Bowdoin Square, Part 1: 18th & 19th Centuries

Bowdoin Square has gone through many phases, including rapid development, growing population, changing fortunes, urban renewal, and attempts at revitalization. Today the name survives mainly in the name of an MBTA station, but examination of Bowdoin Square provides insight into two and a half centuries of Boston history. This article, the first part of two, covers the history of the square in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Bowdoin Square has a complex history. Sometimes overshadowed by more famous neighbors of past and present, including Government Center, Beacon Hill, and Scollay Square, the square merits its own attention as a gateway to the West End and a lens into Boston history during the past 250 years. Today, this busy intersection at the corner of New Chardon, Cambridge, and Bowdoin Streets displays a combination of Federal, modern, and brutalist architecture that can seem a mishmash but that also demonstrates the evolution of the square.

An early map of Boston from 1722 shows a bowling green in the area now occupied by the square. The name “Bowdoin Square” dates from 1788, given to the “space between Cambridge, Green, Chardon, Court and Bulfinch streets,” on the edge of the West End. The square was named after James Bowdoin, a revolutionary, politician, and Massachusetts governor from 1785 to 1787. Until the mid-eighteenth century, the West End was primarily pastureland dotted with some early industrial buildings, like copperworks, distilleries, and a textile mill. In the mid-1700s, the area now known as Bowdoin Square slowly changed from industrial to residential, as affluent families built houses and gardens. Here, Dr. Thomas Bulfinch’s grandson, Charles, was born in his house in 1763, when the neighborhood was still largely pasture with a few wooden stores and houses. Charles Bulfinch became the first professional architect in America and played a huge part in the transformation of Boston after the American Revolution.

Boston’s economy, dependent on maritime trade, suffered greatly during the Revolutionary War. With the end of the war in 1783 and an established and stable federal government in place, the economy slowly rebounded. By the early 1790s, well-to-do merchants were looking for room to build sizable mansions, and they found space in the relatively undeveloped West End. At the same time, Charles Bulfinch was starting architectural and city-planning work, and his early projects focused on the West End and Bowdoin Square. In his position as selectman, Bulfinch supervised the 1793 opening of the West Boston Bridge (where the Longfellow Bridge is today), from the West End to East Cambridge. Previously isolated geographically by the Mill Pond and Beacon Hill, Bowdoin Square was now part of a direct route to Cambridge and Harvard, and rapid development followed. The pastureland of Bowdoin Square filled with expensive brick and stone mansions, two and three stories tall, many designed by Bulfinch in a neoclassical Federal style.

In the Bowdoin Square area, Bulfinch designed several significant residences, including the first Harrison Gray Otis House (1796) on Cambridge Street. Otis was a politician, businessman, and one of the richest men in Boston. The 1796 Otis House is one of Bulfinch’s most famous house designs and survives to this day, albeit with a rocky history. After only five years, the Otis family moved to another Bulfinch house on Beacon Hill, because Cambridge Street was becoming too busy and commercial. The first Otis House on Cambridge Street deteriorated during the nineteenth century and was in shambles when purchased by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (now Historic New England) in 1916. In the 1920s, the house was slated to be demolished when the city widened Cambridge Street to accommodate fast-increasing car traffic. Ultimately, the house was saved by being moved back 42 feet.

