Rum, Molasses, and Slavery in Boston

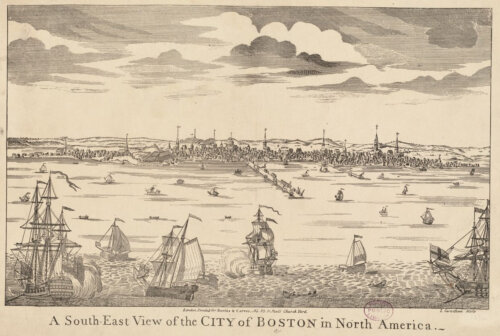

Boston’s rapid development in the seventeenth century would not have been possible without the labor of enslaved Africans, which allowed the construction of an integrated political economy linked primarily to markets of the West Indies. Boston served as a center of the slave trade and port of entry for enslaved Africans. By the early 1700s, the New England Colonies were deeply involved in an economic alliance with the sugar-producing West Indies, driven by the abduction and enslavement of Africans and the trade of raw materials, molasses, and rum.

In July 1637, Captain William Peirce sailed the Desire from Massachusetts to the western Caribbean, where he sold native Massachusetts Pequot captives in exchange for cotton, tobacco, and enslaved Africans. Colonists had begun enslaving Native people in and around Boston beginning in the 1620s. During the Pequot War (1636-1638) and King Philip’s War (1675-1676), captured Native Americans were forced into labor locally or trafficked for trade.

In February 1638, the Desire returned to Boston carrying the first recorded arrival of enslaved Africans into the northern English colonies. Three years later, in 1641, Massachusetts became the first English colony in North America to legalize slavery. By 1700, there were over a thousand enslaved Natives and Africans in New England. Over the following six decades, the enslaved population grew drastically and became primarily African.

Rum & The West Indies

Boston and Massachusetts served as a center of the slave trade and port of entry for enslaved Africans. By the early 18th century, all of the colonies of New England were involved in an economic alliance with the sugar-producing West Indies, driven by the abduction and enslavement of Africans and the trade of raw materials, molasses, and rum.

Rum, a distilled alcoholic beverage derived from the waste products of sugar, was first created on the island of Barbados in the mid-seventeenth century. Barbados was first colonized by the English in 1627, and by the mid-1640s, there were approximately 25,000 Africans; 8,300 planters of cash crops, including sugar cane; and at least 20,000 other European-descended people, mostly indentured servants, who tended the crops.

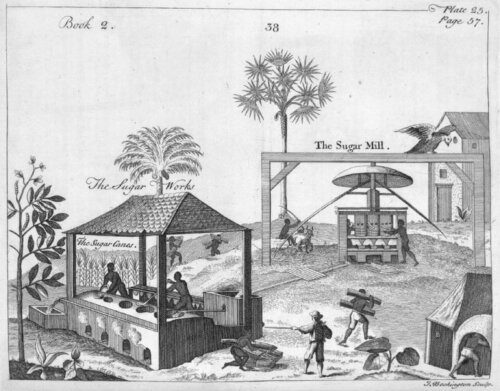

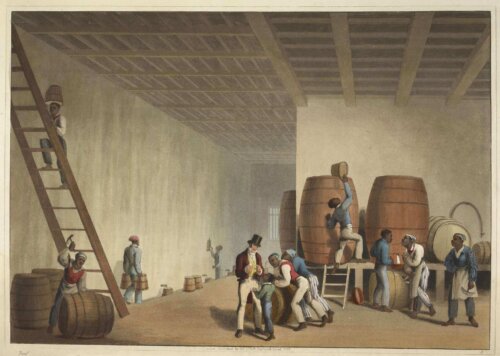

The first spirits derived from Barbados sugar cane were a result of the convergence of Amerindian, African, and European knowledge of fermentation. Plantation owners soon realized that there was profit not only in sugar, but in distilling the by-product of sugar production, molasses, into rum. By the 1650s, rum production was a crucial part of the work of sugar plantations. By 1660, Africans constituted the majority of the population of the island and historical records suggest that the majority of rum producers were enslaved men of African descent. By 1700, rum emerged as a major commodity that could be produced not only on tropical plantations, but throughout the Atlantic world.

