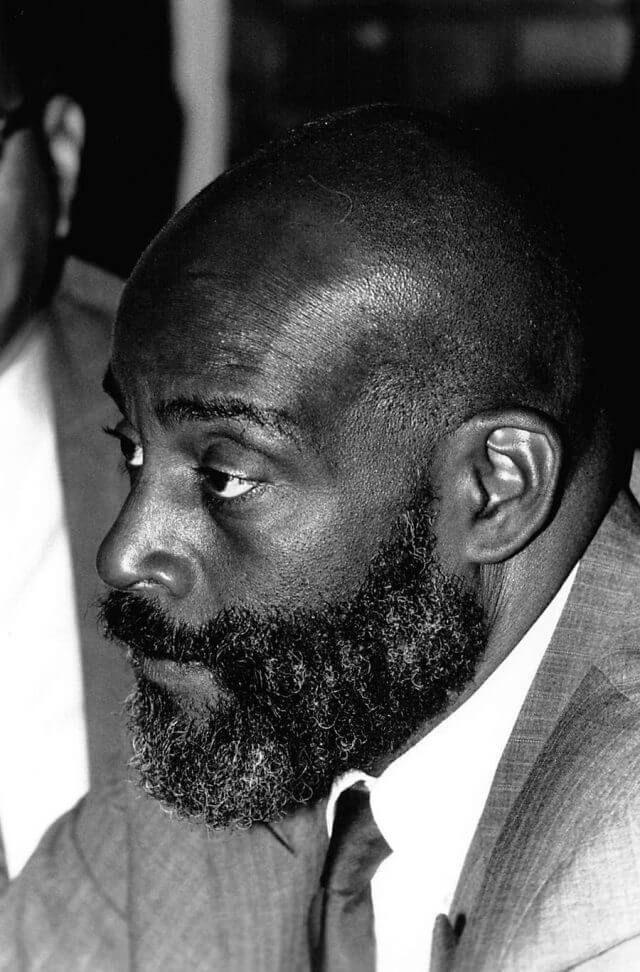

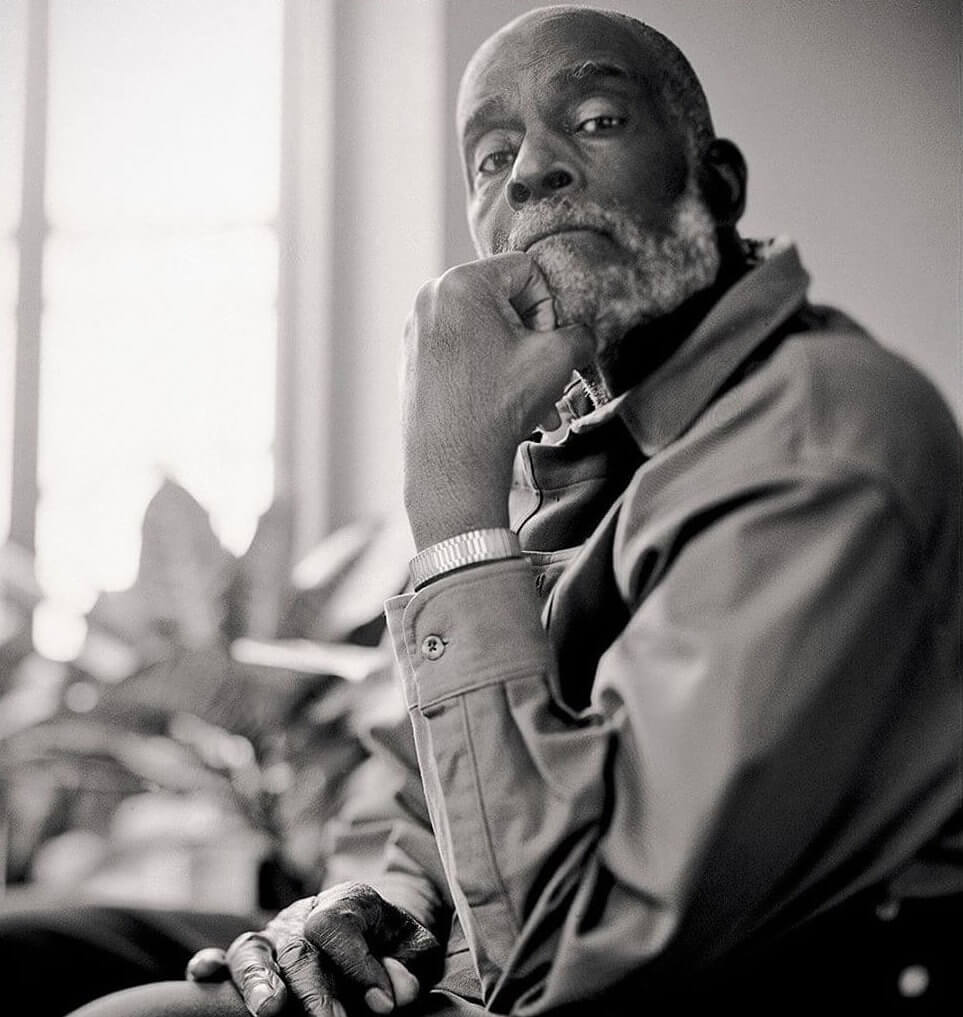

Remembering Mel King

Mel King was one of Boston’s most influential Black political figures, who stood against destructive urban renewal in his native South End. King made a difference as a community organizer and State Representative, and he was the first Black person to reach the general election for Mayor of Boston in 1983. King passed away on March 28, 2023 at the age of 94.

