Jim Campano: Champion of the West End

James “Jim” Campano dedicated his life to preserving the memory of his beloved West End as a protester, journalist, and historian.

James “Jim” Campano (Jimbo in the West End) was born into an Italian-Lithuanian family in 1941. He was the youngest of eight siblings and lived with his family in a second-floor tenement at 32 Poplar Street in the West End of Boston. His father, Frank, who worked as a knife grinder, passed away when Jim was only three years old. Mary, Jim’s mother, now forced to support the large family on her own, took a job in a hospital kitchen. As a child, Jim shined shoes, attended trade school, played in the streets, and enjoyed camps run by the Elizabeth Peabody House. He regularly hung out at the corner of Brighton and Chambers Streets where he and his friends interacted with passersby. In April of 1958, when Jim was seventeen years old, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) commenced with its plans to demolish the historic West End in the name of urban renewal.

Jim witnessed first hand how the designation of “slum,” applied to the West End by Mayor John Hynes and BRA officials, became a self-fulfilling prophecy that engineered the displacement of residents. He recalled, “around 1954 they said that if you fix up your apartment buildings, you might not get your money back because they’re going to end up getting taken. So street cleaning stopped, garbage pickup became sparse and they created an image of a slum.” Like the large majority of West Enders, Jim was strongly opposed to the destruction of his neighborhood and the displacement of his family and friends. He and others proceeded to resist demolition efforts by destroying one of the cranes parked at Haskell’s Garage on the corner of Chambers and Barton Streets. They first poured plaster into the gas tank, and two weeks later Jim threw a Molotov cocktail at the crane. Jim became an activist.

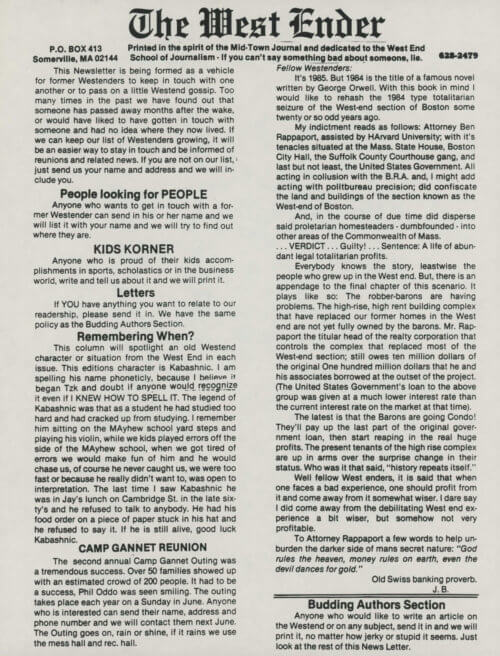

The Campano’s were finally evicted from the West End in 1959, and his mother moved to an apartment in Somerville. Afterwards, Jim briefly joined the Coast Guard, worked in a factory, got married and moved with his wife, Kathleen, into a house in Somerville. Although Jim no longer lived in the West End, he maintained close connections with former residents through reunions, such as one that took place in Sharon in the summer of 1984. That reunion, attended by 125 West Enders, was organized by the Elizabeth Peabody House, which had also moved from the West End to Somerville. The success of the the reunion inspired Jim and another West Ender, Raymond Papa, to produce a newsletter in order to follow up with those who attended and others who were unable to make the event.

Eventually named The West Ender, the newsletter became more of an actual newspaper and Jim enlisted more friends to help with the typing and and printing. By 1987, The West Ender had a circulation of 1,800, and later reached a peak of almost 4,500 mail orders. Jim offered the newspaper to readers at no cost, though he did encourage donations to cover mailing. Each issue of The West Ender was filled with the memories and reflections of former West End residents. Here they were able to maintain, what Jim described as the “neighborhood of the mind,” in the absence of the physical West End.

