Uncovering Lindall Place

Tucked away in a cozy nook off Cambridge Street, on the border of the West End and Beacon Hill, tiny Lindall Place can easily be overlooked by passersby. The street is modest in size and camouflaged by the elevated Red Line tracks leading to Charles MGH Station from the Beacon Hill Tunnel . Yet, as can be seen in a previous article on Ridgeway Lane, Boston’s little byways often offer up some interesting stories, if one looks hard enough.

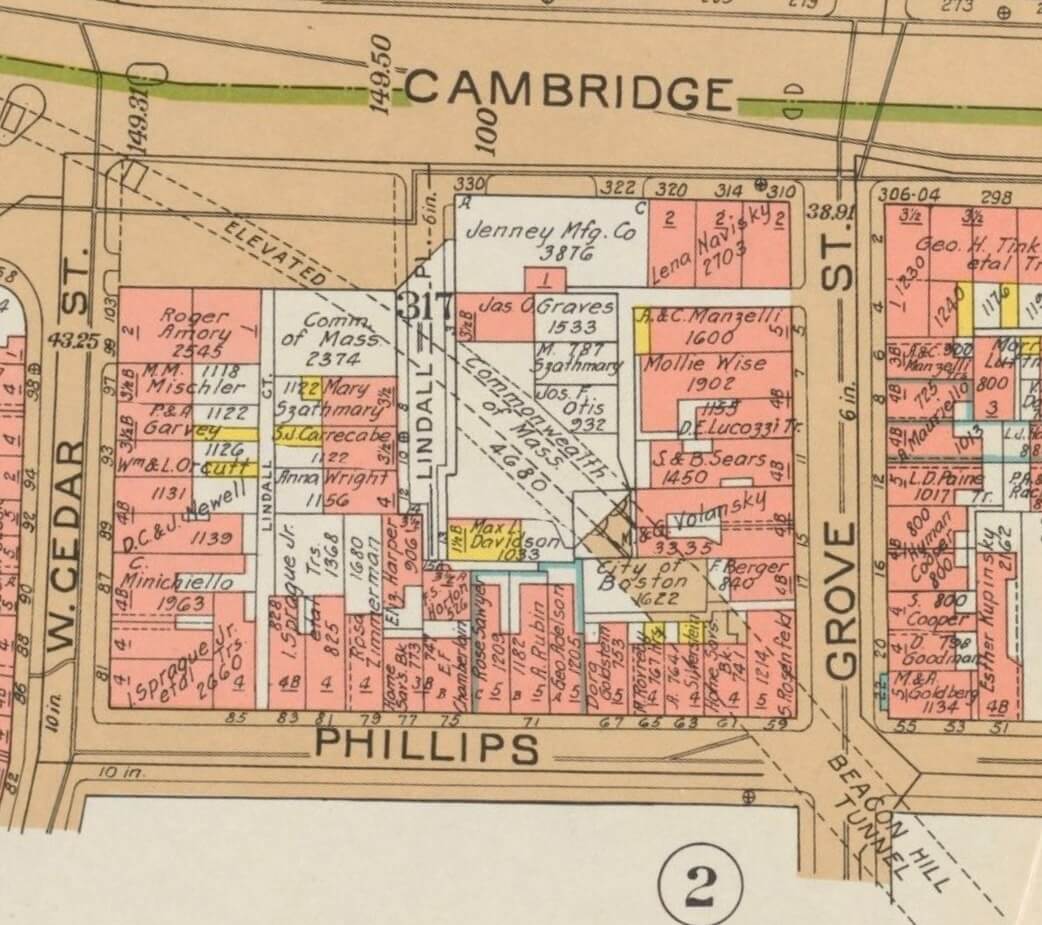

Lindall Place, first laid down in 1831, bears the name of one of the city’s oldest Puritan families. Sitting on former pasture land, at the time of its founding it was bounded by the banks of the Charles river, Cambridge Street, Grove Street and Pinckney Street. The lot was first recorded as the property of Samuel Cole, who then sold it to a butcher, Zachariah Phillips, in 1658. Phillips later passed the land over to Governor John Leverett, a substantial land owner in the West End. Lindall Place came into being during a great growth period in the Beacon Hill area. The iconic brownstone homes of the South Slope were beginning to rise, and Charles Street, the neighborhood’s future commercial artery, was formed from material made available from Beacon Hill’s leveling. Originally, Lindall Place was lined on both slides with modest three-story brick row homes.

The first news items concerning Lindall Place involved real estate transactions and petty crime. On September 20, 1873 the Boston Globe reported the theft of $42 (over $1,100 in today’s money) from Mrs. John L. Carter of 2 Lindall Place by unidentified thieves. Almost exactly one year later, someone stole a woman’s bag holding $40 worth of jewelry from the resident of 5 Lindall Place, Mary A. Mc Laughlin. Six years later, on October 8, 1879, Bertie Davis of 8 Lindall Place reported the theft of a $15 shawl. Future reports from Lindall Place shifted from robbery to those of personal injury. On the morning of New Years Day 1874, a team of horses on Cambridge Street struck poor Etta Proctor of 11 Lindall Place. Thankfully, she escaped with only minor injuries. On March 7, 1881, John Connors of 9 Lindall Place suffered a fractured leg. He had been “scuffling on Eliot street, [and] was thrown to the sidewalk.”

