The Inner Belt: The Highway Massachusetts Didn't Build

Modern Boston has been shaped by its finished highway projects: the Central Artery, the Southeast Expressway, the Big Dig. But just as key to the character of the city today is a highway that was NOT built: the Inner Belt. This article explores how people fought to be put before highways.

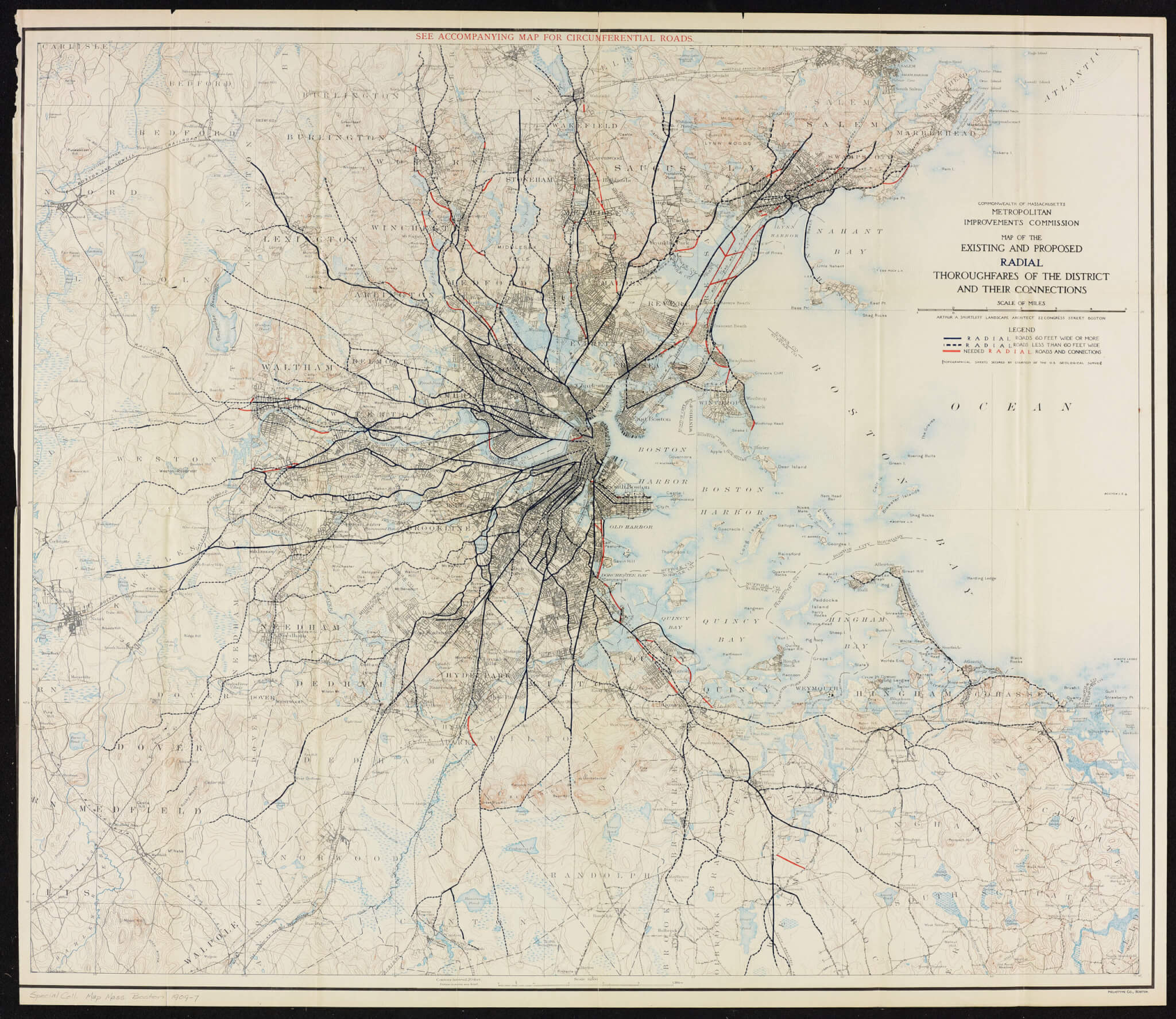

As early as 1910, Massachusetts officials proposed a system of radial highways with arteries to connect them. In the first half of the 20th century, tunnels, bridges, and highways carved their way through and under Boston. The Sumner Tunnel opened in 1934, the Tobin Bridge in 1950, and the Southeast Expressway in 1958. Highway projects were considered progress. Starting in the 1960s, however, an anti-highway movement pushed back against wide scale highway building. The city of Boston came to be defined by roads not completed, including the Inner Belt.

