The Fugitive Slave Laws in Boston: Part 1, 1641–1849

This article, part 1 in a two-part series, explores the documentary history of the legalization of slavery in the United States, and the creation of federal laws prioritizing the rights of slaveholders over basic human rights. Part 1 surveys Massachusetts’ legalization of slavery in 1641; its abolishment of slavery in 1783; the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793; and how abolitionist organizations in Boston defied the Fugitive Slave Laws in order to help escaped enslaved people defend their freedom.

Slavery had been a part of Massachusetts’ history since 1641, when it became the first of England’s colonies in North America to legalize slavery. However, resistance to slavery also had a long and storied history. For example, Belinda Sutton, a formerly enslaved woman at the Royall House in Medford, petitioned the court to give her a pension in recognition of her years of labor for her enslaver. Boston’s own Phillis Wheatly Peters, an enslaved and later emancipated poet, wrote in favor of the American Revolution and used her writing to help prove the abilities of Black people.

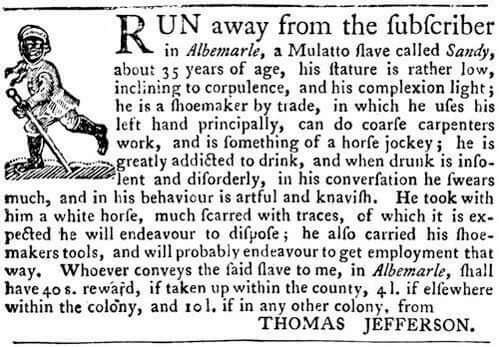

Over the years, the number of slaves in English North America grew dramatically, especially in the Southern colonies. A vast majority of enslaved people were Black people captured from Africa or brought from the West Indies. As the colonies formed into the United States, the new country embedded slavery into its founding documents and laws. Many enslaved people attempted to escape to Northern states that had outlawed slavery, while former owners did their best to hunt them down and bring them back to captivity.

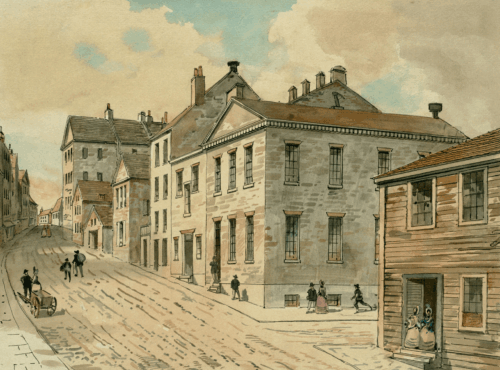

After Massachusetts officially abolished slavery in 1783, Boston became known as a safe haven for freedom-seeking enslaved people. The city’s active Black community on the North Slope of Beacon Hill (the historic West End) and members of its growing abolitionist movement provided protection and support to formerly enslaved people. Abolitionist minister Theodore Parker estimated that by 1850, 400 to 600 escaped slaves lived in the city. Among the Black organizations that supported self-emancipated Bostonians were the First African Meeting House on Joy Street and the Twelfth Baptist Church, also known as the Fugitive Slave Church.

Fearing the growing opposition to slavery in the country, and witnessing successful attempts to stop slave catchers, Southern slave-holding states sought more and more legal protection from the federal government. These protections would become known as Fugitive Slave Laws.

Slavery and the Constitution

Of the 55 authors of the Constitution of the United States, 25 were slaveholders, and they wove the rights of slave ownership into the fabric of the document. The Three-Fifths, Importation, and Slave Insurrection Clauses all guaranteed the continued legal enslavement of people and disproportionately increased the power of slave states in Congress.

Article IV, Section 2 of the Constitution also protected the right of a slave owner to recapture runaway slaves:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such service of labour may be due.

In other words, even if an enslaved person made their way to a free state, they could be legally hunted down and returned to their owner under the law of the land.

As they worked to perpetuate the rights of slaveholders, many founders recognized the racism and moral hypocrisy of their actions. James Madison, a slaveholder, said during the Constitutional Convention of June 1787: “We have seen the mere distinction of color made in the most enlightened period of time, a ground of the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.”