In May of 1881, Lindall Place resident Jolin H. Fennerty, described as having “an extraordinary long head”, filed for divorce from his wife, Winnifred (a.k.a. Mary Moseley). He complained that “she would stay out all night with bad men, and he soon found her to be a common night-walker.” More seriously, on June 7, 1889, the family of 13-year-old Mary C. Nute reported her missing. She had been last seen leaving home “wearing a straw hat with red trimmings and a white mother hubbard wrapper [a long, loose fitting house dress].” No official reports of her reappearance could be found, but mention of an actress named Mary C. Nute years later suggests that she was eventually found.

Two notable persons once made their homes at Lindall Place. William Smallwood, a poor Black man, lived in the “darkened” basement of 12 Lindall Place with his wife. He was reportedly the oldest surviving Civil War veteran at 109 years in 1925. Smallwood served with the storied 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Sources indicate that he was the only surviving member of the unit recorded on film. His great-grandfather, a free black man, was a valet for George Washington. Another figure was Prescott Townsend. He owned and lived at 15 Lindall Place and ran a tearoom at the rear-adjoining building at 75 Phillips Street. Townsend was a gay activist and self-described Bohemian from the 1920s until his death in 1973. He owned several properties and ran small businesses on Beacon Hill, including The Barn, a notorious bookstore, and a brothel called the Jolly Roger. He founded some of the first gay discussion groups and organizations in the city during the 1940s and 50s.

The most significant event affecting Lindall Place was the construction of the elevated train track leading into the Beacon Hill Tunnel. In December of 1909 the Boston Transit Authority approved plans for the Cambridge Subway running from Park Street Station to Harvard Square, Cambridge. This ambitious project required a tunnel running under Beacon Hill from Grove Street (next to Lindall Place), beneath the Boston Common to Park Street Station. A 150 foot long elevated track running across Lindall Place would connect the tunnel with the tracks running across the new West Boston Bridge (later the Longfellow Bridge) to Cambridge. The Boston Elevated Railway opened service on the new line on March 23, 1912, changing life on the small street forever. In 1932, the Massachusetts Transit Authority built Charles Street Station between the Longfellow Bridge and the elevated tracks at Lindall Place.

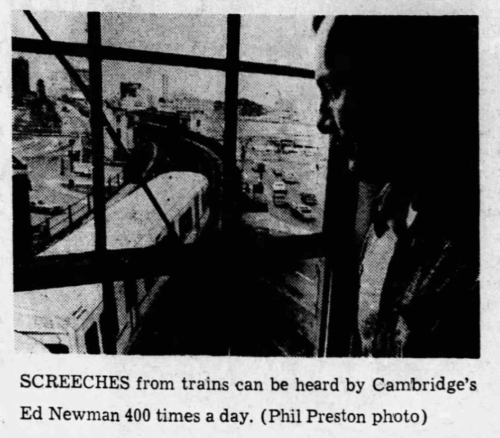

Since the construction of the elevated track, residents have had to endure the sight of this imposing length of steel looming above them. They had to listen to the “clackety-clack” sound of 400 trains passing each day. Ed Newman, a resident of 3 Lindall Place, observed in 1973 that “it looks like the train is going to plow right into the living room.” With his building close enough to the tracks to feel the vibrations, Newman said he no longer needed to mix his own cocktails. He could just place his glass “on the window sill and the MBTA does the rest.” Some neighbors could not bear the noise and eventually moved. Yet, Newman said many like him stayed because the rent at Lindall Place was so much lower compared to the rest of the neighborhood.

Lindall Place was also witness to dangerous train collisions. On August 1, 1975, three trains carrying 1,200 riders crashed in the Beacon Hill Tunnel, injuring 132 people. Onlookers from Lindall Place witnessed emergency workers assisting passengers down fire truck ladders propped against the elevated tracks.

Finally, in 2000, after years of the constant rattling of trains, the MBTA erected a sound wall along the tracks above Lindall Place. One long-time resident felt it made a great difference in the quality of life on the street. As modern images suggest, today’s residents of Lindall Place have made the most of this hidden oasis at the foot of Beacon Hill. Despite the continued presence of the hulking metal beam impairing their view, owners have maintained their properties to a high degree. For those attracted to this hidden and quirky location, Lindall Place offers a desirable, yet pricey place to live. A single unit in a building costing $8000 in 1873, sold for almost $1 million in 2023.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Emma, Beckman, “Prescott Townsend” (The West End Museum, June 18, 2024); Fergus M. Bordewich, “Civil War Veterans Come Alive in Audio and Video Recordings”, (Smithsonian Magazine, October 4, 2011); The Boston Globe, April 1, 1873, September 22, 1873, September 7, 1874, January 12, 1875, October 9, 1879, March 8, 1881, May 18, 1886, January 2, 1909, May 17, 1910, January 22, 1911, August 22, 1911, February 27, 1925, July 11, 1925, January 24, 1927, March 8 1930, March 27, 1931, January 19, 1934, April 16, 1973, August 2, 1975, January 11, 1998, May 14, 2000, July 9, 2023; City of Boston, “Records of Streets and Alleys”, 1910; G.D. Emerson, “The Beacon Hill Tunnel, How a Half-mile of the Boston Subway Was Built In Tunnel”, Scientific American, July 22, 1911; Annie Haven Thwing and D. Brenton Simons, The Crooked and Narrow Streets of Boston, (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2017).