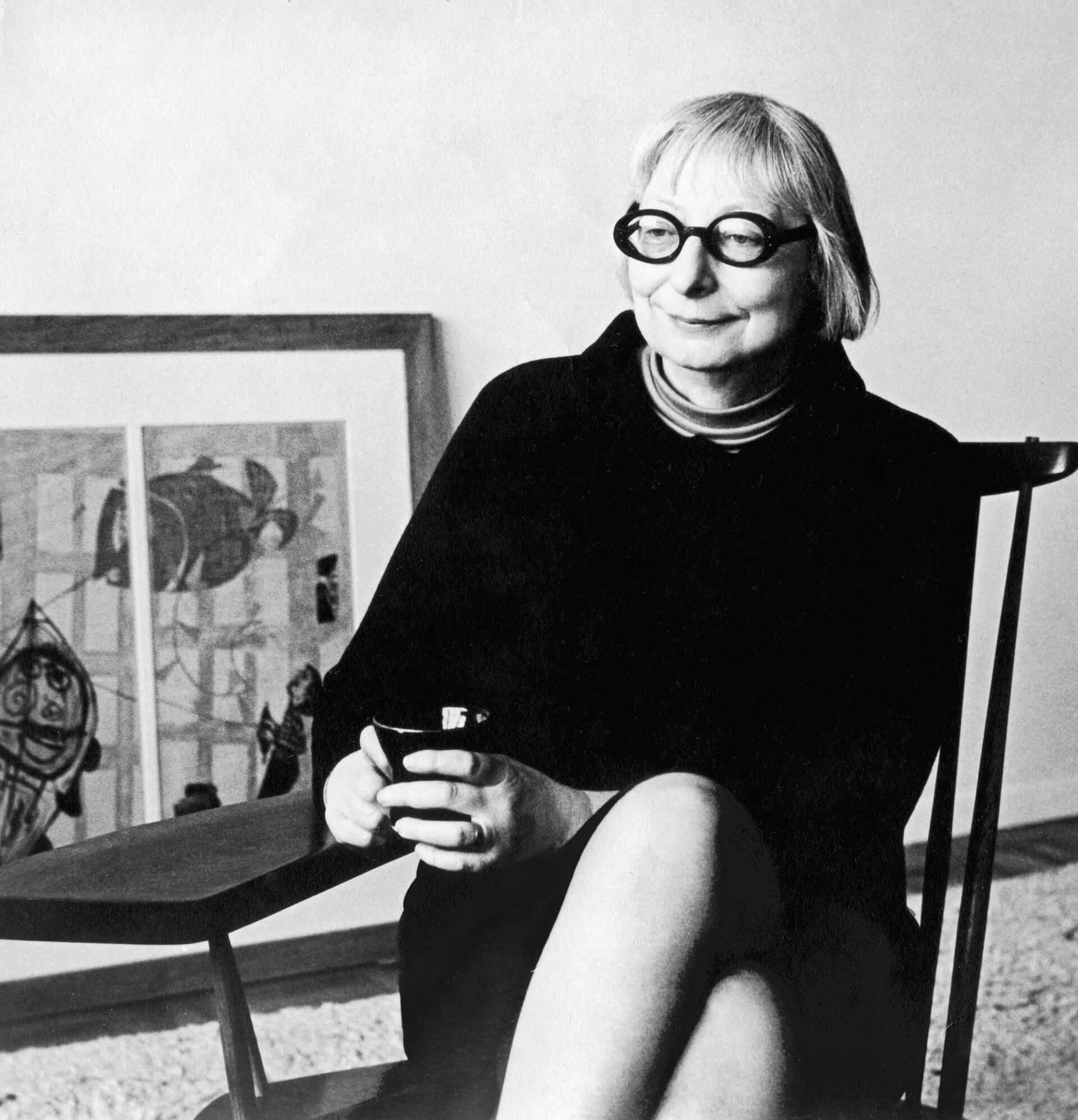

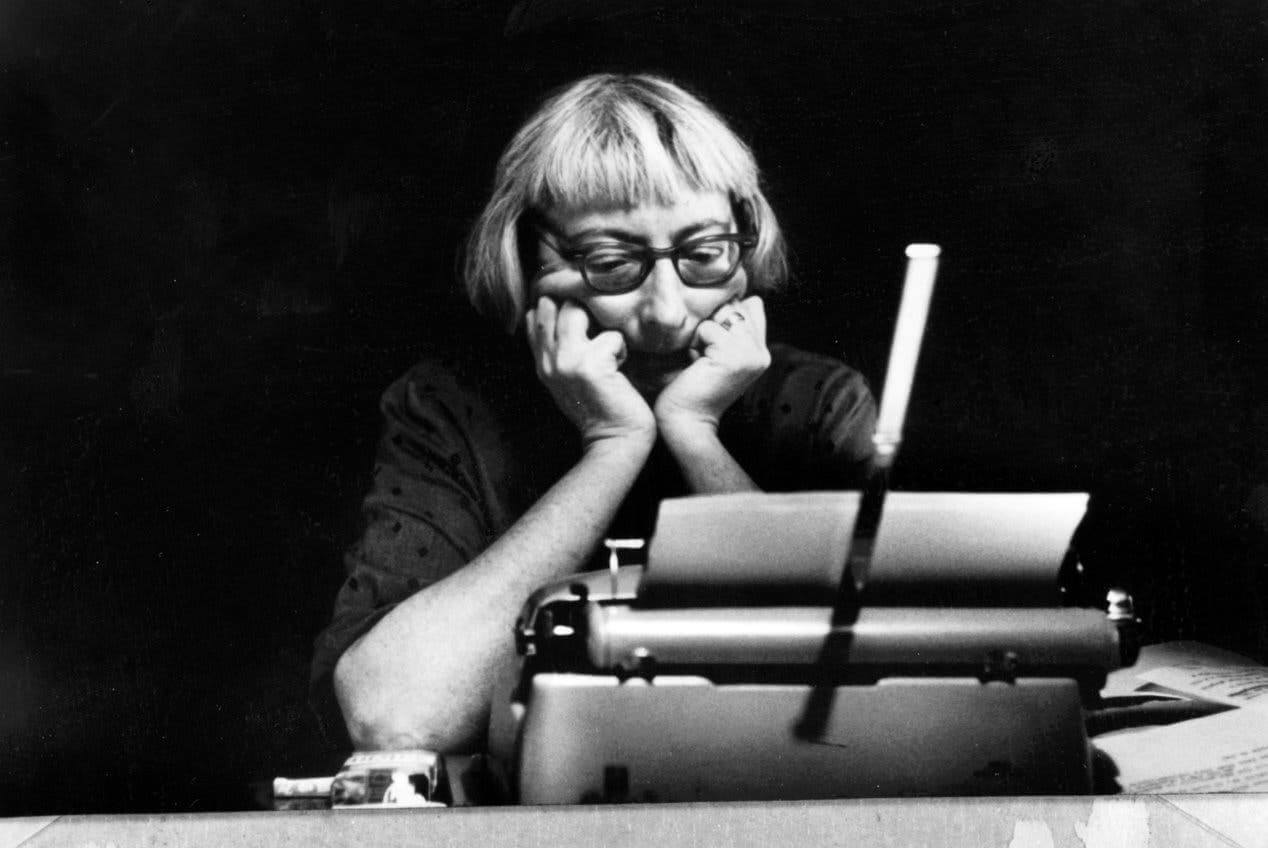

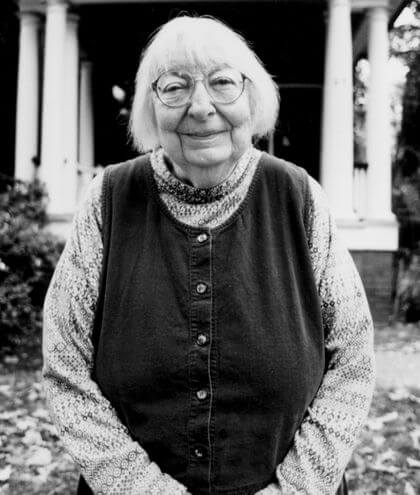

Jane Jacobs

Jane Jacobs was a journalist, author, and activist who argued for the prioritization of people in urban planning projects.

