The Committee to Save the West End

In the late 1950s, the Committee to Save the West End brought residents and political leaders together to vigorously oppose the Boston Redevelopment Authority’s plan to raze 50 acres of the neighborhood.

The Committee to Save the West End was founded in the late 1950s by longtime resident Joseph Caruso and five other West Enders to resist the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA)’s plan to raze 50 acres of the neighborhood for urban renewal. Caruso’s family immigrated to the West End from Italy in 1931 and resided on Green Street, above a fish market. He joined other West Enders, including the Polish-American community leader Wanda Zachewicz, to establish the Committee to Save the West End by renting a storefront for the organization on Staniford Street. The storefront’s windows declared the presence of the “West End Minutemen,” a callback to Revolutionary War-era Boston, and featured the iconography of the Gadsden flag: a rattlesnake with the motto “Don’t Tread On Me.” Another member of the Committee to Save the West End, who often served as the face of the group during public hearings, was Joseph Lee, Jr., the philanthropist and public recreation advocate then serving as Chair of the Boston School Committee. Lee helped create the Committee to Save the West End after a young West End resident, Frank Lavine, ran to Lee’s home on South Russell Street to hand him a pamphlet describing Mayor John Hynes’ urban renewal plan for the West End. Historian Jim Vrabel, in A People’s History of the New Boston, documented Lavine’s recounting of his conversation with Lee: “‘When I got to his house,” Lavine recalled, “I said, ‘Joe. Joe. We’re all gettin’ kicked out.’ I’ll never forget the look on his face after he read the pamphlet and said to me, ‘They wouldn’t dare!’”

On May 14, 1953, over 500 “irate West End residents” flooded a City Council meeting to protest Hynes’ urban renewal plan for the West End. Since then, the Committee to Save the West End fought tirelessly to preserve the neighborhood and assert their community’s voices. Committee members pursued letters to the editor, which first appeared in 1956. Frank Levine wrote a letter to the Boston Globe printed on August 21, 1956. Listed as “Member, Committee to Save the West End,” Levine argued that developers (whom he called “real estate sharks”) viewed the West End as real estate worth exploiting only because West Enders themselves made so many improvements to their neighborhood. He described these improvements in full:

We West Enders have fought many battles to bring about numerous improvements in this area. Incidentally, the rest of the city, and the Commonwealth, have benefitted. To cite a few of the things which were won for all the citizens by the people of the West End: The improved Esplanade, the M.D.C. swimming pool, wading pool and bathhouse, the playground and ball fields, the two separate sailing programs on the Charles River. In addition to those, the Hatch Memorial Shell and the Science Museum were built by the West End.

Levine had also made a point that resonated with many West Enders at the time, that the city was deliberately “refusing our neighborhood the same sanitation services received by other sections of the city” in order to weaken residents’ willingness to stay and engineer the image of the neighborhood as a “slum.” West Enders were even discouraged by the city from fixing up their residences, once long-term plans to demolish the neighborhood were announced. James Campano, former resident and president of the West End Museum, recalled much later that “Around 1954 they said that if you fix up your apartment buildings, you might not get your money back because they’re going to end up getting taken. So street cleaning stopped, garbage pickup became sparse and they created an image of a slum.”

Wanda Zachewicz made a very similar point about recent improvements by West Enders, for the neighborhood and the city at large, in her letter to the Globe on September 19, 1956. She wrote that “For years our West End leaders have fought to use money left in trust for this purpose: To better the river area.” After vividly describing the joys that Boston residents experience from watching the Boston Symphony Orchestra perform at the Hatch Shell, and sailing on the Charles River or visiting the Science Museum, Zachewicz concluded, “we helped build these recreational advantages, and as Americans, living in a free country, we will fight with everything in our power to keep them for a free West End.”

