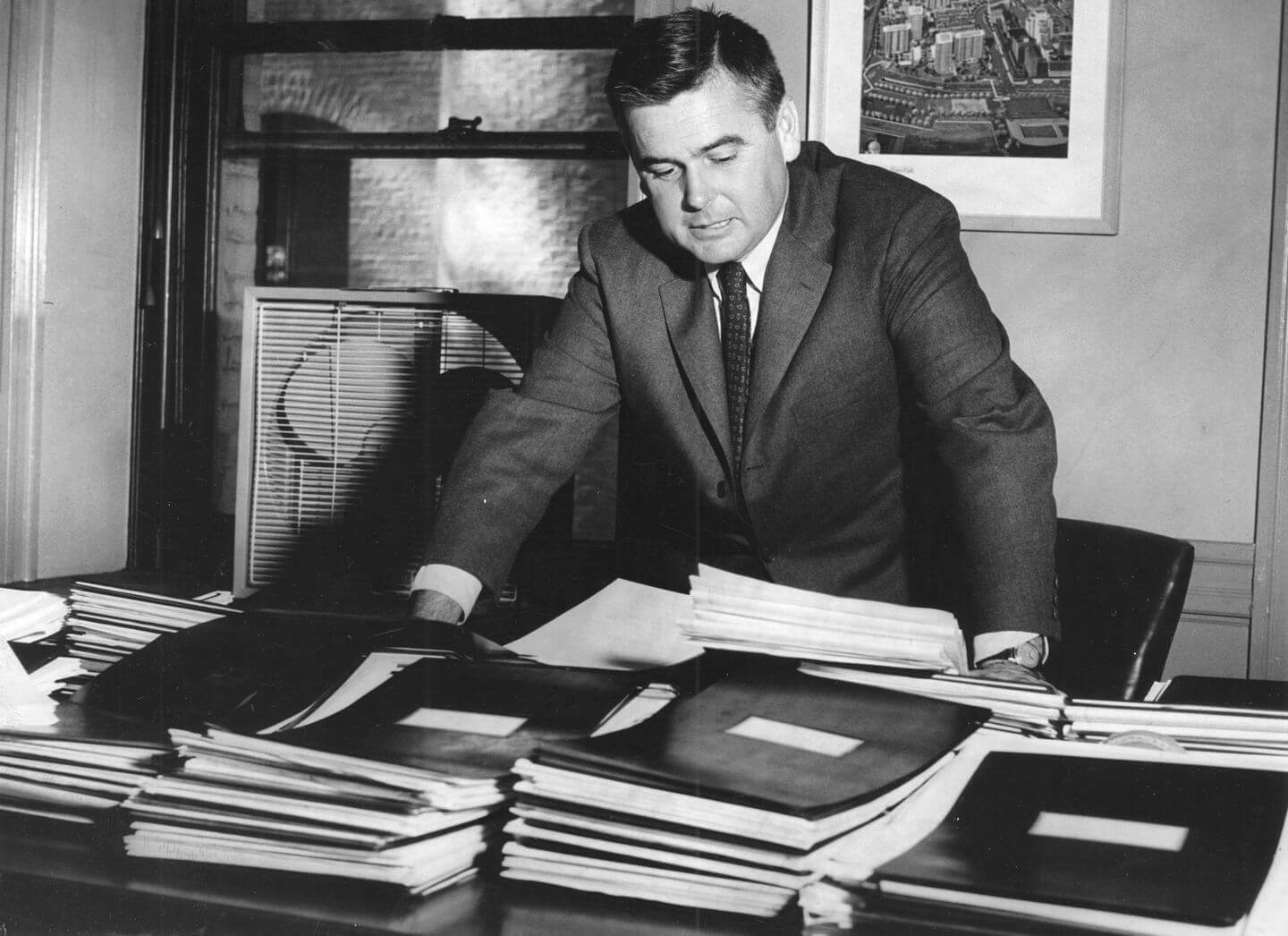

Ed Logue

As director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority in the 1960s, Ed Logue was the highly visible face of urban renewal in the period following the destructive and controversial redevelopment of the West End.

