The Creation of the US Federal Urban Renewal Program

While the demolition of the West End began in 1958, the momentum for its destruction and for the federal urban renewal program itself began 20 years earlier, in the aftermath of the Great Depression. The Housing Act of 1949 would later mark the official birth of the federal Urban Renewal Program. Although it aimed to revitalize struggling inner cities, it often did so at the expense of established communities and displaced residents.

The West End of Boston was irretrievably changed in the mid-20th century when most of the neighborhood was eliminated in what is probably the best-known urban renewal project in the city. Although demolition began in 1958, the momentum for this destruction and for the federal urban renewal program itself began 20 years earlier.

The urban landscape of the United States in the mid-20th century was marked by a stark contrast. While gleaming skyscrapers rose in central business districts, many inner-city neighborhoods suffered from overcrowding, dilapidated housing, and inadequate infrastructure. These areas, often labeled “slums,” were seen as breeding grounds for poverty, crime, and social unrest. It was in this context that the US federal government embarked on a grand experiment – the Urban Renewal Program.

The seeds of urban renewal, however, were sown in the aftermath of the Great Depression. The Housing Act of 1937, a cornerstone of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, introduced the idea of federal intervention in housing. This act provided modest funding for public housing construction but also included a provision for so-called slum clearance. Despite the breadth of the New Deal, the scale of these early efforts at slum clearance was actually quite limited and locally controlled, virtually guaranteeing that housing projects would remain racially segregated.

This would all change following World War II, when the nation grappled with a different set of challenges. A booming economy fueled a mass exodus from rural areas to cities. Many migrants, particularly African Americans seeking opportunities in the North, settled in aging inner-city neighborhoods. Some neighborhoods, already struggling with overcrowding, were overwhelmed by the influx. Housing shortages became acute, and existing infrastructure strained. This influx, however, couldn’t counter the outflow of residents. For example, since 1920, population growth in most of the nation’s great urban centers had slowed from the previous century’s breathtaking pace to a crawl, and during the 1930s some cities – notably, Philadelphia, Cleveland, St Louis, and Boston – even lost population. Affluent urban dwellers were defecting to the suburbs, which threatened to undermine the downtown commercial districts and the posh residential areas which depended upon them.

Public anxiety about these “blighted” areas (or “slums”) fueled support for a more comprehensive approach. Reformers, planners, and politicians envisioned urban renewal as a chance to modernize cities. The idea was to clear slum dwellings, often deemed unfit for habitation, and replace them with modern, high-rise public housing, commercial developments, and transportation infrastructure. Proponents believed this would not only improve the physical environment but also foster social and economic revitalization.

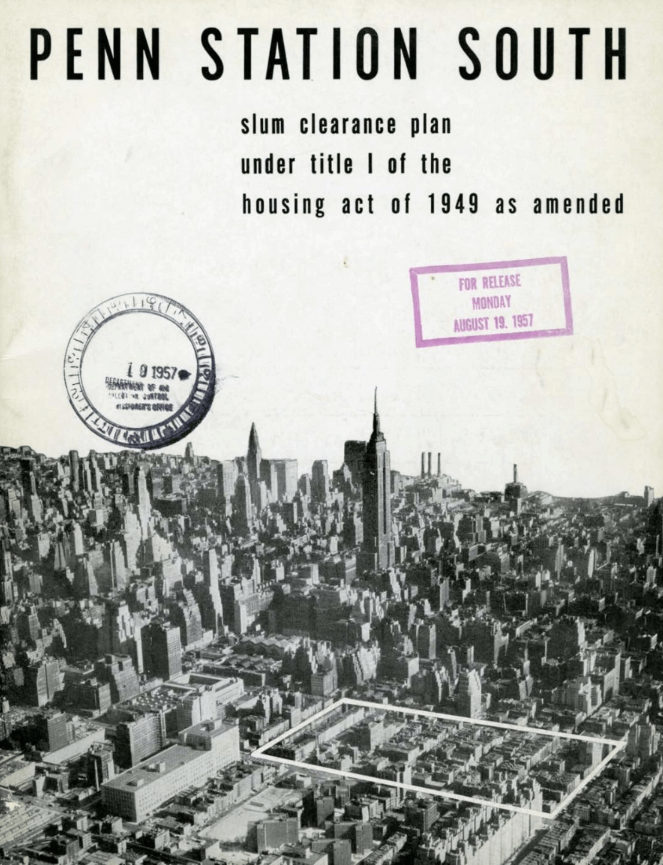

The Housing Act of 1949 marked the official birth of the federal Urban Renewal Program. This act established the Title I program, which provided federal grants to local governments for slum clearance and redevelopment. The act defined “slum” broadly, encompassing areas with overcrowded and unsanitary housing, inadequate light and ventilation, and deficient public facilities.

