Repurposed Churches and Schools in the South End

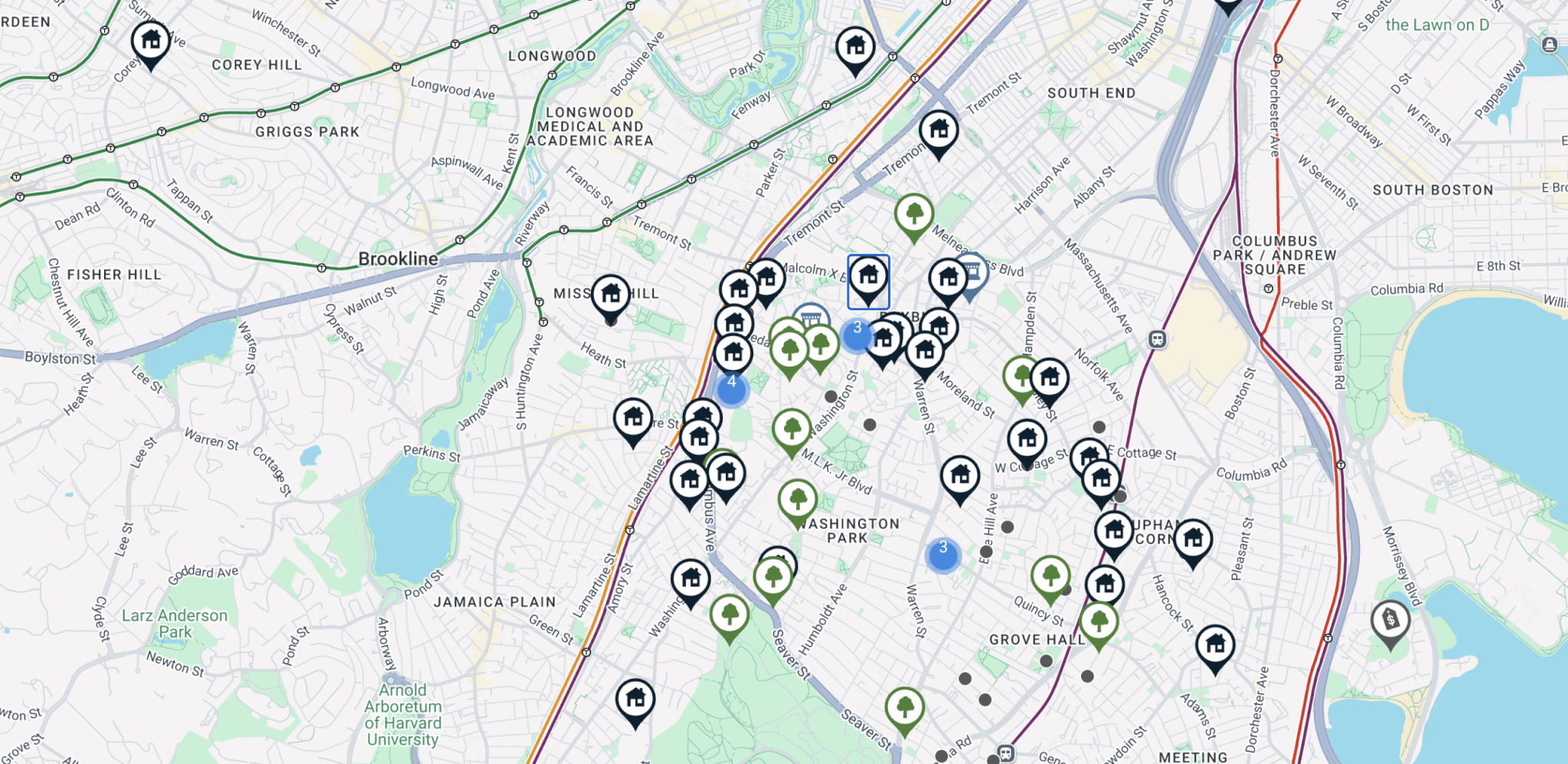

As neighborhood demographics have changed in the South End, public buildings and the communities they once served have relocated. Those churches and schools have mostly been preserved in the form of condominiums. However, these units are often high priced and inaccessible to most people. This article considers the repurposing of South End public buildings into housing as a case study on balancing preservation of the past and the housing needs of the present.

