The Mattapan Project: Urban Renewal That Never Happened

The Mattapan Project was first mentioned by the Boston Housing Authority in 1952 and later by the Boston Redevelopment Authority in 1962 as a possible urban renewal project. Despite the preliminary planning funding being granted in 1963 and the urban renewal application prepared in 1964, the project was dropped by the City of Boston. By the end of the 1950s, both the New York Streets and the West End had been almost completely demolished, yet Mattapan survived. The delays in the Mattapan Project’s site development and the eventual abandonment of the plan helps to demonstrate the changes in public opinion on urban renewal projects of the time.

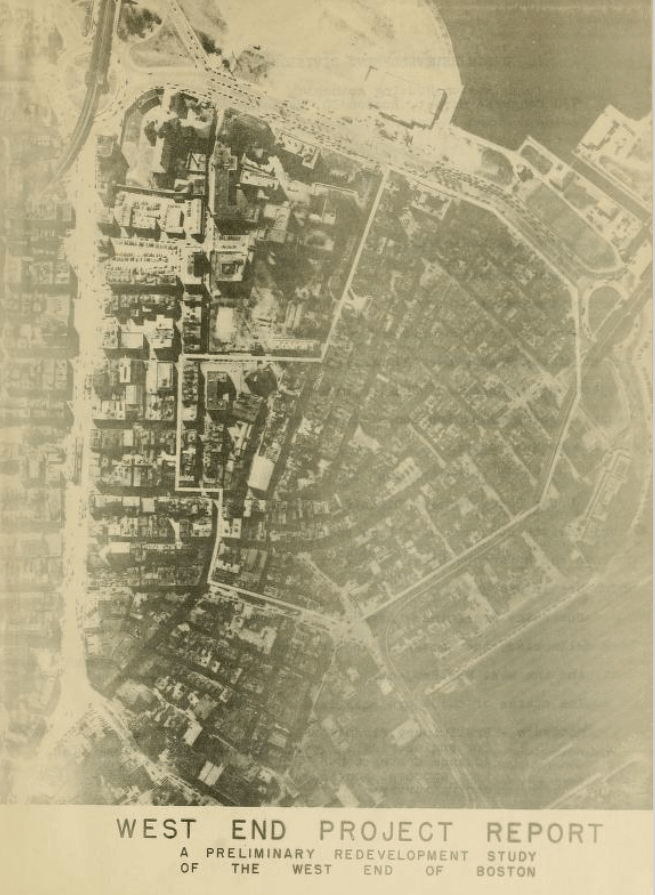

In early 1953, the Urban Renewal Division of the Boston Housing Authority submitted “The West End Project Report: A Redevelopment Study” to the Authority as their submission to the federal government for Urban Renewal funding. Ultimately, this funding was responsible for the destruction of the then-existing and very vibrant West End neighborhood.

