Black Boston in the 1830s

The 1830s was a transformative decade for Boston’s Black community, characterized by the intersecting forces of burgeoning abolitionist activism and escalating urban segregation. This resulted in the growth and consolidation of the Black population in the West End on the North Slope of Beacon Hill.

In the wake of the American Revolution, Boston emerged as an appealing destination for many Black individuals. This was due in part to the abolishment of slavery in Massachusetts in 1783 and the perceived level of racial tolerance there. Those in the Black community began settling in the few areas open to them at the time: the North End; the West End, north of Cambridge Street; and the North Slope of Beacon Hill. At the time, all three of these districts were either remote, had a disreputable reputation, or were in decline before Black settlement.

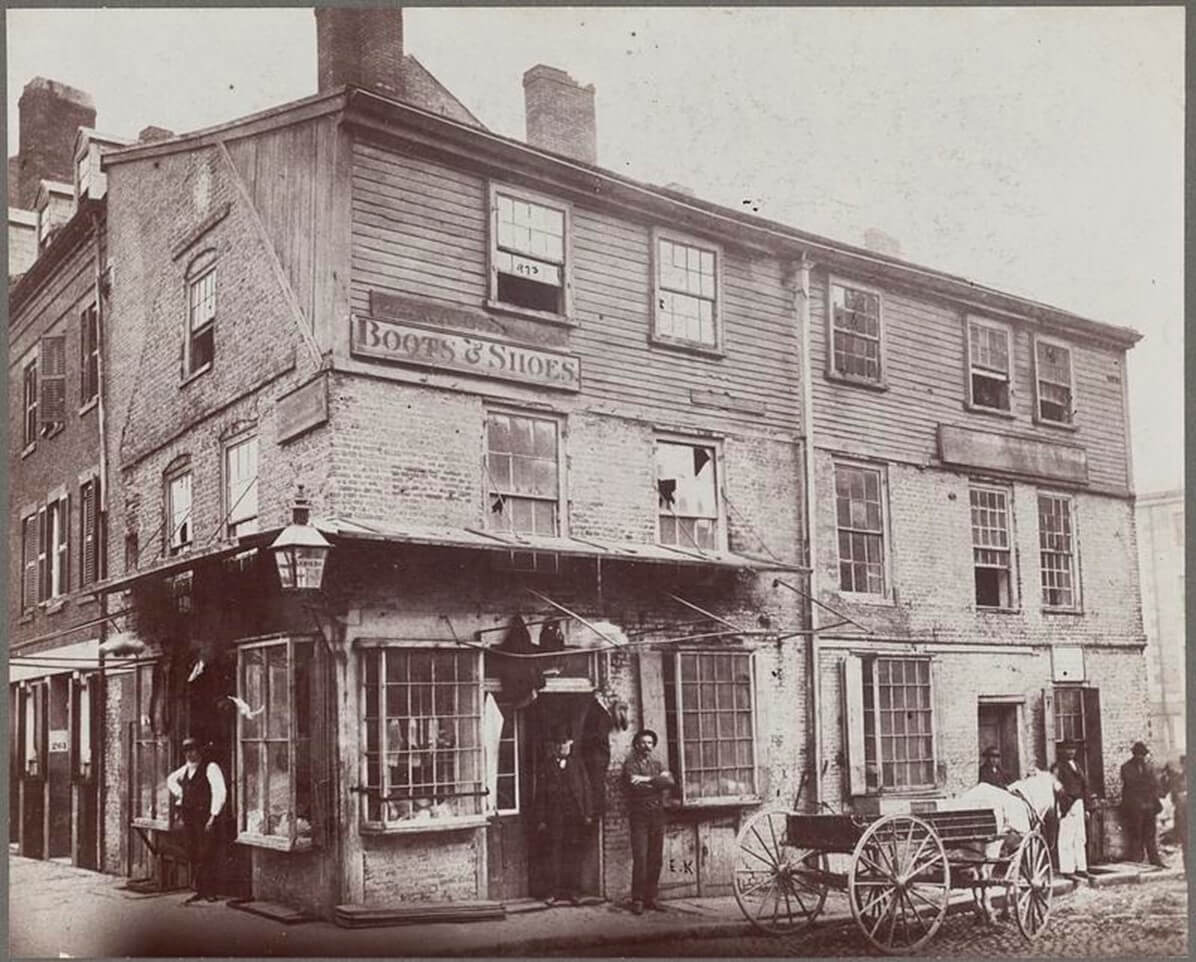

English settlers had established the North End as their first major neighborhood, but over time it became overcrowded and fell out of favor (especially among the wealthy). Until the 1830s, the North End was the largest area of Black settlement in Boston. Black households could be found throughout the North End, but most were concentrated around Ann Street, near the docks – an area watched by police because of its high numbers of taverns and brothels. Here, Black people worked in low-paying jobs as laborers, as mariners, or by selling second-hand clothes.

Before Black settlers arrived, the North Slope of Beacon Hill, which was part of the historic West End, had a dismal reputation. Visiting British soldiers named part of the hilly area Mt. Whoredom due to its numerous brothels, taverns, and distilleries. In the early 1800s, developers began to build luxury homes for the town’s elite on the south side of Beacon Hill, with a view of the newly built Massachusetts State House. As a result, the 1830s saw marked racial and class-based divisions between the two sides of the Hill along Pinckney Street.