Boston in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Because Barbados and other Caribbean islands were export plantation economies with limited land, they did not use valuable soil for planting food crops. The islands needed to feed the growing population; they additionally needed made goods, lumber, and livestock. There was also an unlimited need for slave labor: the plantation production of sugar was so deadly that the life expectancy of an enslaved worker was fewer than ten years after arrival.

Merchants, fishers, and farmers in the New England colonies recognized this need and Boston established itself as the primary port in the shipping trade with the islands. Cod, rejected by both the local and European markets, was an especially lucrative export and became the staple food fed to plantation laborers. In fact, “West India” became the commercial name for the lowest quality salt cod.

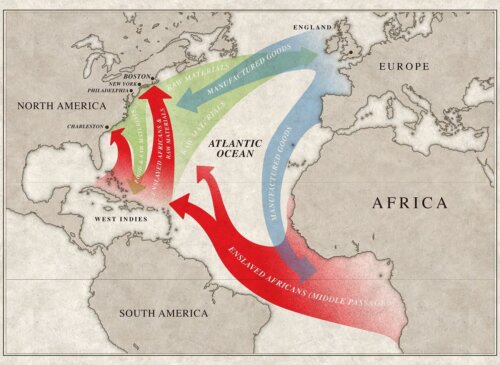

In the mid-1600s, merchants began to send ships to West Africa with products such as barrel staves and gunpowder which they traded at the Canary Islands for wine, sugar, and salt. These commodities were then traded for African captives at slave trading “factories” such as Elmina or Cape Coast Castle. The captives, many of whom did not speak the same language (purposeful on the part of slave traders), were crammed into ships and transported for approximately 80 days to the plantations of the Caribbean islands. Those who survived the treacherous voyage were exchanged for sugar, molasses, and rum to be brought back to New England. A little over 50 years after the first voyages from Boston Harbor to the African coast, Boston became the major port in North America for the trafficking of slaves.

A 1673 history of Barbados described the sales of slaves off New England ships:

When they are come to us, the Planters buy them out of the Ship, where they find them stark naked, and therefore cannot be deceived in any outward infirmity. They choose them as they do Horses in a Market; the strongest, youtfullest, and most beautiful, yield the greatest prices. Thirty pound sterling is a price for the best man Negro; and twenty five, twenty six, or twenty seven for a Woman.