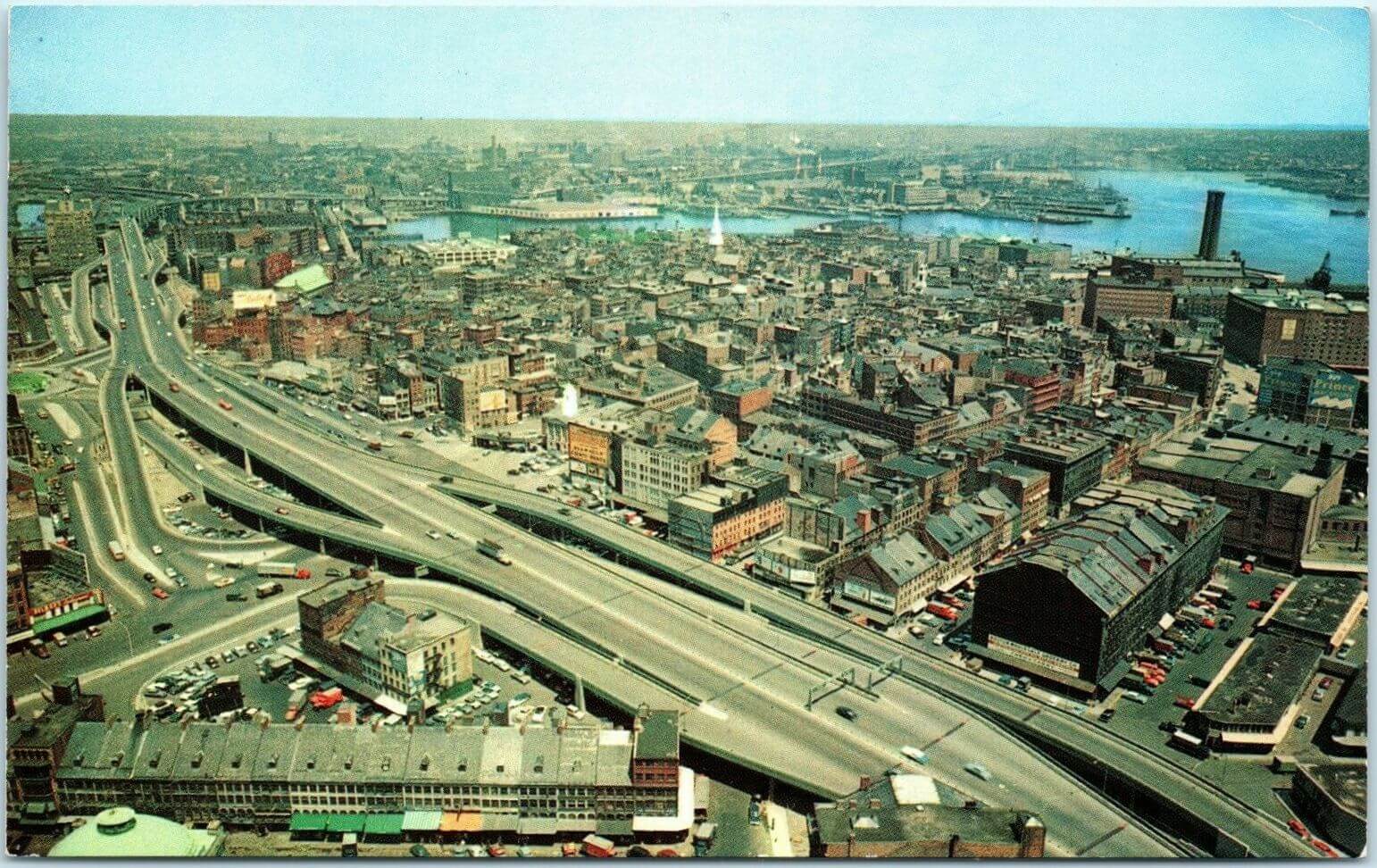

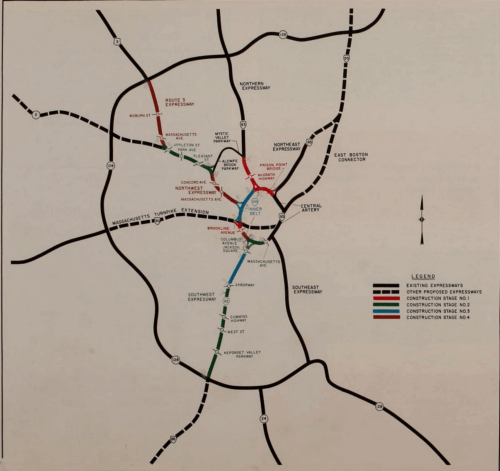

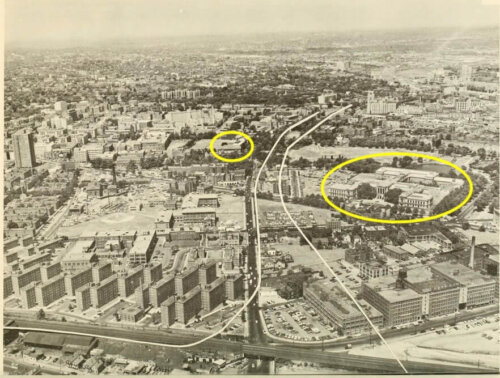

The state issued a “Master Highway Plan” for highways in 1948. The plan called for two loops around the city (outer and inner), with several expressways extending into the urban center. This was known as a spoke and wheel design. The outer wheel became Route 128, finished in 1960. It wrapped around the city on the north, west, and south sides, about 10 miles from downtown. The proposed inner loop included the Central Artery on the east side. The six-lane Central Artery cut through a swath of the North End during the 1950s and opened up to elevated traffic through the city. The rest of the inner loop remained unbuilt for later planners to tackle.

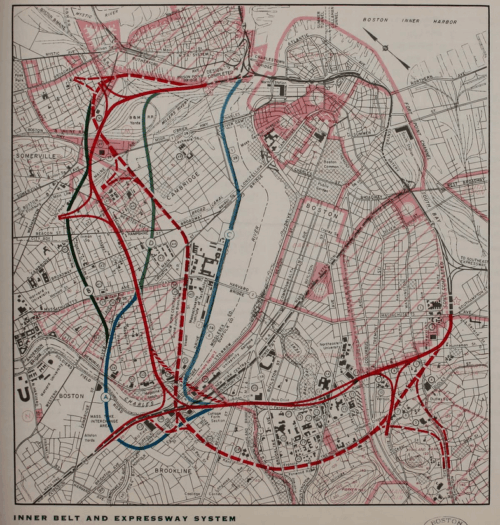

In 1962, the Commonwealth issued a report called The Inner Belt and Expressway System. The planned Belt was called Interstate 695 and designed to be 10 miles long, 8 lanes wide, and mostly elevated. It would run from Charlestown through Somerville, Cambridge, and Brookline. It would then dive back into Boston through the Fenway, Roxbury, and the South End. The Belt would connect with the Central Artery to complete the loop. It would also link up with the radial expressways: Southeast, Southwest (not built), Western (became the Mass. Pike), Northwest (became Route 2), Northern (became I-93), and Northeast (became a version of Route 1). The reasons the Southwest Expressway was not built would be tied closely to the story of the Inner Belt.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, construction of the Inner Belt and the Southwest Expressway seemed inevitable. Institutional support was broad. To revitalize downtown Boston, Mayors John Hynes (1950–1960) and John Collins (1960–1968) pushed the two projects. The Boston Chamber of Commerce, organized labor, and Boston newspapers also supported them. Both projects would have been Interstate highways. Thus the federal government would pay for 90 percent of construction costs and the state only 10 percent. State officials were eager to take advantage. A Boston Globe article in May 1962 called the Inner Belt “by far the most important road ever planned for metropolitan Boston.” Ed Logue, director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, said that if the highways weren’t built, the “core business district would be hollow.”

Support from the public was weaker. When public meetings on the Belt and SW Expressway began in 1960, citizens had reason to be suspicious of government projects. The devastating urban renewal projects in the West End were widely known. In addition, several new highways had taken houses and left scars in the middle of the city. The Central Artery took property along its path and separated the North End from downtown. The Massachusetts Turnpike Extension had also destroyed many homes in Brighton.