Melvin “Mel” H. King was born to Ursula and Watts King on October 20, 1928, in Boston’s South End. Mel’s mother was from Guyana and his father from Barbados; they met in Nova Scotia before immigrating to the South End. King had seven siblings, all born between 1918 and 1938. The King family resided in the New York Streets neighborhood, the twenty-four acres of the South End where the streets were named for cities along the Erie Canal, in honor of the railroad connecting Boston to Albany in 1842. The New York Streets were a diverse section of the South End, representing the Black, Jewish, Armenian, Chinese, and Italian communities. After graduating from Boston Technical High School, King attended Claflin University, the oldest historically black university in South Carolina, where he earned a bachelors degree in mathematics in 1950. In 1951, King earned a master’s degree in education from the Teacher’s College of the City of Boston, and taught math for two years.

While King was in South Carolina, his mother Ursula sent him newspaper clippings from the Boston Herald-Traveler, which referred to the New York Streets as “Skid Row” as the city prepared to raze the neighborhood. In 1952, the King family and hundreds of others were evicted as the City of Boston demolished the New York Streets area to clear ground for light industry and the new Herald-Traveler headquarters. King, in his 1981 book Chain of Change, remarked that “labeling those streets as slums depersonalized the issue, and blocked out any understanding of the impact urban renewal would have on the lives of the people, like my family and friends, living there, and provided a rationale for replacing ‘undesirable’ elements of Boston with less troublesome ‘light industry.’” By 1957, the city demolished 321 buildings in the New York Streets neighborhood and displaced more than 1,000 residents. For King, the Herald-Traveler articles and the disparaging words of Mayor Hynes did much to dehumanize the neighborhood: “They called it Skid Row…If they can name you, they can claim you.”

In 1953, King directed youth and gang intervention programs at the Lincoln House (a South End settlement house) and the United South End Settlements (USES). The South End was targeted for urban renewal by Boston Mayor John Hynes, whose “New Boston” platform promised to use federal funding, guaranteed by the Housing Act of 1949, for “slum clearance.” USES attempted to act as a bridge between government and community members in the urban renewal process. This put the organization at odds with Mel King, who advocated for greater neighborhood control in urban planning instead of from activists’ perspectives, the USES’s paternalism, and collaboration with the destruction of neighborhoods. King was briefly fired from USES, until protests from the community led to his being re-hired as a community organizer. King subsequently founded the Community Assembly for a United South End (CAUSE) to organize South Enders to make their voices heard in urban planning.

During the 1960s, King ran for the Boston School Committee three times, and became director of the Urban League of Greater Boston in 1967. In 1968, King again protested urban renewal when the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) planned to demolish South End homes at the corner of Dartmouth Street and Columbus Avenue to build a parking lot. King led an occupation of the site slated for demolition by creating a “Tent City,” with up to 400 South Enders demonstrating against urban renewal from a community of makeshift tents. Bill Russell, star of the Boston Celtics, provided food to the demonstrators from his South End barbeque restaurant, Slade’s. Twenty years later, in 1988, the mixed-income housing built on that very lot was named Tent City, in honor of the grassroots action led by King.

In 1973, Mel King became a State Representative in the Massachusetts legislature, representing the 9th Suffolk District. As a state representative, King was responsible for successful legislation on issues such as healthy food and preserving community television. He also advocated for desegregation of Boston’s schools, and worked with Senator Joseph Timilty (D-Mattapan) to record public statements asking for peace and civility during the implementation of court-ordered busing. Busing in Boston generated racist backlash from some white South Boston residents, who resorted to throwing rocks at school buses and other acts of violence. In 1983, Mel King ran for Mayor of Boston against Ray Flynn, the Boston city councilor who represented South Boston. King became the first Black person ever to be on the general election ballot for Boston mayor. Both King and Flynn were advocates for working-class residents of Boston, but Flynn was opposed to busing and abortion rights. Mel King’s “rainbow coalition,” inspired by Rev. Jesse Jackson’s movement of that name, united Boston’s grassroots movements in an anti-racist and feminist coalition. On November 15, 1983, Flynn won the mayoral race with 65.6% of the vote, to King’s 34.4%. Mel King, in his concession speech, congratulated Flynn for a campaign which “does honor to Boston neighborhoods and to the people who have far too long been ignored or oppressed.” Yet he hoped that Flynn would help “foster an identity in Boston which will eradicate the pervasive and destructive aspects of racism.” King and Flynn maintained a long friendship, going back to their days playing basketball together in their youth, and continuing up to recent years, when they co-taught lessons on civic engagement for Boston school children in 2016. King was also a longtime adjunct professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he taught in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning from 1970 to 1996 and directed the department’s Community Fellows Program.

Mel King passed away at the age of 94 on March 28, 2023. King is remembered as one of Boston’s greatest champions of social justice, particularly the empowerment of all Boston residents in the development of their neighborhoods.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: AP; The West End Museum; ProQuest/Boston Globe (“Flynn wins in a big way, 66%-34%,” November 16, 1983; “Neighborhood Associations Demanding Say in Planning,” June 5, 1962; “King, Timilty to make TV appeal for safety in schools,” September 1, 1974); SNAC; City of Boston; The History Makers; WBUR; The Harvard Crimson; LinkedIn; Dirty Old Boston; Bay State Banner; Rubin, “Insuring the City”.