Edward J. Logue was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on February 7, 1921 to Edward J. Logue Sr., a real estate assessor for Philadelphia, and Resina Fay. The oldest of four brothers, he received his undergraduate degree at Yale University in 1942, and all three of his brothers later did the same. While at Yale, Logue was general organizer for the Yale Employees Union. After graduating, Logue enlisted with the Air Force and flew missions in Europe during World War Two; returning from the war, he graduated with a Yale law degree and married Margaret DeVane in 1947. As a lawyer, Logue quickly developed political connections, particularly as a staffer for Connecticut Governor Chester Bowles, a Democrat; although Bowles lost re-election in 1950, he became Ambassador to India and brought Logue along. Logue worked in India under Bowles for two years before he and his wife returned to Connecticut, helping Richard Lee win the mayoral race in New Haven. Logue became Lee’s development administrator, and held the position from 1955-1961; this was Logue’s first position as an urban planner with lots of centralized authority.

Under Logue, New Haven received the most federal urban renewal money per capita of any city in the U.S., and he became a visible public advocate locally and nationally for the projects he directed. In the November 9, 1958 edition of The New York Times Magazine, Logue wrote in “Urban Ruin–Or Urban Renewal?” that previous projects that simply demolished blighted areas were too limited to be successful. He argued that urban renewal had to be comprehensive: in addition to slum clearance and rebuilding there must be “humane relocation of displaced families and businesses–the families preferably being integrated into existing neighborhoods rather than dumped into the enormous projects of the past.” Rhetoric of this sort became even more prominent among urban planners after the demolition of the old West End of Boston in 1958 and 1959, as the mass displacement and psychological harm of old residents made demolition-centered urban renewal less popular. In New Haven, one of Logue’s more controversial projects involved razing historic Victorian-style buildings and replacing them with a downtown shopping center that might attract visitors from the suburbs. According to historian Lizabeth Cohen, because there were not yet tax incentives for preserving historic buildings, Logue and Mayor Lee made a strictly economistic decision: New Haven needed more retail, so the old, in their eyes, had to make way for the new.