From town to town, people learned about the presumed impact of the Inner Belt. Strongest opposition to the Belt began in Cambridge. Clearing for the Belt would have destroyed 5,000 homes, of which 1,300 would have been in Cambridge. This was 5 percent of Cambridge homes, nearly all of it belonging to the working class. Cambridge businesses employing 4,000 people would have had to close. Meeting with state officials in a Cambridge high school auditorium in May 1960, 2,500 residents chanted, “We don’t want a road. We want our homes.”

As for the Expressway, its eight lanes would have run through Hyde Park, Jamaica Plain, Roxbury, and the South End. Roxbury would have felt the impact particularly hard. The neighborhood was slated to lose 5,000 homes. The Belt and Expressway were supposed to intersect in a five-story interchange of loops and ramps near Roxbury Crossing. The Black Panther Party and the Black United Front, an umbrella organization headed by Chuck Turner and other community organizers, led the opposition. In the course of the 1960s, anti-highway activism increased in all the towns on the Belt and Southwest Expressway planned routes.

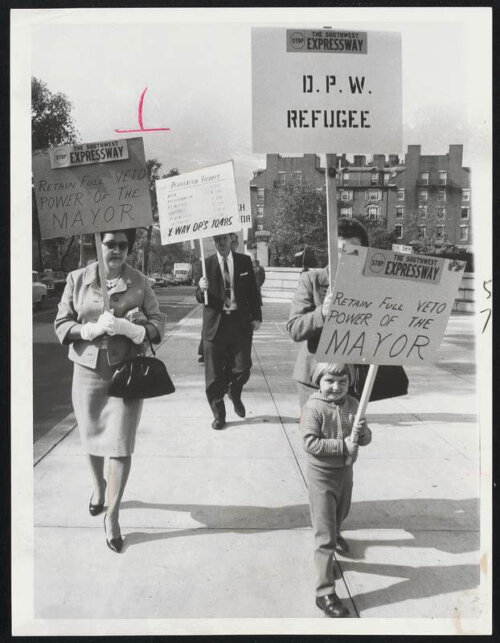

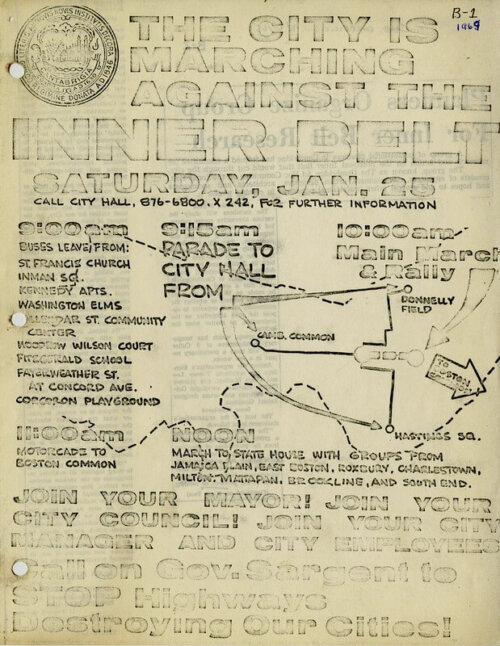

Anti-highway organizers first assumed the highways would happen despite their opposition. So, they focused on changing routes or designs to reduce the damage to neighborhoods. It did not seem possible to halt the Belt entirely. Then in 1968, the Greater Boston Committee on the Transportation Crisis (GBC) brought together activists fighting both highways. This coalition included liberal white people, civil rights organizers, Black Power activists, union workers, Native American rights activists, and women’s groups. The GBC came to believe that if people united, the proposed highways might actually be stopped. In 1969 the GBC demanded a moratorium on all highway construction inside Route 128. This was a revolutionary challenge to state highway policy.

On January 25, 1969, the factions and neighborhoods came together in the People Before Highways Day, a rally at the Massachusetts State House. The new governor, Francis Sargent, watched from his office. Sargent had been Commissioner of Public Works in the mid-1960s and had overseen plans for highway routes. Ironically, he now seemed ready to listen to the people. Sargent came out of the State House and addressed the crowd: “If we ever build highways, we must build them with a heart.” But work was already taking place: Houses were being taken. Land was being cleared. By summer 1969, about 300 homes had been taken in Cambridge and Somerville for the Belt. More than 1,200 homes had already been seized along the corridor for the Southwest Expressway.