At a time when housing, especially affordable housing, is in short supply across Boston, urban planners must weigh their options. There is a need for housing, but as has always been the problem in Boston, not many places to put it. This often means building upwards. But there is also a question of neighborhood character and community to consider. What, planners must ask, is more important: providing housing or preserving the past? This article considers attempts in the South End to address the housing problem without destroying the character people remember about the neighborhood.

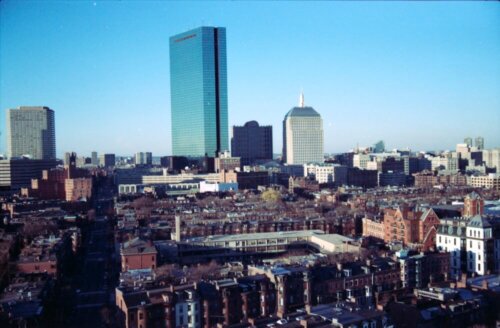

Walking its streets, it seems fitting that in 1973, the South End was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was “the largest urban Victorian neighborhood in the country” and, in 1983, was named a Boston Landmark District. The South End’s gentrification and changing demographics have had an impact on the religious and public buildings in the neighborhood. As the population has changed, the buildings used by previous generations have begun to be transformed and repurposed into residential spaces.

Institutions who own property in the South End must grapple with a complex dilemma. Should they honor their South End heritage amidst the changes and keep buildings as they are? Or should they seize an opportunity to capitalize on rising property values and relocate for the next generations? Finally, what will the impact of these choices be on their communities who are affected by gentrification?

Built in the 1850s and dedicated in 1861, the Catholic Church of Immaculate Conception at 771 Harrison Avenue was designed with a renaissance revival style. The church added an addition in the 1960s. This was the original home for Boston College, established in 1863. The early program lasted seven years and combined high school and college. The building adjacent to the church at 21 Father Francis Gilday Street was part of the campus. Boston College High School and College shared the site until 1913, when the college moved to Chestnut Hill. The two institutions were legally separated in 1927. By 1950, Boston College High outgrew the South End and moved to a new location on Columbia Point. Dwindling attendance, financial shortfalls, and high maintenance costs forced the church to close in 2007. Both 21 Father Francis Gilday Street and 771 Harrison Avenue became condos in 2006 and 2020 respectively. Today the buildings are Penmark Condominium and Cosmopolitan Condominium. They both feature luxury units.

In 1968, the New Hope Baptist Church moved to Tremont and West Concord Streets to serve a growing Black Baptist congregation. They occupied a 1863 building originally used by the Tremont Street Methodist Episcopal Church. By 2012 the Rev. Kenneth Sims found the congregation spending upwards of $250,000 to maintain the building. Later that year, the building was sold to developers for $3.6 million, while New Hope moved to Hyde Park via a $1.8 million purchase. The 740 Tremont Street Condominiums opened in 2015 and included 6 townhouse-style units.

The building that housed the Concord Baptist Church, at the corner of West Brookline Street and Warren Avenue was completed in 1869. The church was founded by Black residents who had moved north during the Great Migration. They started in West Roxbury in 1916, and, with a growing congregation, moved to the South End in 1946. The church thrived there over the next 50 years, but parking challenges forced the church to reassess their needs for the future. By 2008, the church sold the building to developers. After years of fundraising and seeking a new location, a 22,000 square foot former Synagogue in Milton was chosen as the home for the Church. The Luxury Residences at 201 West Brookline Street opened in 2018.

Another Church building completed in 1869 was the Clarendon Street Baptist Church, at 2 Clarendon Street. Gutted by fire in 1982, it was subsequently developed into 2 Clarendon Square Condominiums in 1987.

