Abbott Lowell Cummings and the “Vanishing West End”

Abbott Lowell Cummings, once the leading expert on early New England architecture, spoke out and took action in response to the indiscriminate clearance of the West End during the urban renewal period.

Abbott Lowell Cummings was born in St. Albans, Vermont on March 14, 1923. Growing up in Connecticut with his grandmother on his father’s side, Cummings cultivated a strong interest in New England’s architectural past at an early age. When Cummings was fifteen years old, his grandmother gave him a membership to the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (founded by William Sumner Appleton, Jr. in Boston in 1910). The mission of SPNEA (presently Historic New England) since its founding has been to “rescue and restore”’ historically significant buildings in New England. Cummings studied art history and American architectural history at Oberlin College, receiving his BA in 1945 and MA in 1946, then completed his PhD at The Ohio State University in 1950. Between 1948 and 1951, Cummings taught courses at Antioch College in Ohio, and during that time he studied the architectural style of Asher Benjamin by analyzing his pattern books. In 1806, Benjamin designed the Old West Church on 131 Cambridge Street in the West End, which replaced the original church built in 1737 on account of inadequate space and the need for major physical repairs. The West Church was Benjamin’s first commissioned work in Boston, and Nancy Voye argues that this West End landmark is “central to a study of Asher Benjamin as a stage in his architectural career in Boston.” After studying Asher Benjamin’s work, and joining the staff of SPNEA in 1955, Cummings became the leading authority on “First Period” (seventeenth and early-eighteenth century) architecture in New England when he wrote The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725 (published in 1979).

