Marc Fried and the Human Cost of Urban Renewal

Soon after the bulldozers of urban renewal began clearing land, experts in various fields focused on the effects of development projects and the human cost paid by affected communities, such as Boston’s West End. Marc Fried, a Harvard educated psychologist, interviewed hundreds of displaced West End residents in the late 1950’s to assess the emotional effects of relocation. The results of his work, and that of other dedicated researchers, helped turn public opinion against top-down urban renewal and inspired community activism throughout the United States.

Marc Fried, named Abraham at birth, was born on May 29, 1922 in Newport, Rhode Island. His family moved to the South Bronx in New York City when he was a child. In 1940 he graduated from Stuyvesant High School and served in Europe as a medic in the U.S. Army during World War II. After the war, he graduated from City College of New York and went on to receive a doctorate of psychology at Harvard University. He married Joan Zilbach in 1952 and they had four children. A pianist since childhood, he was also a composer, sculptor, and painter. He worked as a psychologist for the Massachusetts Mental Health Center and from 1957 to 1966 and served as the research director at the Center for Community Studies.

In 1957, Fried became director of the Center for Community Studies with the immediate task of researching the psychological effects of forced relocation in Boston’s West End neighborhood. Erich Lindemann, Chief of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor at Harvard University, founded the Center with the goal of expanding the field of community and social psychiatry. Renowned for his study of acute grief in the wake of the deadly 1942 fire at Boston’s Cocoanut Grove nightclub, Lindemann was concerned about the human implications of the upcoming West End urban renewal project which would bring about the destruction of 48 acres of the neighborhood and the displacement of 2,700 families. He tasked Fried to uncover “what kind of families, from what kind of origin, will be damaged most by this process?”

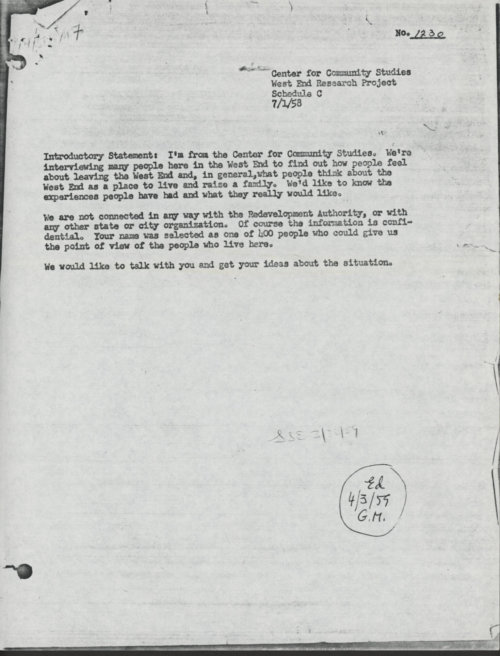

In the West End, Fried led a team which gathered qualitative data from residents by embedding themselves in the neighborhood culture and performing hundreds of interviews. The team sought to document the pre-relocation and post-relocation consequences of forced removal. They asked displaced residents:

Did you feel sad or depressed when you moved?

Describe how you felt.

How long did these feelings last?

How did you feel when the buildings were torn down?

This simple methodology effectively measured levels of high psychological distress resulting from relocation; a distress caused not only from the loss of their physical homes, but also of social systems, familiar ties, and, in many ways, their identities. Fried associated the sense of loss caused by this disruption of community with a form of bereavement — “intense, deeply felt and at times overwhelming”. In 1963 he published his landmark study “Grieving for a Lost Home: Psychological Costs of Relocation.”

Before Lindemann’s study of the Cocoanut Grove Fire, the medical establishment did not consider grief a psychiatric issue. Less than 20 years later, Fried concluded that cohesive neighborhoods provided residents with a feeling of “rootedness” that is essential in maintaining a sense of identity. Urban renewal projects and the devastation they caused by clearing neighborhoods and relocating residents brought on “root shock”, resulting in a complex traumatic stress. One of Fried’s respondents, a Mrs. Borowski, on seeing her former residence torn down, lamented that “it’s just like a plant . . . when you tear up its roots, it dies…” The qualitative data provided by Fried’s study demonstrated that individuals can truly grieve the loss of a place and a way of life, and inspired the alteration of approaches to community mental health care and, some experts say, the trajectory of urban renewal projects in the United States.

Fried’s study of the West End was highlighted in Urban Renewal: The Record and the Controversy, a collection of studies produced by members of the Joint Center for Urban Studies, a collaboration between Harvard University and M.I.T. Besides Fried’s chapter on the emotional effects of relocation on a community, the book included works by other influential voices in the urban renewal discussion, such as Herbert Gans (Urban Villagers), Martin Anderson (The Federal Bulldozer), and activist Chester Hartmann. In 1973, Dr. Fried published what would become a classic in sociological studies, The World of the Urban Working Class, which used the years of data he collected in the West End to describe the everyday socioeconomic life in the neighborhood.

Later, Fried went on to found the Institute for Psycho-Social Studies at Boston College, where he served as a professor and researcher for 35 years. After retiring, he studied music and art, and in 2001 he received his license to practice clinical psychology from the Massachusetts Institute of Psychology. Marc Fried died surrounded by family in 2008 in Lewiston, Maine at the age of 85. He is remembered as a champion for the West End, for his impact on the fields of community and environmental psychology, and his commitment to social justice.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Boston Globe, May 18,2008, p.25.; Duhl, Leonard J., and John. Powell. The Urban Condition; People and Policy in the Metropolis, Edited by Leonard J. Duhl with the Assistance of John Powell. Basic Books, 1963.; Fried, Marc. “Grieving for a lost home”, in Urban Condition: People and Policy in the Metropolis. 1963.Ed. L J Duhl (Basic Books, New York) p. 151-171.; Fried, Marc. The World of the Urban Working Class. Harvard University Press, 1973.; Ramsden, Edmund, and Matthew Smith., “Remembering the West End: Social Science, Mental Health and the American Urban Environment, 1939–1968.” Urban History, vol. 45, no. 1, 2018, pp. 128–149; Wilson, James Q., editor. Urban Renewal; the Record and the Controversy. M.I.T. Press, 1966.