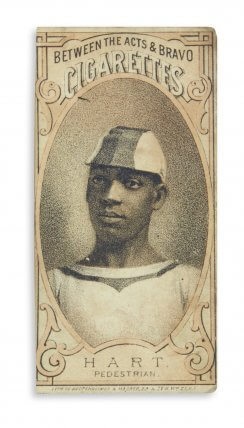

West Enders in the nineteenth century were also keeping up with the news of competitive walking matches at New York’s Madison Square Garden (MSG). One of the most renowned pedestrian competitions at MSG involved Frank Hart, a Black pedestrian born in Haiti in 1858, winning the “O’Leary Belt” on April 10, 1880. The belt was named for Daniel O’Leary, the Irish sports promoter who organized the event and mentored Hart after recognizing his success in Boston walking competitions. Hart immigrated to Boston in the 1870s and worked at a grocery store, but he entered local foot races and succeeded. At the Boston Music Hall in April 1879, Hart won a pedestrian event despite one spectator throwing pepper in his eyes while he led the race. Hart was one of only a few African-American pedestrians, and faced racial prejudice from some spectators. But he believed in his right, and the right of all African Americans in sports, to compete as equals. Hart proceeded to win a six-day race at Madison Square Garden in December 1879 with a total of 540 miles, then a national record. In the next race the following April at MSG, Hart bested seventeen competitors in six days and earned over $21,000 (over $480,000 in today’s dollars). The money came from Hart’s share of ticket sales, a bonus for breaking the six-day race record with 565 miles, and a bet Hart placed on himself. Hart walked against two other African-American competitors, William Pegram, who finished second, and Edward Williams, who finished seventh. All three walked over 500 miles after six days. After Hart won the O’Leary Belt, according to Matthew Algeo, he “was now not just the most celebrated black athlete in the country–he was the most celebrated athlete of any color.”

West Enders in particular were celebrating Hart’s victory as it was happening. During the last hours of the race in 1880, Henry P. Kelly, a “well-known politician and liquor dealer of the West End” (Boston Globe, 1887), sent Hart, his friend, a telegram stating that “The West End is all excitement over your wonderful achievement. Wipe out the English record, and give Boston the greatest pedestrian of the world. It looks like a holiday on Cambridge street.” The popularity of pedestrianism in the West End, bolstered by national trends and the fame of residents like Campagna, gave the neighborhood an affinity for trailblazing walkers from Boston such as Frank Hart. By the late 1880s, baseball overtook pedestrianism in popularity and replaced competitive walking as the national pastime. Hart then changed sports, playing in the National Colored Baseball League (the precursor to the Negro Leagues) for the St. Louis Black Stockings, before he died in 1908.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Atlas Obscura; Running Past; Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Sport by Matthew Algeo; Black Past; NPR; Boston Globe (Campagna: “‘Old Sport’ Is No More,” April 4, 1906, page 9; Kelly: “At His Old Home,” August 23, 1887, page 8)