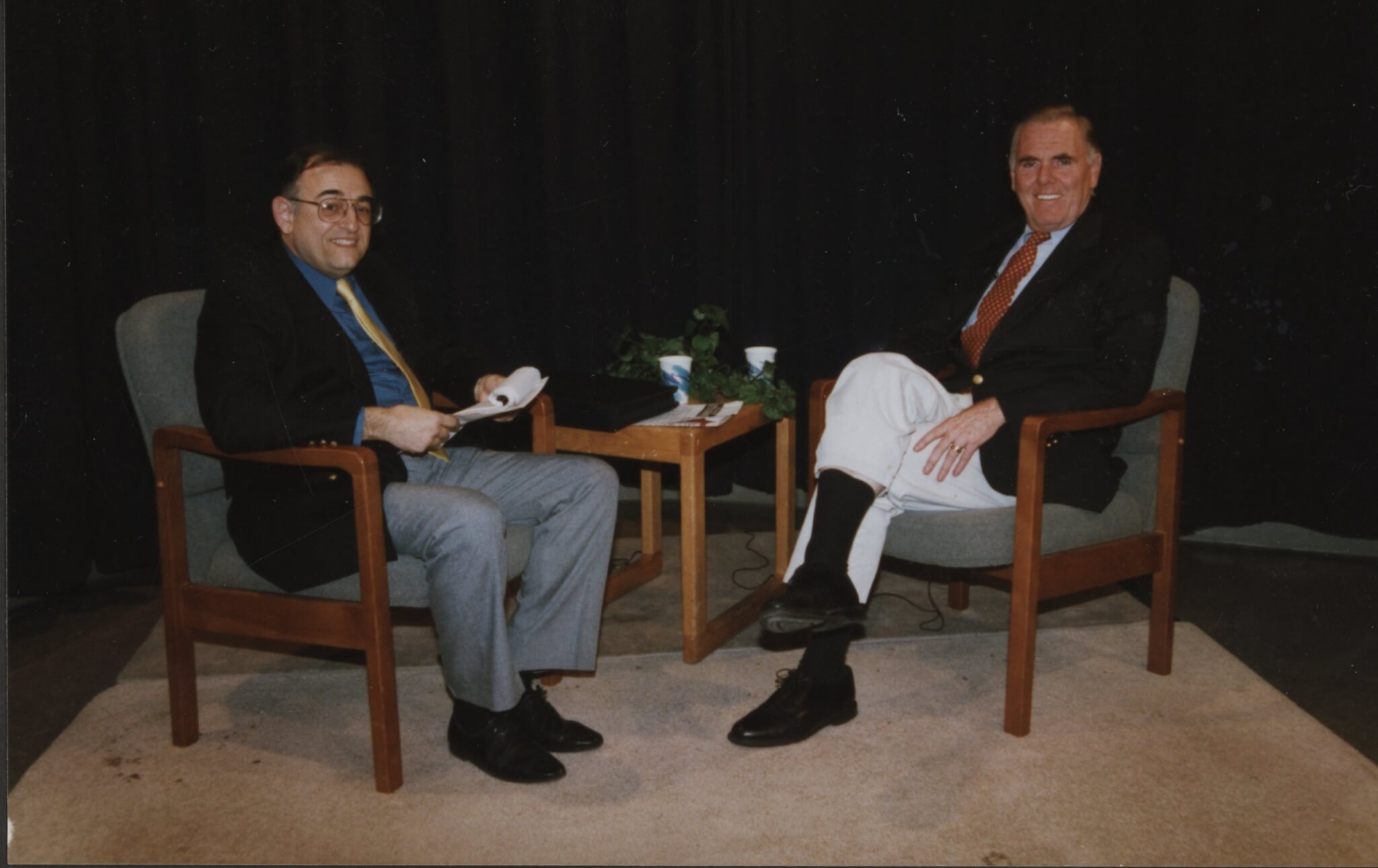

Jim supplemented the printed edition of The West Ender with a community television show, The West Ender Video Newsletter that he and others hosted and aired once a month on Somerville’s public access station. As someone who publicly represented and advocated for the West End’s history, Jim was often sought out as a speaker by local historical societies and colleges such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). For Jim, writing and speaking about the destruction of his beloved neighborhood was both cathartic and productive. He told The Wall Street Journal, “I got over my hate by writing it out. Then I realized that people were reading me.” Some of Jim’s readers included government officials, as well as Jane Jacobs, the urbanist who famously opposed urban renewal and advocated for the preservation of vibrant, high-density city spaces.