The Bancroft and Rice School on Appleton Street at Dartmouth Street were also completed in 1869. Bancroft and Rice was part of the Boston Public School System. However, it closed permanently in 1981. The school was one of the many victims of Boston’s school desegregation turmoil of the 1970s. The building was converted into the Dartmouth Square Condominiums in the mid 1980’s. A two bedroom unit in this building sold in December of 2025 for $1.3 million.

The Ebenezer Baptist Church at 157 West Springfield Street dated back to 1871. According to the church’s history, founding members of this long-standing congregation were 66 formerly enslaved people who came north on a ship in 1847. It has remained a Black Baptist church for decades. The Ebenezer faced an aging building requiring significant maintenance amid drastically changing demographics. In 2022, the church purchased property 21 miles away in Abington for $1.6 million. It sold the West Springfield site for development for $4.7 million. Construction to repurpose the Church into residences is in progress as of December 2025. While the condos are sure to be luxury level units, the architects who are working on the project have promised to preserve the building’s design. Additionally, a memorial to the civil rights and Black heritage of the church has been included in plans.

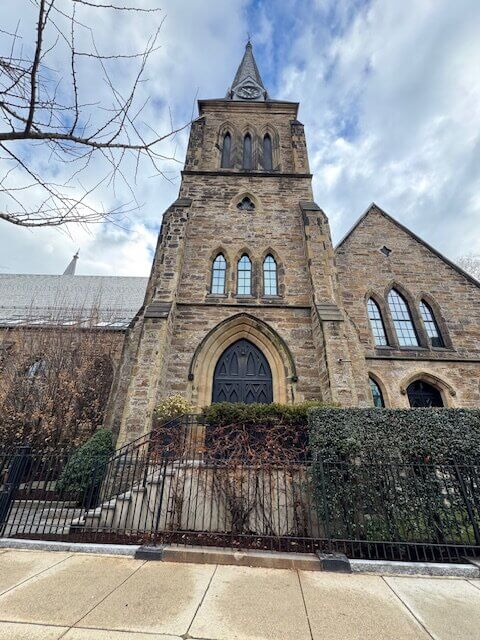

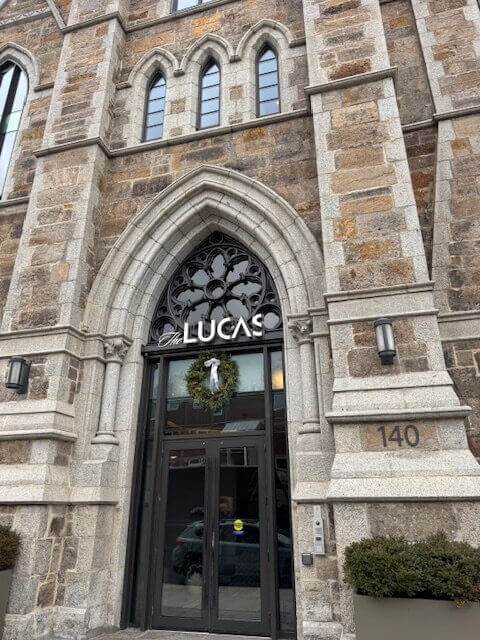

The oldest church of all was the Holy Trinity German Catholic Church at 140 Shawmut Avenue, opened in 1844. Thanks to an ever-growing congregation, a second, larger church was subsequently built in the 1870’s. In 2008, despite four years of efforts by the parishioners to keep it open, the Archdiocese of Boston shut down Holy Trinity. It was sold to a developer in 2014 for $ 7 million. After 164 years, the Holy Trinity exists only as a hollowed-out shell. The majestic stone facade now hosts The Lucas with 33 luxury condos rising in glass from the building. Sales opened in 2016.