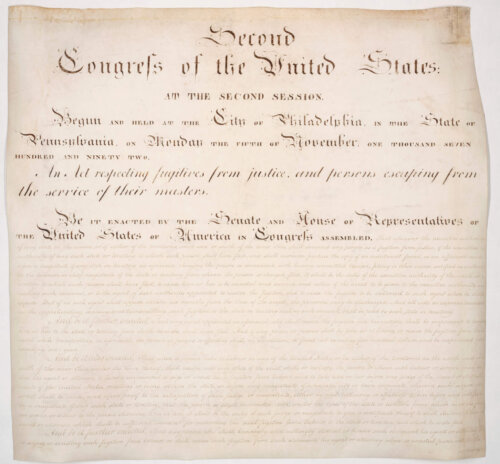

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

At the end of the 18th century, a growing number of Northern states began to abolish or limit slavery. Massachusetts abolished slavery in 1783 after a series of legal cases established that slavery was incompatible with the Massachusetts State Constitution of 1780. However, some people were kept under de facto slavery as indentured servants through the end of the century.

During the same period, Congress banned slavery north of the Ohio River (the Northwest Ordinance of 1787). Fearing these developments would encourage their enslaved people to flee, Southern states petitioned Congress for stronger legal protection. This request resulted in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, authorized and signed by President George Washington, a slave owner himself.

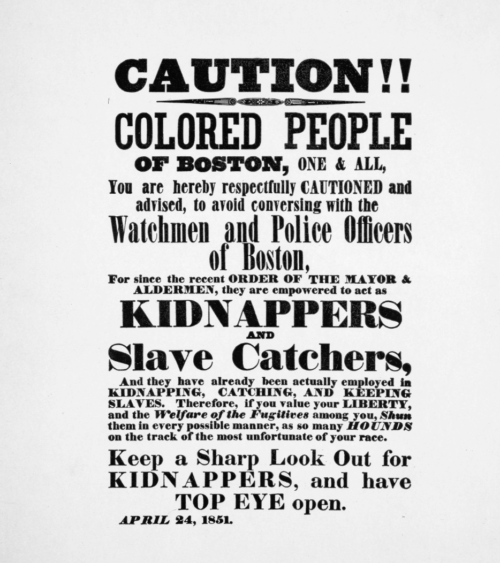

The new law clarified the states’ responsibilities with regard to handling escaped slaves, and provided more defined legal procedures for their capture and return. It read that anyone “who shall knowingly and willingly obstruct or hinder” the capture of a fugitive enslaved person or “rescue such fugitive from such claimant” could be fined up to $500 and receive a prison term of up to one year. It was therefore illegal, officially, to help enslaved people escape to freedom. Despite the threat of such penalties, many Bostonians continued to take part in risky actions aimed at protecting fugitive enslaved people from their captors.

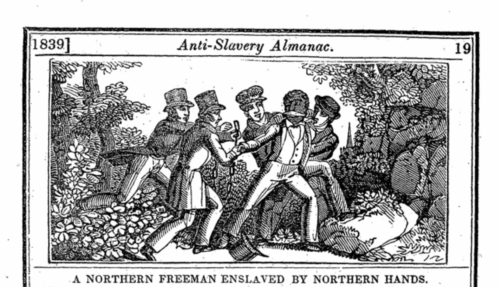

The Boston Abolition Riot of 1836

The event known as the Boston Abolition Riot began on Friday, July 30, 1836, when the ship Chickasaw, out of Baltimore, sailed into Boston harbor carrying two Black female passengers traveling under the names Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates (historians believe their real names were Anna Patten and Mary Pinckney). Soon after docking, Matthew Turner boarded the ship and asked Captain Henry Eldridge to detain the two women, who he claimed had escaped the service of his employer, John B. Morris. While Turner left to obtain a warrant to return Bates and Small to Baltimore, Eldridge moved the Chickasaw offshore.

Soon, a large number of Black Bostonians appeared at the wharf. Some rowed out to the ship and said they saw two women “making signals of distress to them from the cabin windows.” One Black man, Samuel H. Adams, obtained a court order from Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw requiring Eldridge to release Bates and Small into the custody of Deputy Sheriff Huggerford until a hearing was held. Huggerford held the women in the Leverett Street Jail (which stood near the site of The West End Museum) over the weekend, while members of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS) tended to them. Bates admitted to a member of the BFASS that she had in fact been enslaved by Morris, and had run for freedom because she suspected he planned to sell her.