Jane Jacobs was born in 1916 in Scranton, Pennsylvania to the Butzner family; her father was a family doctor, and her mother was a former nurse and teacher. Biographies of Jacobs frequently begin with her graduation from high school, for soon after she became an unpaid intern in the newspaper business, an assistant to the Scranton Tribune’s editor for the women’s page. In 1934, Jacobs moved to New York City during the height of the Great Depression. Although work was scarce, Jacobs was hired by magazines and newspapers as a freelance writer. She regularly covered stories from working-class locales, owing to her keen interest in the socioeconomic and cultural conditions of work and city life. Jacobs has recalled her long walks in the city as being crucial to her growing familiarity with New York’s working-class districts.

At the advent of America’s entry into World War Two, Jacobs worked for the Office of War Information, having past experience as a stenographer (one of the jobs she held in New York prior to freelance writing). She met her future husband, Robert Hyde Jacobs, an architect, from the Office of War Information, and they married in 1944. Because Robert was an architect, Jane developed an interest in city planning and urban design. In 1952, Jane became an associate editor for Architectural Forum magazine, working in that position for a decade.

While editing Architectural Forum, Jacobs honed her critique of urban renewal. In 1956, she gave a speech at Harvard University on her position that urban renewal projects implemented then were antithetical to vibrant, safe, liveable cities. Jacobs also gave a lecture in the same decade at Boston College after the old West End’s demolition by urban renewal, and similarly criticized that project as a top-down imposition that undermined a tight-knit, working-class community. Jacobs wrote “Downtown is for People” for Fortune magazine in 1958, and argued that urban planners with a ten-thousand-foot view were too invested in buildings over people, and that a top-down model for planning is unhelpful, compared to what one learns when they “get out and walk” – appropriately connected to her early experience. Jacobs resisted the grand designs of planners like Robert Moses, one of New York’s most influential twentieth-century architects, because his vision for slum clearance, expressways slicing through established neighborhoods, and high-rises, threatened the vibrancy of old areas. As Jacobs’ argued in the Fortune article: “Think of any city street that people enjoy and you will see that characteristically it has old buildings mixed with the new. This mixture is one of downtown’s greatest advantages, for downtown streets need high-yield, middling-yield, low-yield, and no-yield enterprises.” Jacobs defended this perspective further in the seminal 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and The Economy of Cities in 1969. Jacobs not only argued for “mixed-use” development and community input in planning as essential to vibrant cities, she also disagreed with conventional wisdom about high urban density. Jacobs believed that “The presences of great numbers of people gathered together in cities should not only be frankly accepted as a physical fact – they should also be enjoyed as an asset and their presence celebrated.” The old West End was concerning to Boston’s urban planners because of its high density, among other purported issues, yet Jacobs would have seen the old West End as more alive for that reason.

Jacobs’ ideas were not uncritically accepted, even by critics of urban renewal such as Herbert Gans, author of The Urban Villagers, his ethnographic study of the Italian-American community in the old West End. Gans acknowledged that “the widespread popularity of Jacobs’s book [in 1961]…helped to turn the tide against the bulldozer, at least in large American cities,” although he emphasized that grassroots protests against urban renewal were most effective at forestalling some undesirable projects. However, Gans argued that Jacobs’s perspective was limited by “the fallacy of physical determinism,” meaning that she made too many assumptions about the social life of a city from its physical and spatial appearance; she had also, in Gans’ estimation, overlooked the status-seeking of the middle class – attached to houses and cars – as a crucial motivation for their leaving cities.

Jane Jacobs died on April 25, 2006, but her legacy lived on a year later when friends founded Jane’s Walk, a worldwide event centered around free walking tours that explore Jane Jacobs’ ideas about city life and urban planning. In 2015 and 2019, the West End Museum hosted Jane’s Walk in Boston, and connected Jacobs’ ideas about urban planning to the exhibits of the Museum, such as “The Last Tenement.”

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Project for Public Spaces; “Jane Jacobs: her life and work” by Gert-Jan Hospers (European Planning Studies, 2006); Britannica; “Downtown Is For People” by Jane Jacobs; The West End Museum; Beacon Hill Times; Summary of “The Fallacy of Physical Determinism” by Herbert J. Gans