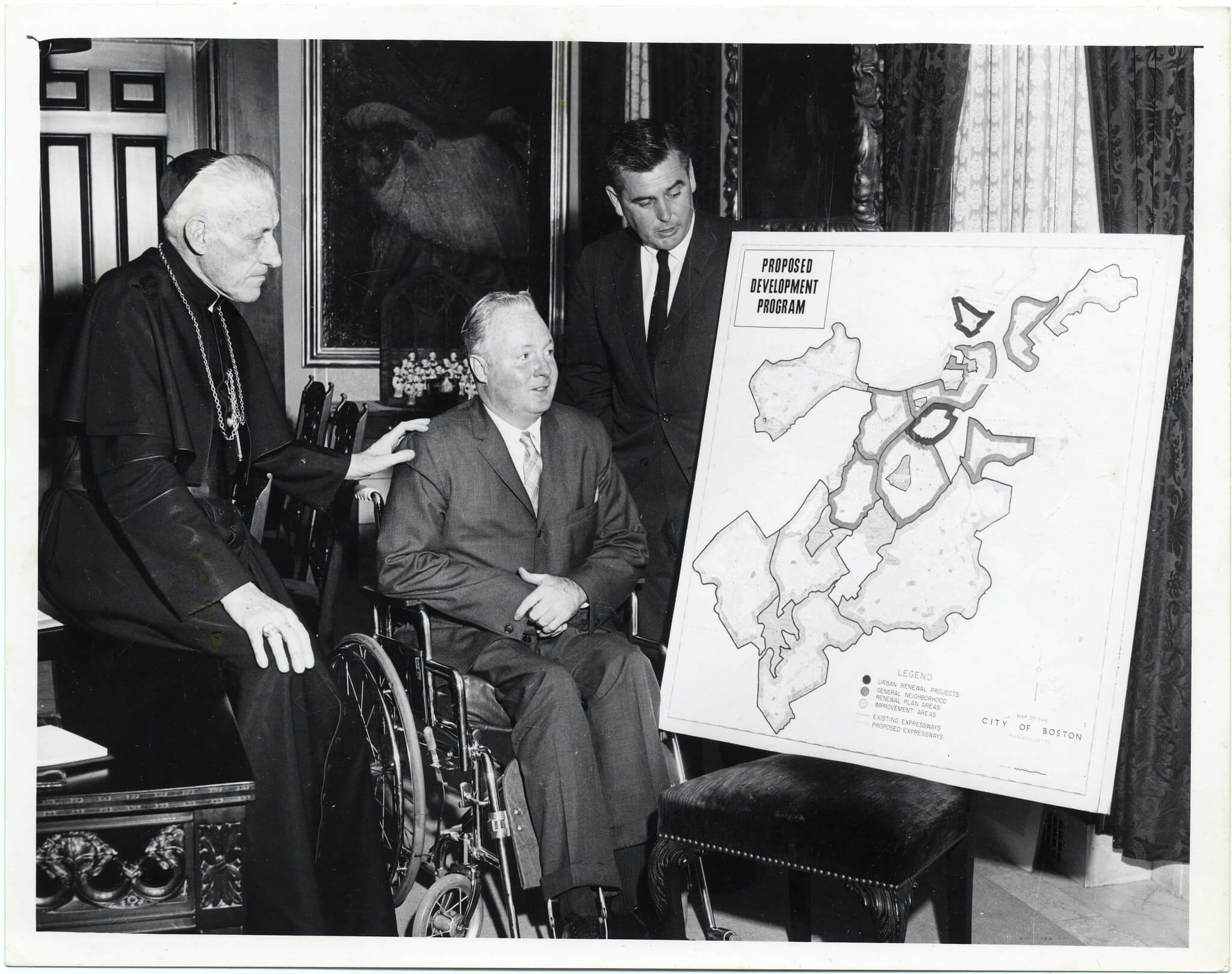

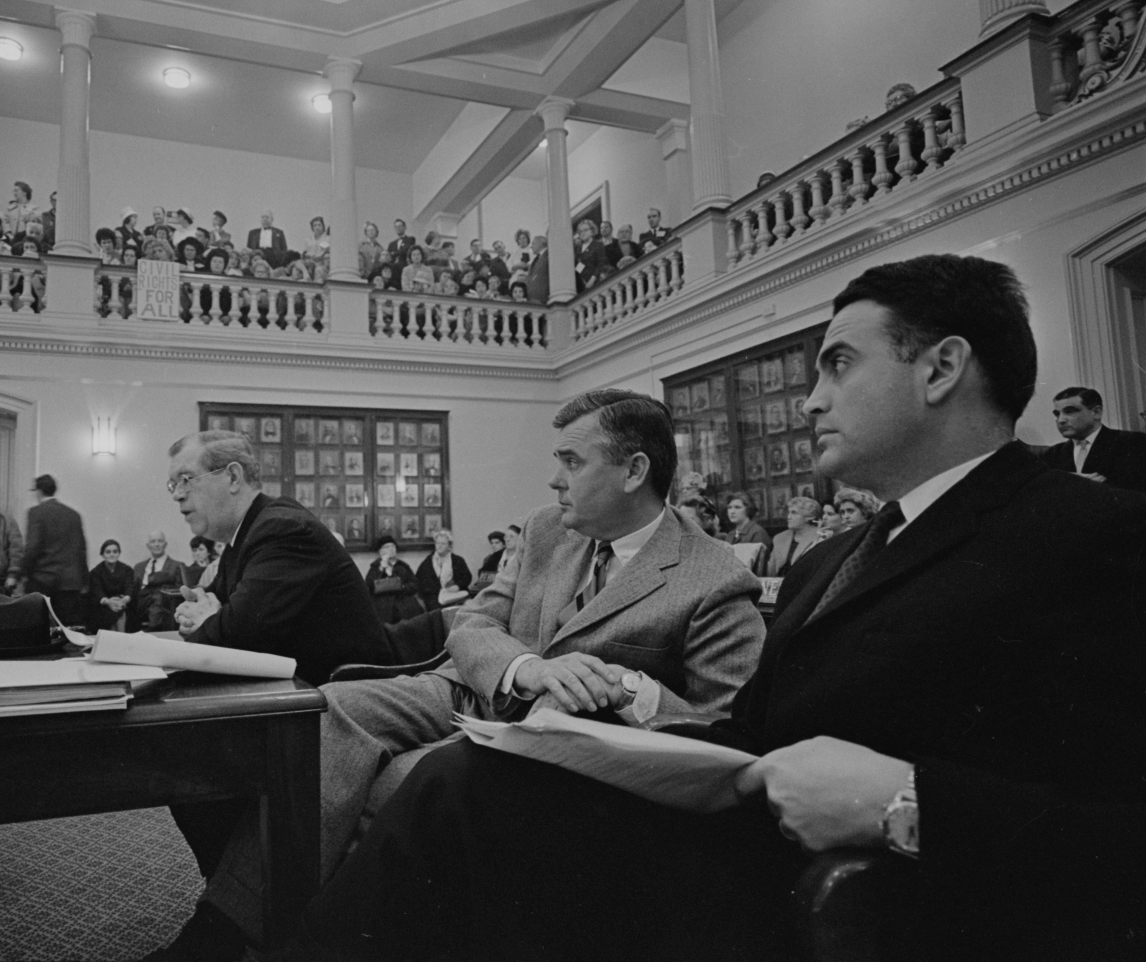

In 1960, Boston Mayor John Collins lured Ed Logue away from his position in New Haven to direct urban renewal in Boston. Logue agreed to the development administrator position at an unprecedented salary of $30,000/year, and stayed in that role until 1967 when he tried unsuccessfully to run for mayor of Boston himself. The Boston Redevelopment Authority approved Logue as executive director in a contentious 3-2 vote on January 25, 1961. Logue was controversial for his attempts to consolidate redevelopment authority in his hands the way he had power in New Haven, and he earlier succeeded in convincing the State House to revise laws to enable a development administrator to lead on planning and redevelopment together. One of the “no” votes was Kane Simonian, whose lawsuit charging that he was illegally demoted despite retaining the “executive director” title was thrown out of court. By May 1961, Simonian was able to lead the BRA’s operations division while Logue was officially development administrator, and the two managed separate projects.

Louge put Simonian in charge of finishing the West End redevelopment project, which Logue — who saw the project as a political and public relations disaster — routinely insisted he had nothing to do with. The BRA demolished the old West End before Logue was brought to Boston, and even then officials were eager to deflect responsibility: Mayor John Hynes put Jerome Rappaport of the New Boston Committee in charge of the project. Rappaport notably reneged on his promise to West End residents that low and middle-income housing would be built for them to move into the redeveloped neighborhood; instead luxury apartments were built to replace the tenements of old. But for people who remember Logue as the public face of Boston’s urban renewal, an image which he intentionally constructed as someone invested with dual authority in planning and development, Logue became a symbol for destructive projects such as what took place in the West End.

Logue’s most famous project was Government Center and City Hall Plaza, designed in 1962 and completed in 1968. His original plan would have destroyed two nineteenth-century buildings in the process, but protests successfully pressured Logue to revise the plans and avoid their demolition. Government Center, which replaced Scollay Square, had become another symbol for critics of urban renewal: according to a New York Times report on Logue’s activities in New York as president of the Urban Development Corporation, ““The most clearly visible sign of Logue’s Boston years” is the downtown Government Center…No one