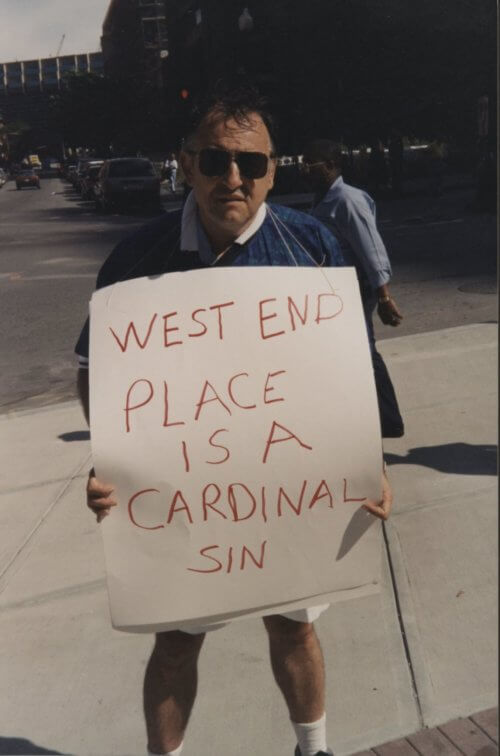

In 1992, as head of the Old West End Housing Corporation (OWEHC), Jim helped negotiate the development of West End Place, a mixed-income condominium set to be built on an unused lot at the corner of Staniford Street and Lomasney Way. The lot was reclaimed by the BRA in 1992 after a legal battle with the former owner, Charles River Park Inc., developer of the luxury apartment towers that replaced the West End’s tenements. Jim and OWEHC fought for prioritized housing for former West Enders in the new development, but lost. They did, however, win as a concession from Keen Development Corporation, a space for a museum dedicated to the West End’s history.

Jim became the first president of The West End Museum when it opened its doors in June of 2004 at 150 Staniford Street. Free of charge to visitors, The West End Museum was originally open four days a week and gave the public the opportunity to pore through old records and photographs, and to watch “The Lost Neighborhood,” an 1962 ABC program about the West End’s demise. The West End Museum had another grand opening in October 2007, with a new, permanent exhibit called “The Last Tenement,” produced by The Bostonian Society in 1992.

In his later years, Jim suffered through some health issues and the loss of his wife, Kathleen. Though he stepped away from the day to day running of the Museum in 2011, he remained a member of its board and continued to publish The West Ender into 2023. At an event at The West End Museum, after BRA director Brian Golden offered a formal apology for the agency’s destruction of the West End, Jim acknowledged that “although the destruction happened decades ago, the scars still remain. We haven’t forgotten.” On Saturday May 20, 2023, the West End lost its greatest champion when Jim passed away in his old neighborhood at the age of 82. His legacy of work and his fighting spirit will forever inspire those who believe that a community is worth saving.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Boston Phoenix; Patch; The West End Museum; SAH Archipedia; ProQuest (Peter Anderson, “West End Story,” Boston Globe, May 24, 1987; Robyn Jones, “A Museum’s Tale,” Boston Globe, June 20, 2004; Michael Kenney, “The museum feels their pain,” Boston Globe, October 21, 2007; Jon Chesto, “BRA director offers formal apology for West End’s demolition,” Boston Globe, September 28, 2015; Barry Newman, “Lonely Causes – West End Story,” The Wall Street Journal, August 23, 2000)

Mel King