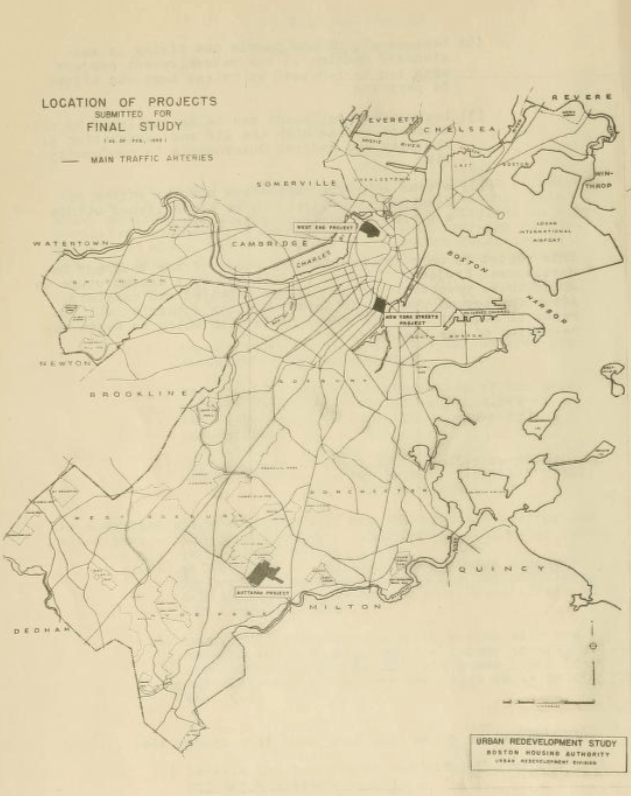

In the introduction of the report was a very brief mention of two other projects that were submitted at the same time as the West End Project: the New York Streets Project (in the South End) and the Mattapan Project. The status of those projects at that time was as follows:

Mattapan – Preliminary Planning Studies completed except for engineering surveys; Application for Final Advance Contract has been submitted to Washington; approval contingent upon results of engineering surveys;

New York Streets Project – Preliminary Planning Studies completed; Application for Final Advance contract approved by Washington;

West End Project – Preliminary Planning Studies completed; Application for Final Advance contract ready for submission to Washington.

Notably, the language that ended this introduction of these three projects clearly represents the top-down decision making process that left out any public participation and doomed the West End:

You will be pleased to know that this Division has received wholehearted cooperation and assistance from many City departments, such as the Planning Board, School Department and the Department of School Buildings, the Police Department, divisions of the Public Works Department, the Assessing Department, and the Board of Real Estate Commissioners, as well as the private utility companies and other private agencies.

The New York Streets Project, although smaller in total size than the West End, was similar in its method of mass clearance of existing, small-scale streets and historic buildings. The results of that urban renewal funding can be seen along Herald Street and the high-rise apartment buildings of the newly-coined Ink Block. The Mattapan Project, however, never happened.

The Project was to be located on a 42.5 acre parcel of land at the intersection of Cummins Highway and Livermore Street, about the size of the Boston Common. The parcel was marshland and ledge and was, for a long time, considered unbuildable due to the swampy conditions. At the time of the Mattapan Project proposal, there was the added concern that the parcel was becoming a “dumping ground for abandoned cars, cast-off furniture, and assorted trash,” according to a 1962 BRA report. The land was also apparently so unattractive for private development that between 1927 and the late 1950s, only three new single family houses had been built on the site, despite a post World War II building boom almost everywhere else in the city of Boston.

By the end of the 1950s, the destruction of both the New York Streets and the West End was mostly complete. Mattapan, however, had yet to begin. For unknown reasons, it appears that public and private consolidation of the Mattapan Project parcel could not be agreed upon and in 1953 the City of Boston withdrew its portion of the parcel for sale. The federal government, therefore, could not provide urban renewal funding for Mattapan without a unified parcel.

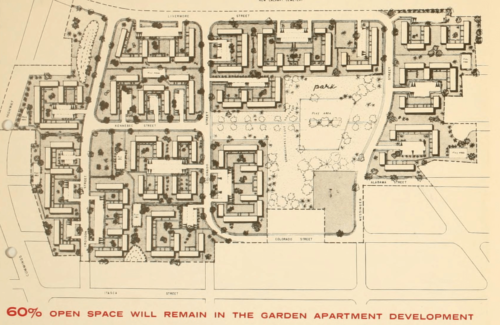

While Mattapan was delayed, urban renewal was beginning to react and change in the face of growing public outcry to autocratic destruction. A promotional piece from 1962 began to tell the story of moderation, inclusion, and community benefits of the proposed Mattapan Project that was finally getting started. The Mattapan Project touted in this brochure was to be 400 units of middle-income rental housing in approximately 40 two-story buildings. These garden-type apartments would rent between $115 and $150 per month. The Project was also to include plentiful open space, a new elementary school, and over $100,000 per year in new tax revenue to the city’s coffers. While these benefits were somewhat standard for early urban renewal projects, the clearly stated affordable rents hint at the increased community-oriented leaning of urban renewal. Additional language talks about improved “human values and living conditions,” “garden apartments harmonizing with the existing neighborhood,” and “maintaining the essential character and quality of the surrounding community.”