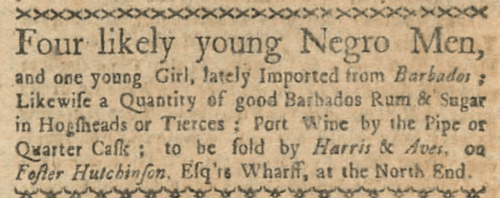

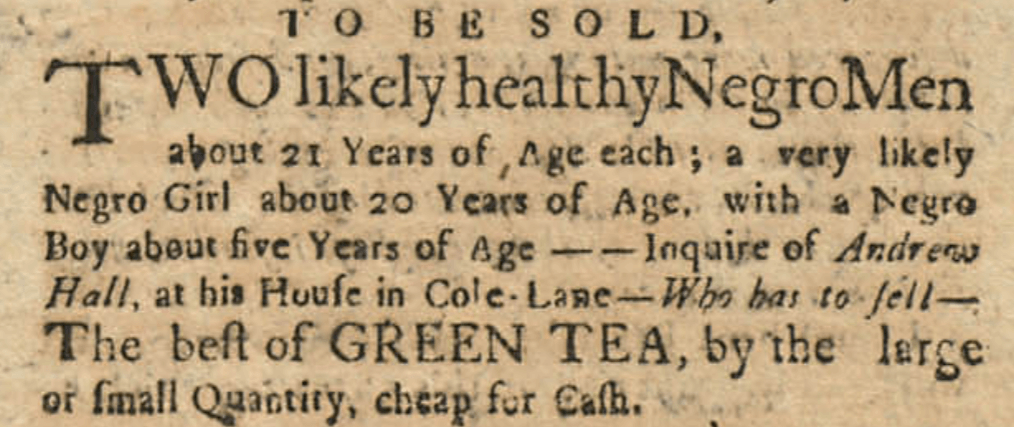

Slaves who went unsold would be taken to buyers in the North American colonies; some arrived in Boston and became the property of households or craftsmen. By 1720, approximately 12% of the city’s population was enslaved and nearly a quarter of all estates probated between 1700 and 1775 listed enslaved people as property. Up until the 1780s, prominent families such as the Faneuils, Belchers, and Royalls as well as less wealthy farmers and merchants sold and purchased 2,500 persons of African descent through Boston newspaper advertisements.

Boston Distilleries

Distilling had existed in North America since England’s earliest settlements in the area, but the enterprise focused predominantly on grain- and fruit-based spirits. Early distilleries were small, home-based endeavors. Boston’s first licensed distiller was William Toy who was “admitted as a Townsman” in March of 1642 and received a distiller’s license in 1646. By the 1660s, increasing trade with the islands encouraged the expansion of Massachusetts’ distilling industry and the invention of New England rum.

In the 1670s, more Boston distillers had moved their businesses from homes into single-purpose rum distilleries, mostly along the harbor. These small businesses, which had typically relied on family labor and usually that of women, began to purchase slaves to produce the rum. In the final years of the 1600s, as distillery regulations were put into place, probate inventories of several Boston distillers listed slaves alongside distilling and brewing equipment. But they could not legally drink the spirits they labored over. In 1694, the General Assembly enacted legislation prohibiting members of the liquor trade to serve alcohol to servants and slaves. The law stated: “Any person who is or shall be licensed to be an inholder, taverner, common victualler, or retailer, shall suffer any apprentice, servant, or negro to sit drinking in his or her house, or to have any manner of drink there, otherwise than by special order or allowance of their respective masters, on pain of forfeiting the sum of ten shillings for every such offence.”

In 1700, New England was importing primarily sugar and molasses from the West Indies and leaving the rum. Boston rum would now supply domestic and foreign markets and rum producers became directly involved in the slave trade. Low-grade cod to feed plantation labor continued to be the principal item of exchange. For the next seven decades, ships originating in Boston Harbor would complete the cycle of domestic rum traded in West Africa for abducted Africans who were brought to the West Indies and used as currency to purchase molasses, which would then be used to produce more Boston rum.

In 1750, there were 25 distilleries in Boston; by 1770 there were 36 and 51 in Massachusetts. The colony produced more than 40% of the total rum distilled in North America, more than 2 million gallons in a year.

Boston’s West End

From the early 18th century, the area of the West End, first known as New Fields and later West Boston, was noted for ropewalks, sugar refineries, and several distilleries. From 1682 to 1784, Chardon Street was called “the highway to Jackson’s distil house.” From 1715 until 1786, Bowker Street at Chardon Street was called “Distill-House Square” or “Distillers Square.” Cambridge Street, named in 1708, was the address of several distilleries and multiple West India Goods shops. The popular shops sold molasses, rum, spices, textiles, tea, and wine. Close to Distill-House Square, on Cole Lane, Andrew Hall posted an advertisement for the sale of enslaved people in The Boston Gazette in 1766 (pictured below).

Molasses & Rum in Boston’s Culture

Before Caribbean sugar plantations began to transform Atlantic market trade, sugar imported from England was a valued commodity among colonists in Massachusetts. For colonies short on coinage, payments in sugar were not unusual. In fact, between 1650 and 1656, 16 students paid their Harvard College tuition or room and board in sugar.

When molasses, a by-product extracted during the sugar refining process, became easily available through trade with the West Indies, New Englanders grew fond of the less expensive sweetener and it quickly became a staple food. Molasses was considered a nutritious food, an important recipe ingredient, and even a cure for ailments. (In a “full circle” prescription, a molasses enema was recommended for the “dry gripes,” a painful condition thought to be caused by the lead pipes used in the distillation of rum.) It is estimated that each colonist was consuming three quarts a year in the early 1700s, not including the molasses consumed as the main component of rum.