disputes that the area has been urban-renewed, the fight is about the people who have been urban renewed out.” Sociologist Herbert Gans, author of The Urban Villagers, was critical of Logue in 1970 for his commitment to the federal framework for urban renewal that pushes out poor people from residences instead of trying to alleviate poverty. Activist Jane Jacobs held a public debate with Ed Logue at the Museum of Modern Art in 1962 after publishing The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Where Jacobs criticized Logue’s commitment to demolishing old buildings, Logue argued that Jacobs’s position was suited for “comfortable suburbanites who like to be told that neither their tax dollars nor their own time need to be spent on the cities they leave behind them at the close of every workday.” Logue had also clashed with famed urban planner Robert Moses in the middle of the 1970s, when Logue unsuccessfully fought to have low-income housing built in the wealthy Westchester suburbs, and Moses allied with local opponents to block the project.

Ed Logue continued to be a noted expert voice on urban planning until he died on January 27, 2000. Logue’s legacy matters to histories of demolition and urban renewal in the West End not because he was its architect, but rather because his decisions after the event were influenced by an awareness of destruction gone too far. Historian Lizabeth Cohen argues that “In Boston, [Logue] had carefully distanced himself from the old-style leveling of the West End and sought greater balance, coming to value the preservation of historic buildings downtown as well as in neighborhoods like Charlestown and the South End.” Herbert Gans, in a 2006 retrospective on Jane Jacobs, has a different memory, commending he and Jacobs’ “action to keep Edward Logue out of New York City when he was still “clearing” “slums.”” [quotes are from Gans]. Ed Logue’s historical legacy is complicated by upon the places where he led redevelopment – New Haven, Boston, or New York – but his centrality to major political and social conflicts over urban renewal is undeniable.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: The Harvard Gazette; Friends of Edward J. Logue; Introduction to Edward Joseph Logue papers; “Urban Ruin–Or Urban Renewal?” by Edward J. Logue (New York Times, November 9, 1958); Herbert Gans, “Jane Jacobs”; Richard Schickel, “New York’s Mr. Urban Renewal” (New York Times, March 1, 1970, TimesMachine); The New Yorker; Architect (The Journal of the American Institute of Architects); New Haven Register; Saving America’s Cities: Ed Louge and the struggle to renew urban America in the suburban age by Lizabeth Cohen (2019)

1 Comment