Community-oriented language was only the beginning. The biggest difference between the Mattapan Project and its earlier sister projects was the 1962 report’s almost-apologetic tone for taking property and evicting residents. The rhetorical divergence from earlier urban renewal projects is remarkable:

SOME HOUSES TO BE ACQUIRED

To make the development feasible and provide maximum benefits to the surrounding community, some 20 residential structures in the 42 1/2-acre site will have to be acquired. (All people potentially affected have been contacted.)

TAKINGS REDUCED TO A MINIMUM

Preliminary plans for the proposed development were redrawn many times to insure that every effort and ingenuity were applied to reduce takings to the absolute minimum.

SOUND STRUCTURES WILL BE MOVED

In every case where physically possible and where the owner desires, sound structures will be moved into an area adjoining nearby single-family development and adjacent to the proposed new park.

SPECIAL FINANCIAL PROVISIONS AND ASSISTANCE

Where houses cannot be moved, fair market value will be paid. Relocation expenses will also be paid (to both home owners and tenants). In addition, low-downpayment and long-term mortgage provisions are available to owners or tenants wishing to purchase other homes. Expert assistance will be provided in helping to locate the best and soundest values.

FULL-TIME RELOCATION ASSISTANCE

In this instance — as in every instance where relocation is necessary — the Redevelopment Authority believes that it owes special consideration and special obligation to those affected. In fulfillment of that obligation, a full-time relocation staff will be assigned to work with every family affected, to consider their problems individually, to assist them, to guide them, and to stay with them until all are relocated in decent, safe and sanitary housing at prices or rentals they can afford.

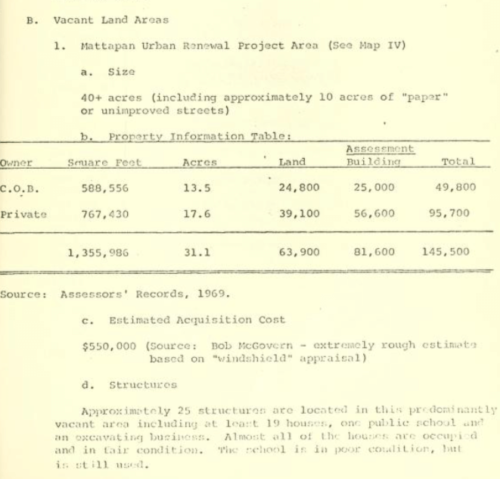

The glossy, hopeful, and accommodating project from 1962 never got built. A 1969 Boston Redevelopment Authority Planning Department study of Mattapan revisited the urban renewal project area. The site was still mostly vacant, except for about 19 homes, an old public school, and an excavation business. There was private interest in developing 112 housing units on a small part of the site. The BRA advised against this proposal but was not against development on this site, in general: they recommended 500 units of housing and a school complex (an “educational park”). None of this was built either except for a new elementary school.

The proposed Mattapan Project area remains mostly protected open space today. Despite the preliminary planning funding being granted by the federal government in 1963 and the urban renewal application prepared in 1964, the project was dropped by the City of Boston. Lack of continued city interest and community opposition have been cited as reasons for dropping the 42-acre renewal project plan. The delays in the site development, however, are a great example of the very quick change in public opinion of urban renewal projects of the time. Top-down government bulldozing, literal and figurative, gave way to preservation of community character, compensation, fairness, and public involvement.

Article by Daniel Spiess, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Boston Globe, “Boston’s vanished New York Streets: What the strange name of a long-gone neighborhood reveals about the city’s changing ambitions,” August 19, 2012; Boston Housing Authority, “The West End Project Report: A Redevelopment Study,” 1953; Boston Redevelopment Authority, “Urban Renewal in Mattapan,” 1962; Boston Redevelopment Planning Department, “Mattapan Study,” 1969.