In the 1730s, the consumption of rum in the American colonies averaged 3.75 U.S. gallons per person annually. “Rum” after 1700 typically referred to the domestically-produced (likely in New England) drink – a low-priced, low-quality version of the drink imported from the Caribbean. As Boston grew and it was more costly to run a distillery in town, Watertown, Haverhill, Charlestown, Salem, and Medford became home to thriving distilleries.

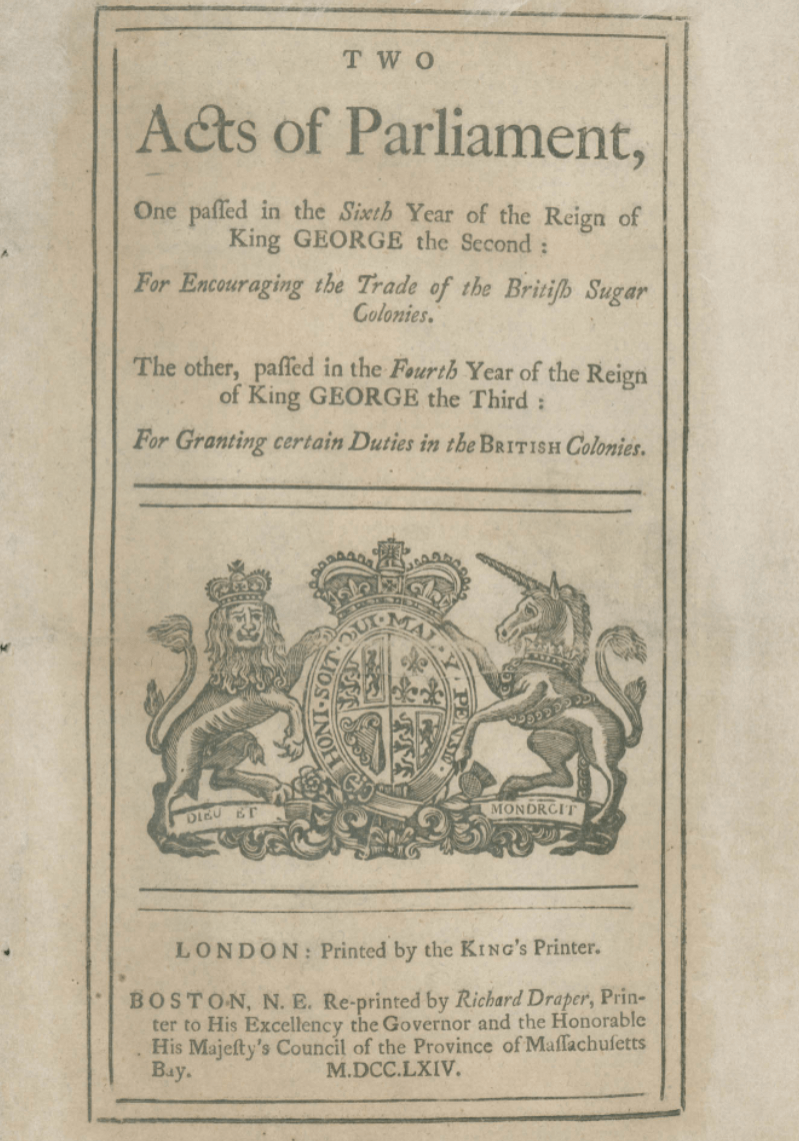

The Molasses Act & Sugar Act

As the Colonies became more economically stable and successful, Britain predicted that they would try to break free of the Crown (though surmised that they would ultimately fail). The Molasses Act of 1733 was Britain’s attempt to reassert its colonial rule. The Act imposed such heavy import duties on molasses from the non-British Caribbean islands that it should have greatly diminished the trade, which would have also impacted the rum and cod export economies. That is, if the taxes had actually been paid. The sugar plantations on the French possessions of Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Saint Domingue were happy to accommodate New England’s demand for molasses, which the British islands alone could never have satisfied. And for much less than the cost of import duties, customs officers could be paid off to declare molasses imports were from Barbados or Jamaica rather than the French islands. The trade continued to be lucrative through contraband.