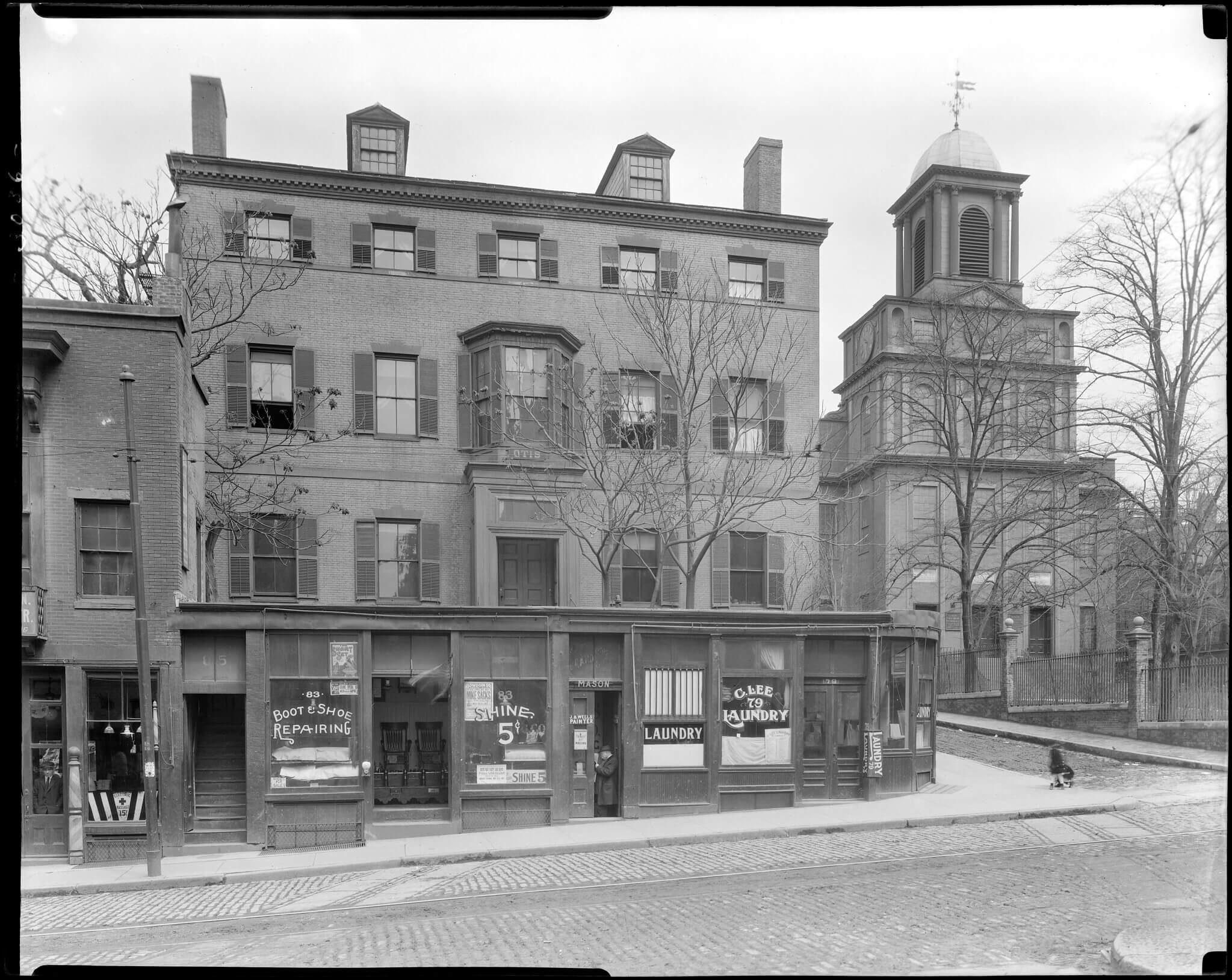

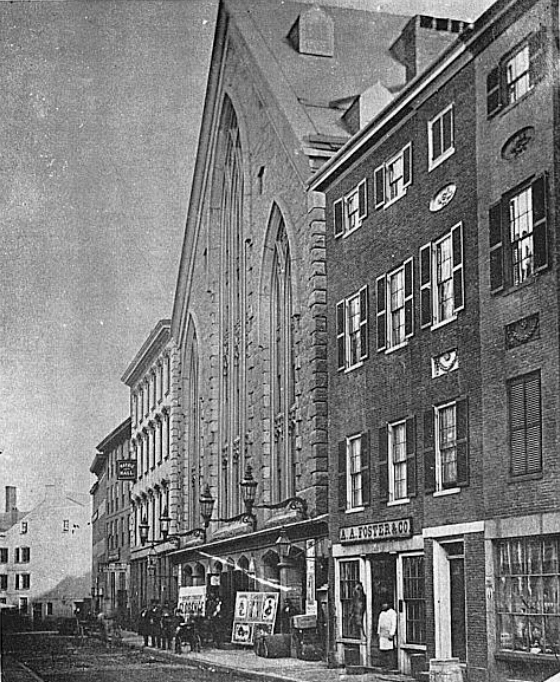

Prior to writing Framed Houses, Cummings focused his appreciation of historic New England architecture towards the historic buildings of the West End, specifically those buildings torn down by urban renewal. Cummings wrote “Charles Bulfinch and Boston’s Vanishing West End” in the October-December 1961 issue of Old-Time New England, the journal published by SPNEA. Urban renewal razed 50 acres of the historic West End, starting in 1958; Cummings addressed the land clearances taking place between 1960 and 1961. Cummings argued that indiscriminate urban renewal in the West End was a serious offense against the architectural and historical integrity of Boston. He began the essay arguing that urban renewal in the West End “created a devastation here unmatched since that of the fire of 1872 in the downtown area.” The city preserved Asher Benjamin’s West Church and Charles Bulfinch’s First Harrison Gray Otis House (because it housed SPNEA), which Cummings called “the two most important local monuments,” but the destruction was nonetheless too indiscriminate from Cummings’ perspective. Cummings observed:

Some of the buildings swept away [in the historic West End] were obviously beyond reclamation, but the ancient street pattern, the eighteenth-century street names, and many pleasant small brick town houses [sic] of the period between 1800 and 1850 had survived in only partially run-down condition. Though not necessarily historic landmarks these houses were nevertheless distinguished by their good lines, many original features, and a patina which only time and associations can create.

Cummings lamented that the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) did not pursue “spot clearance,” or demolishing only those buildings which were absolutely beyond repair while maintaining the integrity of the neighborhood. This had been impossible because spot clearance was not funded under the Housing Act of 1949 (which established urban renewal). While it had been incorporated into urban renewal policies by 1954, full clearance had been the only policy option for the West End Project when it was proposed in 1953.

Cummings also argued that one of the greatest harms of urban renewal in the West End would be the negative effect upon tourism, as many people visit Boston to experience the historical legacy that lives on in its old buildings. He continued:

Instead just that much more has been lost of Boston’s individual character and quality which have so long attracted tourists from all over the country. For these many Americans Boston represents a tangible link with the past…Will they not think it something of a paradox in a nation whose architects from coast to coast design countless imitations of New England’s Colonial- and Federal-style houses that here in her most historic city we busily stave down the genuine article-whole streets at a time? Later generations who examine our twentieth-century protestations of interest in an American heritage will find such raids on cultural capital totally incomprehensible.

Most of the essay focused on the West End’s early architectural history rather than the present day. Although critical of indiscriminate neighborhood clearance, Cummings acknowledged that the destruction and replacement of notable buildings had routinely occurred in early Boston. After an extensive discussion of Charles Bulfinch’s property holdings in the West End, before and after losing his fortune in the Tontine Crescent development, Cummings concluded with a personal observation Bulfinch wrote on June 12, 1843, a year before the first American-born architect’s passing. Bulfinch saw the house he designed for Joseph Coolidge, Jr. (built in 1795) being demolished: “I have this morning viewed those [alterations] going on in Bowdoin street. Mr. Coolidge’s noble mansion, trees and all, are swept away, and 5 new brick houses are now building on the spot.” Cummings imagines what Bulfinch must have been thinking as he witnessed the disappearance of one of his creations, a house which once reflected the “new and brilliant architectural style that made Boston in the nineteenth century one of the most attractive cities on the eastern coast.”

Cummings did not merely lament the destruction of historic architecture in the West End; he took action. Cummings recalled in an interview in 2007 that “On one occasion I actually locked horns with Ed Logue, the head of urban renewal in Boston. I don’t like doing this, but I found myself actually engaged in a shouting match.” He described urban renewal in the West End as “one of the greatest black marks against Boston in all its long history.” When urban renewal was inexorable, Cummings aided SPNEA in preserving what they could for future historians and architects. The Bulfinch House on 8 Bulfinch Place (later occupied by the Hotel Waterston in the early twentieth century) was slated for demolition on September 4, 1961. Months before, in May, Cummings and John Obed Curtis measured all remaining elements of the original facade of the Bulfinch House, interviewed the Waterston family for their memories of the old Bulfinch House, and kept some of the bricks for the Society’s archive.

Abbott Lowell Cummings had a long teaching career at Boston University, the University of Masssachusetts Amherst, and Yale University before passing away in 2007.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: Abbott Lowell Cummings, “Charles Bulfinch and Boston’s Vanishing West End” (1961); Jessica Neuwirth et al. “Abbott Lowell Cummings and the Preservation of New England” (2007); WEM – Old West Church; Richard Candee, “Abbott Lowell Cummings, 1923-2017” (2018); James Q. Wilson, “Urban Renewal; the record and the controversy” (1966); Nancy Voye, “Ascher Benjamin’s West Church: A Model for Change”