These stories are certainly not exclusive to the South End. Rising income inequality has often triggered gentrification, as does changing demographics. Boston’s urban renewal in the 1950’s and 60’s also played an oversized role, as did the attempt at desegregating schools. The destruction and subsequent attempts at rebuilding wreaked havoc. Boston’s Catholic population felt urban renewal closing in when, in 1961, Holy Trinity was a few short blocks from the recently razed New York Streets. At the same time, plans were in place to close its religious school with the impending urban renewal project in adjacent Castle Square.

Black South Enders were first pushed towards the neighborhood with the prospect of home ownership. This led to white flight and the neighborhoods became more homogenous. As gentrification increased in the South End, the Black population plummeted as white residents returned from the suburbs. Many Black Bostonians, like the baptist churches that once dotted the South End, have moved farther from downtown.

In addition to the issues with neighborhood affordability, sociologist Robert Putnam’s landmark research in “Bowling Alone” illustrated how civic engagement, including in religious institutions, has been in steady decline in America since 1950. Tying all these factors together supported a most unfortunate result. Churches and the Bancroft and Rice School in the South End simply couldn’t sustain themselves or their congregations. There may be some solace that the buildings have been salvaged, and repurposed to a new use, albeit not to everyone’s satisfaction. Few of the units in these historic churches are affordable. The buildings have been preserved, but not for people who once worshipped there but have since been priced out of the area.

Most of the buildings referenced, with the exception of 140 Shawmut Avenue, stand amongst the South End’s 19th century Victorian architecture. The city as a whole no doubt still benefits from the preservation of such beautiful architecture. Only now instead of congregations of working class Bostonians inside their arched ceilings, these former churches boast in-unit laundry and gourmet kitchens. It was bittersweet for the churches who were priced out of the South End, even for those that saw a large profit in selling and relocating to larger buildings. It may have stabilized and in some cases enhanced their future. But it came with a cost. This begs the question: did the churches honor their heritage by selling to developers? And can they be blamed if they used their property to relocate to better serve their communities? The public beauty is now inaccessibly private, yet the buildings still stand.

Article by Irwin T. Levy, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Mariya Amrayeva, Gaia De Simoni, Heather Salz, and Andrea Wang, “Holy Condos: Parishioners keep faith after their churches in the South End were turned into condos,” (BU Journalism, Shorthand Stories); Boston Redevelopment Authority, “Old Boston College High School, 761 Harrison Avenue, South End,” (Internet Archive, 1990); Campion and Company, “The Penmark”; Coastal Neighborhoods, “Dartmouth Square”; Compass, “Two Clarendon Square (aka The Church at 2 Clarendon); Concord Baptist Church, “Concord History”; Mary Cunningham, “These U.S. cities have seen the biggest rent increases since 2020” (Money Watch CBS News, December 4, 2025); Ebenezer Baptist Church, “Our Story”; Adam Gaffin, “Condo owners in converted South End church raise holy hell over problems they say include shoddy construction and AC that failed repeatedly over the summer” (Universal Hub, October 29, 2025); Global Boston, “The South End” (Boston College, Department of History); Yawan Miller, “Boston blacks made exodus to Roxbury: Small Beacon Hill community moved to south neighborhoods” (The Bay State Banner, February 9, 2018); New Hope Baptist Church, “Church History”; Patrick E. O’Connor, “Immaculate Conception closes in the South End,” (The Pilot, August 10, 2007; Sarkis Team, “The Cosmopolitan at 771 Harrison Ave”; Rode Architects, “157 W Springfield St. Courageous Contrast: Contemporary Future Rises from a Ric Past”; Robert J. Sauer, Holy Trinity German Catholic Church of Boston: A Way of Life, (Boston: Holy Trinity German Parish, 1994); Meghan Smith, “Keeping private rentals cheaper is key to Mass. housing crisis, new report says” (GBH Boston, December 17, 2025); Kate Sullivan, “Livin’ on a Prayer,” (Columbus & Over Group, December 2016); Tiana Woodard, “Some Black churches are leaving Boston, citing changing neighborhoods, higher costs,” (Boston Globe, January 17, 2024).