The solution to the failure of the poorly enforced Molasses Act came in 1764 with the American Duties Act, known as the Sugar Act, which imposed duties on sugar, cloth, indigo, coffee, and Madeira wine (the Madeira duty an attempt to make colonists switch to port from British merchants). This Act would be enforced by the British navy who had the power to seize ships attempting to avoid paying taxes.

The newly enforced tariffs were viewed as a great injustice and northern colonies joined together to petition to repeal the Act by convincing Parliament of the integral role that cheap imported molasses played in the health of England’s own economy. After all, without an abundance of molasses, northern rum distilleries would fail; without the substantial income from rum, colonies would purchase fewer manufactured goods from England and begin making more of their own.

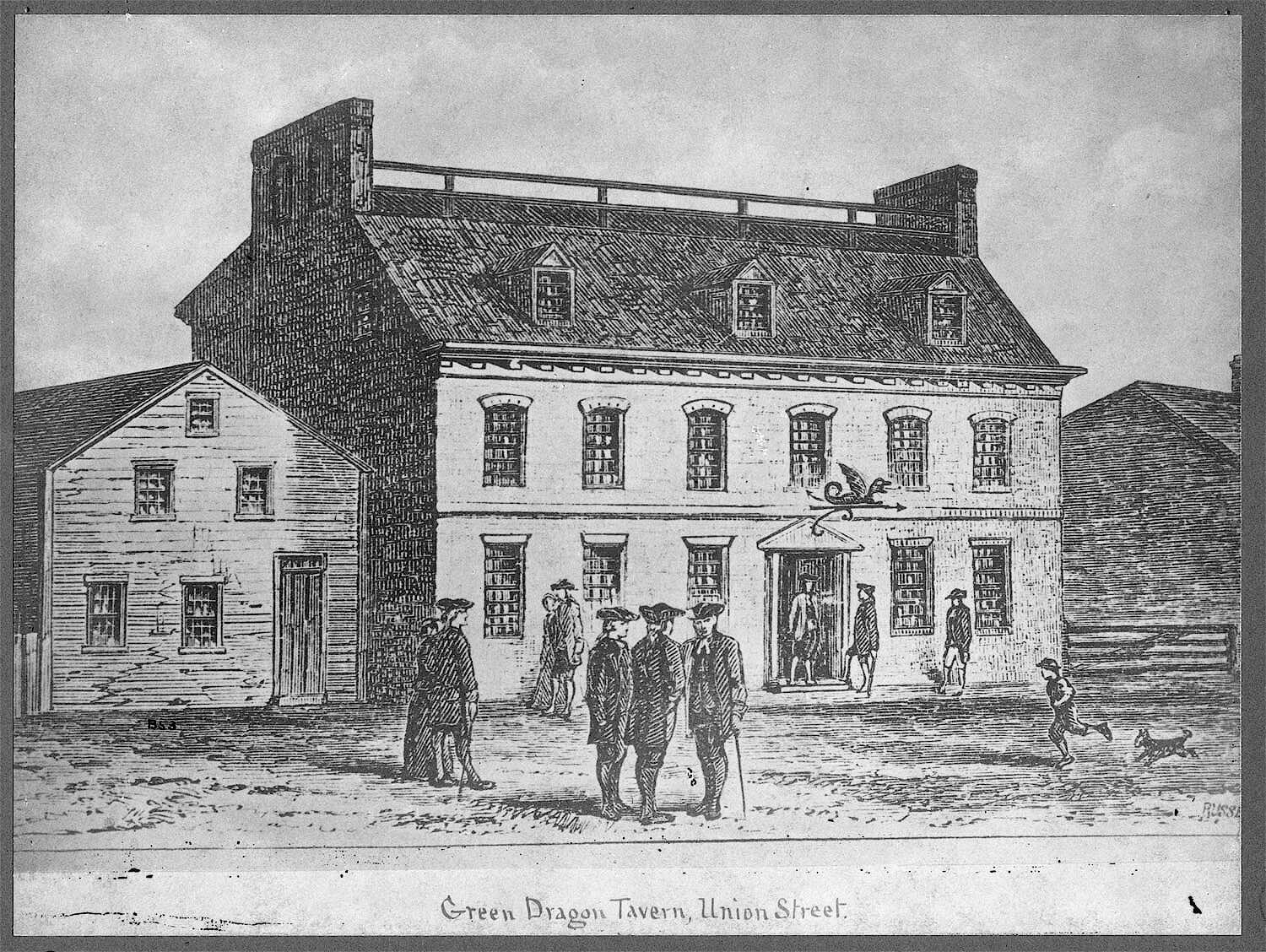

Colonial arguments prevailed and the Sugar Act was revised in 1766. It was the beginning of the American colonies successfully organizing to resist British meddling. When the Crown asserted its right to impose other taxes with a tax on imported tea and the Stamp Act one year later, the colonies had some experience in collective resistance. Rum-serving taverns were central to this political and armed resistance. In 1769, there were 90 licensed taverns in Boston; of these, 20 license holders were members of the Sons of Liberty, the rebel group behind the Boston Tea Party.

Decline of the Rum Trade

The peak of Boston’s shipping activity tied to the rum trade and the sale of enslaved people occurred between 1740 and 1769. In the years leading up to the American Revolution, rum constituted 20% of Massachusetts’ economy. The same Boston society that demanded independence and freedom from British tyranny continued to grow its wealth by providing Caribbean plantation owners with cod to keep enslaved people producing the sugar and molasses that this economy relied upon. Later, when New England was barred from trading cod with the British West Indies, tens of thousands of people enslaved on plantations died of hunger.

Some New Englanders did speak out about the hypocrisy in fighting for freedom while accepting slavery at home and fueling the transatlantic slave trade. White critics of slavery became more vocal about the Rights of Humanity. Black Bostonians, free and enslaved, became participants in the changing political landscape by organizing and taking part in protests and demonstrations. Between 1773 and 1777, Black Bostonians petitioned the colonial and revolutionary governments for their freedom seven times.