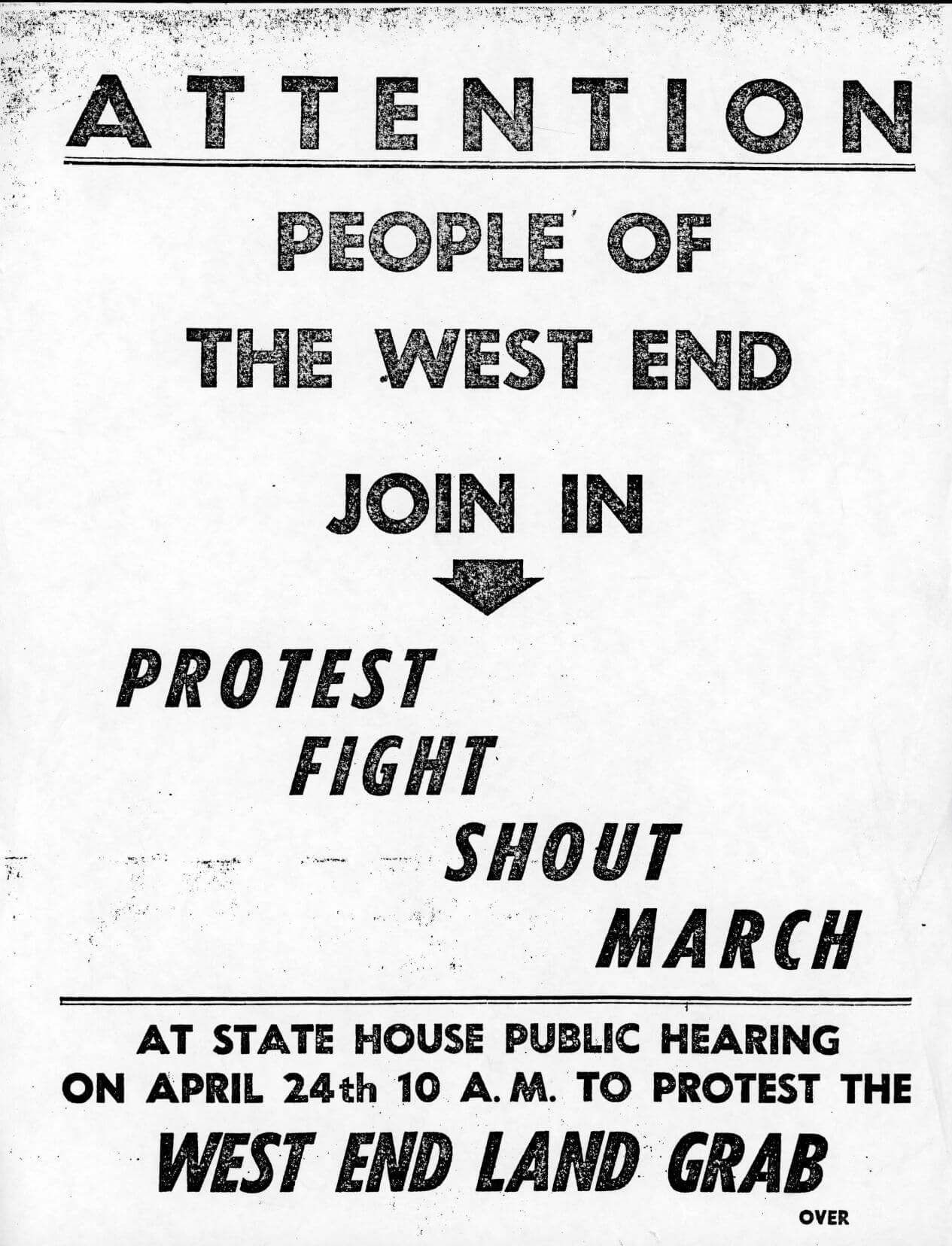

The Committee to Save the West End produced and distributed leaflets against urban renewal in the West End, and made a forceful presence at city council and state housing board hearings. In April of 1957, Joseph Lee declared that he and the Committee to Save the West End would “go straight to the Supreme Court with our fight” if needed. The Globe often called Lee the leader of the Committee (or wrote that it was “his” committee), most likely because of his elevated political role in Boston. But Lee was not the sole driver of the Committee, and neither was he the only politician who supported West Enders’ fight. In June of 1956, Lee joined Senator Mario Umana and Representatives Christopher Iannella and Charles Capraro to produce, with their own money, 4,000 copies of a twelve-page pamphlet denouncing Hynes’ urban renewal plan as a favor to developers. The pamphlet argued that “the city is not seizing our homes because they are ‘decadent, substandard or blighted’” – referring to the language of the Massachusetts General Laws granting urban renewal powers – but rather because “greedy elements have seen a good thing and want to grab it.” Frederick Cronin, chair of the Boston Housing Authority, accused these political figures of “trying to make a play as saviors of the people,” but Lee, who lived a half-block away from the urban renewal project site, replied that Cronin was “certainly making a political play himself when he wants to use the power of the government to drive poor people out of their homes to make room for affluent strangers.” Iannella, who lived on 10 McLean Street in the West End, said that Cronin’s words reflected the “pig-headed attitude of some people in our government.”

