Population and Housing Trends in the Post-Renewal West End

Urban renewal is a process that aims to revitalize and transform urban areas to meet changing societal needs, but it can also have far-reaching consequences, particularly in terms of population and housing dynamics.

In the 1950’s and 1960’s, urban renewal initiatives swept across the United States, seeking to address perceived issues of blight and overcrowding in cities. On April 11, 1953, Mayor John Hynes officially announced the West End Project, promising that redevelopment would be beneficial to the neighborhood and the city as a whole. Years before he made his address, Boston’s City Planning Department had determined what the project was meant to achieve.

The West End Project Preliminary Report of 1950 stated many alleged problems with the West End:

- The neighborhood was overcrowded [yet on the same page it was noted its population had been declining for decades]

- Residential buildings were dilapidated

- Schools, community services, and play spaces were “far below a desirable level”

The same report also promised several remedies:

- All people living in substandard housing [80% of the housing stock according to the report] would be “rehoused at prices they can afford to pay”

- The rebuilding of the substandard building would have a beneficial effect on the remaining parts of the neighborhood

- The project would be completed within three to four years

What the West End got instead were high-rise, high-income residential towers along the Charles River which most current residents could not afford.

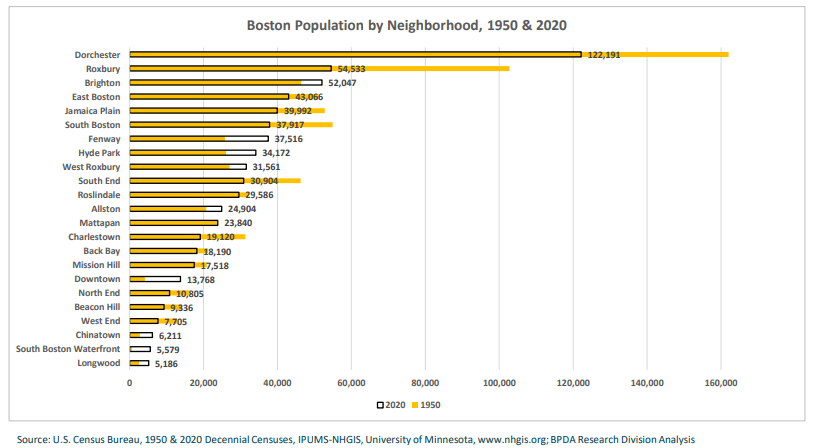

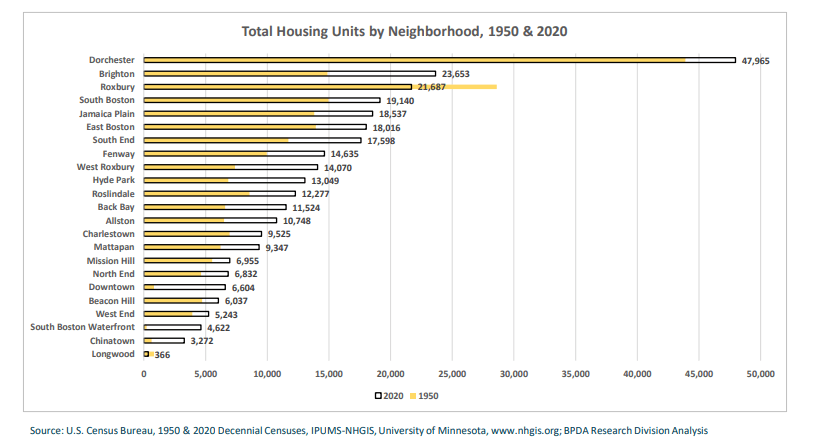

Recent studies by the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) shed light on the significant impact urban renewal projects have had on population and housing. Urban renewal efforts in the West End led to the widespread displacement of the existing population. In the name of progress, entire blocks were demolished, displacing thousands of mostly low to moderate income families. Families that had lived in the West End for generations found themselves uprooted and scattered throughout the city and beyond. The project accelerated years of existing population decline in the West End. From a high of over 22,000 people in 1910, the neighborhood bottomed out at a little over 4,000 residents by 1980. As of the 2020 census, the neighborhood population was still under 8,000.