The hearing opened on August 1, at 9 a.m., presided over by Judge Shaw at the Suffolk County Courthouse at Court Square. Abolitionist lawyer Samuel Eliot Sewall represented Bates and Small, while attorney A. H. Fiske spoke for Turner. A crowd of 200 to 300 spectators filled the courtroom, mostly Black supporters of the women, along with several white abolitionists. Though the case in question was Captain Eldridge’s right to detain the women, Fiske argued that the court should instead rule on Bates and Small’s return to Baltimore. In response, Sewall simply argued that the ship’s captain had no right to hold the women against their will, drawing applause from the onlookers. Judge Shaw thought for a short time, then seemed to announce that the women should be released, but the situation quickly escalated before he finished speaking.

The abolitionist newspaper The Liberator reported:

Under the mistaken impression that the words of the judge amounted to a discharge of the prisoners, and supposing that the claimant was about to make a fresh seizure on the spot, which might be intercepted, a general rush was made, prisoners and crowd together—down the stairs of, the, court house, at the door of which the prisoners entered.

Other newspapers reported that before the rush, people were heard to yell “take them” and “go, go,” and that during the scuffle “[a]n old colored woman, of great size,” caused Deputy Sheriff Huggerford minor injury while grabbing his neck and blocking him from the escaping women.

Once in the street, Bates and Small were put into an awaiting carriage that sped “up School Street, down Beacon Street, over the mill dam on Western Avenue, and, apparently, out of Boston.” A posse led by Huggerford chased the fleeing pair as far as Portland, Maine, but failed to catch them. It is believed that Bates and Small made it to Canada after their escape.

For the most part, newspapers of the day were highly critical of the Black spectators and abolitionists for what they called a lawless mob action and an insult to the workings of the American judicial system. William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator, accused the mainstream press of hypocrisy for trying to “embitter the prejudices against the poor colored people, by exaggerating their offense” while at the same time judging much more lightly the rioting of anti-abolitionists.

Despite the potential for legal penalties and pressure from even their fellow free state citizens, Black and white abolitionists did what they could to protest and defy Fugitive Slave Laws. Bostonians bravely worked to protect others’ natural right to freedom. Yet, as will be seen in Part Two of this article, opponents of freedom were also willing to push for their agenda. With the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, tensions rose and this violent collision of forces would lead to the breaking up of the Union and the Civil War.

Article by Bob Potenza and Jaydie Halperin, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Barbara F. Berenson, Boston and the Civil War: Hub of the Second Revolution (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014); Lyndsay Campbell, “The ‘Abolition Riot’ Redux: Voices, Processes,” The New England Quarterly 94, no. 1 (March 1, 2021): 7–46; James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999); J. Gordon Hylton, “Before There Were ‘Red’ and ‘Blue’ States, There Were ‘Free’ States and ‘Slave’ States,” Marquette University Law School, November 1, 2011; Jim Crow Museum, “Slavery in America – Timeline”; Leonard W. Levy, “The ‘Abolition Riot’: Boston’s First Slave Rescue,” The New England Quarterly 25, no. 1 (1952): 85–92; The Liberator, October 18, 1850; Library of Congress, “The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship”; Massachusetts Historical Society, “The Legal End of Slavery in Massachusetts”; Massachusetts Historical Society, “Timeline of Events Relating to the End of Slavery”; National Archives, “Missouri Compromise (1820)”; National Constitution Center, “Massachusetts Personal Liberty Act (1855)”; National Park Service, “Faneuil Hall, the Underground Railroad, and the Boston Vigilance Committees”; National Park Service, “The Fugitive Slave Laws and Boston”; National Women’s History Museum, “Phillis Wheatley”; Thomas H. O’Connor, Civil War Boston: Homefront & Battlefield (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999); Mark A. Peterson, The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865 (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2019); Report of the Boston Female Anti Slavery Society : with a concise statement of events, previous and subsequent to the annual meeting of 1835 (Boston: Published by the Society, 1836); Royall House & Slave Quarters, “Belinda Sutton and Her Petitions”; Smith Court Stories, “Museum of African American History.”