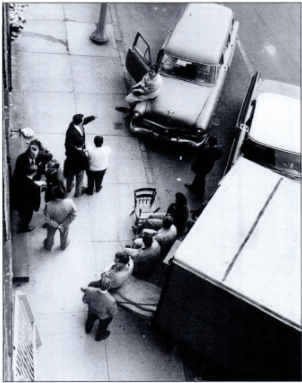

Although the Committee to Save the West End had many supporters behind it, the Boston City Council unanimously approved the $30 million urban renewal project in the West End on July 22, 1957. The Committee took a lawsuit against the project all the way to the Supreme Judicial Court, which ultimately approved its legality. The Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) was created in the fall of 1957 to plan and develop urban renewal efforts in the city. When the BRA held a public hearing at the West End Branch Library, on November 16, 1957, hundreds of West Enders attended the meeting or picketed outside; many were ejected before the meeting began. Some held signs proclaiming, “Don’t Give the West End to Rappaport,” referring to lawyer Jerome Rappaport, who had deep political ties to Mayor Hynes and belonged to the development team that received the contract to tear down the West End and build high-rise, luxury apartments. Although the BRA acknowledged the West Enders’ resistance, where one board member admitted that they were “impressed with the protest,” the BRA quickly approved the urban renewal plan on the premise that “the process had gone too far to be reversed.”

Despite the BRA’s message that the destruction of the West End was inevitable, West Enders continued to fight, to the point where over 500 residents rallied on Staniford Street the night of May 5, 1958. Residents threatened to march on City Hall two weeks from then if Mayor Hynes did not change his mind about the urban renewal plans after negotiations with the Committee. Representative Capraro spoke to the crowd about the stories he heard of BRA representatives telling West Enders who asked about where they would go after the seizure of their homes, “That’s your problem, not ours.” Frederick Langone, another member of the Committee and later elected to the City Council in 1961, told rally goers that federal housing inspectors would be visiting their homes within the week to assess information such as the number of rooms for the purposes of relocation. Unnamed spectators yelled “Don’t let them in!” and “They’ll get in over our dead bodies!”

West Enders’ resistance to urban renewal continued up to 1960, even once the damage was done, when Elizabeth Blood and two of her daughters refused to leave their home on Charles Street and watched the movers cart off their possessions. Although the Committee to Save the West End did not succeed at forestalling the neighborhood’s destruction, their efforts represented a vital movement to empower, not displace, existing residents when making improvements to cities.

Addendum:

Joseph Lee Jr. had a successful public career after the destruction of the West End as a member of the Boston School Committee. Unfortunately, that public career leaves Lee with a tarnished legacy. Despite his advocacy for the rights of West Enders, Lee insisted that decaying public schools in Roxbury and other predominantly Black neighborhoods were of little concern. He became a vocal opponent of desegregating Boston Public Schools, and was one of the most vocally racist members of the School Committee under Louisa Day Hicks. He was ultimately a part of the resistance to integrating Boston’s schools that led to its disastrous experience with bussing in the 1970s.

Joseph Lee Jr. was a key voice in resisting the destruction of the West End, and a vocal advocate for the community before urban renewal. He founded Community Boating, and made the lives of thousands of West End kids better. Lee had the opportunity throughout his career to do the same thing for the children of other neighborhoods – but he failed to do so. He was a respected voice that stood against his peers in defense of the West End. He could have done the same for many other neighborhoods, but when those neighborhoods were Black he refused; choosing to stand with those he’d fought against in an attempt to save the West End.

By Sebastian Belfanti; Source: Kozol, j.; Death at an Early Age (1967)

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Boston Globe (“West Ender Takes Up the Cudgel; District Still Vigorous, Full of Fight” [August 21, 1956, page 16]; “West End Far From Ghost Town” [September 19, 1956, page 20]; “Lee to Press Fight Against West End Plan” [April 2, 1957, page 23]; “City Council OK’s $30 Million Urban West End Project” [July 23, 1957, page 8]; “West Enders in Threat to March on City Hall” [May 6, 1958, page 29]; “Wanda Zachewicz; West End Community Leader” [February 15, 1985, page 63]; “Joseph ‘Bepo’ Caruso, 84, activist in West End” [March 20, 2008]), Huntington News, The West End Museum (“The Last West Enders”), Anthony Sammarco, Boston’s West End (Google Books, 1998), Jim Vrabel, A People’s History of the New Boston (2014, pages 13-15)

1 Comment