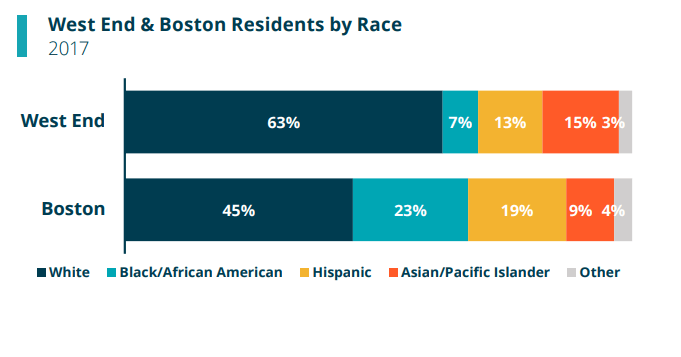

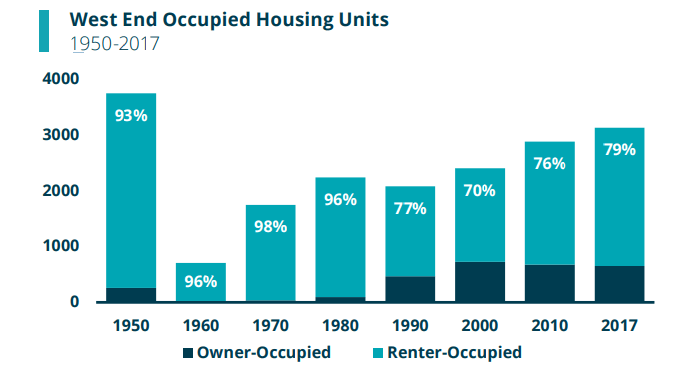

Simultaneously, as post-urban renewal population numbers changed, the demographic makeup of the West End also underwent notable shifts. The influx of higher-income residents and professionals, coupled with the construction of high-rise apartment buildings and luxury condominiums, transformed the area into a more affluent neighborhood. Between 1950 and 2020, the percentage of U.S. vs. foreign-born residents stayed almost exactly the same (74% vs 26%), but the racial and ethnic makeup of the neighborhood changed significantly. In 1950, 98.8% of West End residents were white, while that number fell to under two-thirds (63%) by 2020. Though Boston lags behind the rest of the US in home ownership, and housing affordability is consistently rated a top issue, the rate of area residents purchasing their homes has tripled since 1950.

Looking back at the original West End Project Preliminary Report, one can see that over time some problems and solutions were indeed addressed: overcrowding was alleviated and the quality of the housing stock was improved. Home ownership has also increased and the neighborhood has become more racially diverse. But the benefits cannot ignore the immense harms: forced population removal; complete destruction of the neighborhood’s character; and home ownership is mostly available only to those in upper income levels.

In recent years, there have been efforts to revitalize the West End and restore some of its lost character. Urban planning initiatives now focus on creating a more balanced and inclusive community. Affordable housing projects and community engagement programs have been implemented to counteract the effects of gentrification and promote socioeconomic diversity. The changing population dynamics of the West End since urban renewal have resulted in a more complex community with a new set of challenges. While the neighborhood may never fully recapture its pre-renewal character, continued revitalization efforts are striving to create a diverse and inclusive environment that acknowledges the neighborhood’s historical significance.

Article by Daniel Spiess, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: O’Connor, Thomas H., Building a New Boston: Politics and Urban Renewal, Northern University Press, 1993. ISBN 1-55553-161-X; Simonian, Kane. Urban Redevelopment Division, Boston Housing Authority. The West End Project Report: A Redevelopment Study (https://archive.org). Boston, March 1953.; “RENEWAL IN BOSTON: GOOD AND BAD”,(https://www.nytimes.com/1964/04/19/archives/renewal-in-boston-good-and-bad.html). New York Times. 19 April 1964.; Historical Trends in Boston Neighborhoods Since 1950. BPDA. June 2023 (https://www.bostonplans.org). Accessed August 2, 2023.; Historical Boston in Context. BPDA, March 2023 (https://www.bostonplans.org). Accessed August 8, 2023.;BPDA: West End. Produced by the Boston Planning & Development Agency Research Division, March 2019 (https://www.bostonplans.org).