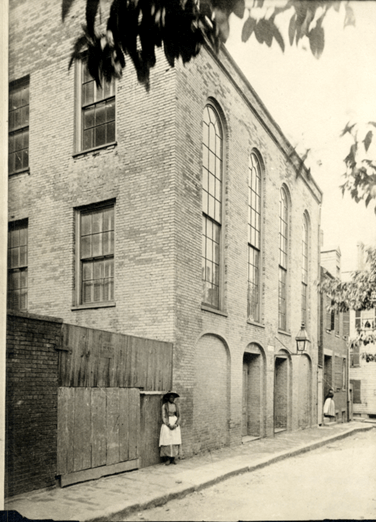

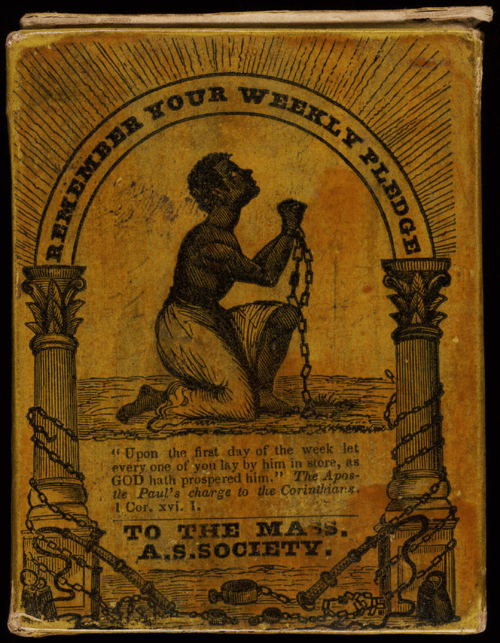

At this time, however, the Black residents of the North Slope neighborhood – running from Pinckney to Cambridge Street, and from Joy Street (formerly Belknap Street) to the Charles River – established the city’s, and arguably the country’s, most powerful Black community. It was here that residents founded the first school solely for Black children; built the oldest standing Black church in the United States; and, in 1832, helped to organize the New England Anti-Slavery Society, with activist and editor William Lloyd Garrison. This community would also go on to participate in future religious, feminist, and temperance campaigns.

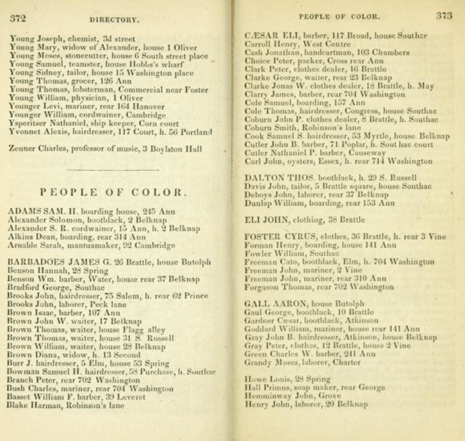

Though most Black Bostonians remained economically marginalized compared to white citizens during the 1830s, there was some modest economic progress for those in certain professions. The 1834 Boston Directory shows that most Black heads of household held low-paying jobs, working as laborers, mariners, boot blacks, or domestics; but, over 40 percent worked as barbers, hairdressers, and owners of boarding houses and other small businesses. Barbers and hairdressers were some of the most successful wage earners in the community, and many owned their own shops. White Bostonians shunned this work as a rule, allowing Black barbers a near monopoly in the industry. In addition, a very small percentage of Black Bostonians were able to break into the professional class, as ministers, educators, and writers. This group was described in Adelaide M. Cromwell’s The Other Brahmins as the elite of the society occupying the North Slope.

Despite these significant economic advances by Black Bostonians, the dawn of the immigration age brought with it a new era of racial segregation in the city. Prior to this, there existed, what some term, an era of “separation,” with informal lines of physical racial division. With the arrival of Germans and Irish in the North End in the early 1830s, Black residents there were pressured to leave. The majority of Black North Enders relocated to the North Slope of the West End, significantly elevating the neighborhood’s share of Boston’s total population. While this consolidation created a numerically stronger black enclave on the North Slope for several decades, the burgeoning forces of segregation persisted and intensified through the latter half of the 19th century and beyond, eventually forcing most Black Bostonians out of the West End.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: The Boston Directory (Boston, Sampson & Murdock company, 1834); D. W Bristol, (2004) From Outposts to Enclaves: A Social History of Black Barbers from 1750 to 1915, Enterprise & Society 5, no. 4 (2004): 594-606; Adelaide M. Cromwell Adelaide, The Other Brahmins: Boston’s Black Upper Class 1750-1950 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994); James Oliver Horton and Lois E Horton, Black Bostonians : Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999); Nathan Kantrowitz, “Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in Boston 1830-1970,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 441 (1979): 41–54; Marla R. Miller, “The Last Mantua Maker: Craft,Tradition and Commercial Change in Boston, 1760-1845,” Early American Studies 4, no. 2 (2006).