The 1949 act empowered local agencies, known as Local Housing Authorities (LHAs), to acquire land through eminent domain. This meant that the government could forcibly purchase properties deemed necessary for redevelopment, often displacing residents in the process. While relocation assistance was mandated, it was often inadequate or non-existent, leaving many displaced families worse off.

The 1954 Housing Act further expanded the scope of urban renewal. It introduced Title I clearance projects, which focused solely on demolition and land acquisition. This act also prioritized the use of cleared land for non-residential purposes, such as commercial development and public institutions. This shift in focus reflected a growing belief in the power of urban renewal to spur economic growth.

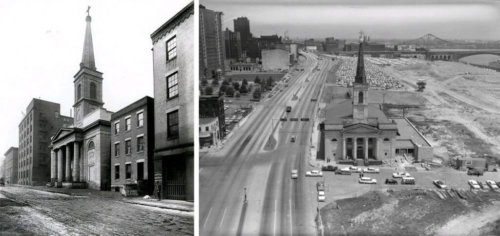

The early years of the program saw a surge in activity. Cities across the nation embarked on ambitious redevelopment projects. Iconic landmarks like Boston’s Government Center and St. Louis’ Gateway Arch were products of this era. Less iconic but still enormous, the West End was one of these early projects.

However, the program’s legacy is far from simple. While some argue that urban renewal improved living conditions for some residents by replacing dilapidated housing with modern apartments, the program faced significant criticism. The large-scale demolition of buildings often resulted in the destruction of vibrant, established communities, many with housing stock in livable condition. For example, urbanist Jane Jacobs encountered architects assigned to the destruction of the West End. A photographer member of the architects’ team was having a terrible time finding negative conditions to photograph. One told her “that on the whole the district’s stock of buildings was so well constructed it was superior to what would undoubtedly be erected in its place.”

The displacement of residents, primarily low-income and minority families, led to social disruption and a decline in affordable housing options. Critics pointed out the racialized nature of urban renewal. Many targeted neighborhoods in urban renewal projects across the country were predominantly African American, and the program exacerbated racial segregation by displacing residents and making it harder for them to find affordable housing elsewhere. The focus on commercial development over affordable housing further marginalized low-income communities. In the West End, decades of declining population contradicted the overcrowding justification for the neighborhood’s destruction. Clearly, other, less-noble goals were at play.

By the late 1960s, the negative impacts of urban renewal became increasingly apparent. The promised economic benefits often failed to materialize, and many cleared areas remained vacant for years. For example, of 37,200 acres cleared between 1949 and 1967, only 17,400 had been, or were in the process of being, redeveloped. Mounting social unrest and vocal community opposition led to a decline in public support. The 1970 Housing and Urban Development Act signaled a shift in federal policy. While not completely abandoning the concept of urban renewal, the act placed greater emphasis on neighborhood preservation and resident participation in redevelopment plans. The federal funding for urban renewal programs eventually dried up by the mid-1970s.

The legacy of the US Federal Urban Renewal Program remains complex. While it aimed to revitalize struggling inner cities, it often did so at the expense of established communities and displaced residents. The program serves as a reminder of the potential pitfalls of top-down, large-scale redevelopment projects and the importance of considering social and community needs in urban planning.

Article by Daniel Spiess, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: The Failure of Urban Renewal; Alexander von Hoffman, “The lost history of urban renewal,” Journal of Urbanism 1, no. 3: 282; Housing Act (Wagner-Steagall Act), Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston, 1937; National Commission on Urban Problems, Building America’s Cities (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1969), 165-69; Renewing Urban Renewal, The Nation, June 3, 2002.

1 Comment