Sargent appointed a task force to review all state highway and transportation plans. This included anti-highways activists such as Chuck Turner. The committee’s report in early 1970 criticized both the likely effects of building the highways and the planning process, including not obtaining professional traffic figures. The task force said that “interstate highways within Route 128 will be built as planned, it appears, not because they are the best public investment –– or even the best highway investment –– for the money. They will be built solely because they involve ten cent dollars from the state standpoint.” This was not surprising, as no state government in the United States before 1970 had refused federal highway money.

The report called for work on the Inner Belt and Southwest Expressway to stop, pending a comprehensive review of the region’s transportation. On February 11, 1970, Sargent gave a ten-minute television address. He ordered a freeze on new construction, land clearing, and property taking, as well as a thorough new study of highway plans. “Nearly everyone was sure highways were the only answer to transportation problems for years to come. But we were wrong.” He pushed for a new U.S. policy to allow greater autonomy for states in using highway funds.

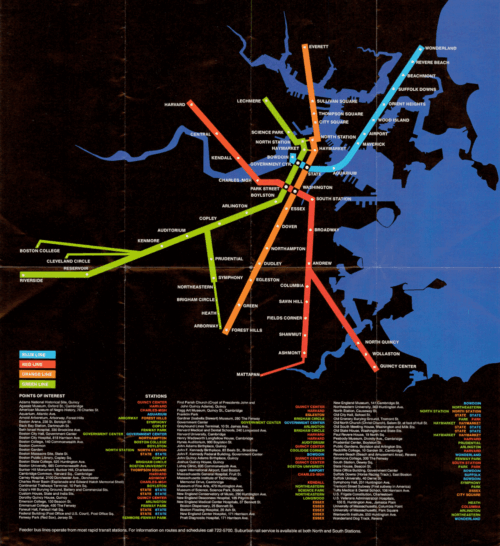

Soon after, the U.S. Department of Transportation funded a two-year study of the region’s entire transportation system. This included not only highways but also local roads, bridges, tunnels, buses, and subways. On November 30, 1972, Sargent cancelled the Inner Belt and Southwest Expressway for good. The Commonwealth gave up 25 miles of highway and related federal funds. It was the largest cancelled highway project in the country to that time. In a huge shift in policy, Massachusetts became the first state to take advantage of a provision in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973 by using highway funds for mass transit instead. Funds were reallocated for the extension of the Red Line to Alewife and eventually the relocation of the Orange Line along the former site of the Southwest Expressway, now called the Southwest Corridor.

Many signs of the halted Inner Belt and Southwest Expressway remain today. The stub of a ramp from I-93 in Somerville goes nowhere. A cleared area for the Belt in Roxbury became Melnea Cass Boulevard. In Canton, I-95 was supposed to continue north on the Southwest Expressway. Instead it merges into an awkward one-lane, tight loop so that it can join with Route 128 around the city. The fight against the Inner Belt and Southwest Expressway changed the way Boston – both city officials and residents – thought about highways and urban planning. No longer would the Commonwealth build highways simply because they could. Instead, they would consider what was best for the people who would be most affected. In years to come, this people-focused policy came to the forefront during the planning for Boston’s Big Dig.

Article by Christina Horn, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Boston Globe (May 20, 1962; Jan. 25, 2019); Karilyn Crockett, People Before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and A New Movement (University of Massachusetts Press, 2018); Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Inner Belt and Expressway System: Boston Metropolitan Area, 1962; Commonwealth of Massachusetts, The Master Highway Plan for the Boston Metropolitan Area, 1948; Anthony Flint, “Boston’s Highway That Went Nowhere: Lessons from the Inner Belt Fight, 40 Years Later,” bloomberg.com, May 1, 2012; History Cambridge, “Inner Belt Hub” ; Alan Lupo, Frank Colcord, and Edmund P. Fowler, Rites of Way: The Politics of Transportation in Boston and the U.S. City (Little, Brown, 1971); Massachusetts Department of Public Works, “Preliminary Relocation Survey: Roxbury District of the City of Boston,” 1965; Thomas H. O’Connor, Building a New Boston: Politics and Urban Renewal, 1950 to 1970 (Northeastern University Press, 1993); Nancy S. Seasholes, ed., The Atlas of Boston History (University of Chicago Press, 2019); Jim Vrabel, A People’s History of the New Boston (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014); WGBH News podcast, The Big Dig, 2023, episode 1, “We Were Wrong.”