The practice of legal slavery in Massachusetts was ended gradually through case law and the institution was abolished in 1783 with the Commonwealth v. Jennison decision that declared slavery incompatible with the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution.

During and following the Revolutionary War, rum distillers lost many of their molasses sources and the market collapsed. Whiskey made with wheat grown in North America, and often distilled with the expertise of Irish and Scottish immigrants, largely replaced rum.

After Massachusetts abolished slavery, Boston became known as a safe haven for freedom-seeking slaves. The north slope of Beacon Hill (then the West End) became the center of the abolitionist movement in the city, and an important site on the Underground Railroad, particularly in response to the federal Fugitive Slave Laws. More information about this period of West End history can be found HERE and in The West End Museum’s special exhibit “An Illusion of Freedom: Boston and the Fugitive Slave Laws,” running February 27th through June 1st, 2025.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Alex Bice, Sebastien Hardinger, Mahala Nyberg, Claire Tratnyek, Adam Tomasi, Shannon Webber, To Be Sold (April 21, 2020); City of Boston, Boston Slavery Exhibit; Dan Dain and Peter Vanderwarker, A History of Boston (Peter E. Randall Publisher, 2023); Samuel Adams Drake, Old Boston Taverns and Tavern Clubs (W.A. Butterfield, 1917); Equal Justice Initiative, “The Transatlantic Slave Trade”; Mark Peterson, The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865 (Princeton University Press, 2020); Stephen Puleo, Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 (Beacon Press, 2003); Massachusetts Historical Society, African Americans and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts; Nancy S. Seasholes, The Atlas of Boston History (The University of Chicago Press, 2019); National Parks Service, “The DESIRE and the Beginnings of the Massachusetts Slave Trade”; National Parks Service, “The Middle Passage”; Jordan B. Smith, The Invention of Rum: Creating the Quintessential Atlantic Commodity (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2025); Annie Haven Thwing, The Crooked and Narrow Streets of the Town of Boston, 1630-1822 (Singing Tree Press, 1970); Wendy Warren, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America (Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016).