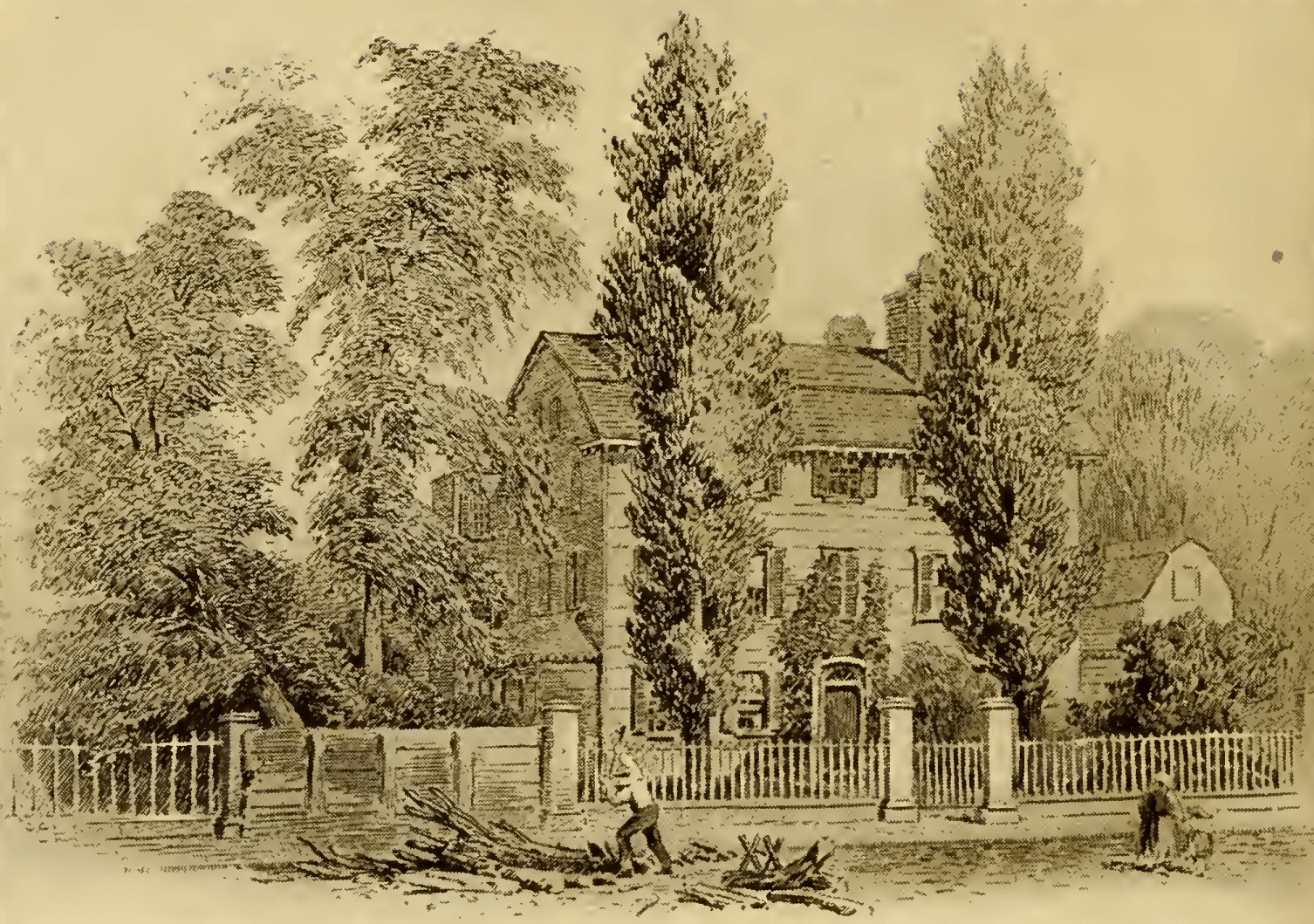

In the early 1800s, Bowdoin Square continued to attract wealthy mercantile and industrial families, and Bulfinch designed showcase homes such as the Kirk Boott house in 1804 and the Blake-Tuckerman houses in 1815. Boott was an industrialist who helped plan the Lowell mills, dams, and canals. The three-story brick Boott house, boasting a roof balustrade and impressive garden, brought ongoing elegance to the square until it was demolished in 1847 (see its connection to the Revere House below). Bulfinch designed the Blake-Tuckerman houses in 1815 for the West End’s largest property owner, Samuel Parkman, who gave the side-by-side residences to his sons-in-law. These handsome granite houses watched over the center of Bowdoin Square until they were torn down in 1902 and replaced by a commercial building.

By the time Charles Bulfinch died in 1844 (in a Bowdoin Square house he had designed), the square was changing in noticeable ways. The West End Bridge had turned Cambridge Street into a noisy and commercial thoroughfare, with increasing numbers of shops, markets, and hotels. Adding to the commotion, Boston’s first horsecar line (horses pulling trolleys on rails), opened on Cambridge Street in 1856, transporting passengers over the bridge to Harvard Square. Fashionable families who had wanted to live in Bowdoin Square in the early 1800s moved to Beacon Hill and then, starting in the 1860s, to the new Back Bay.

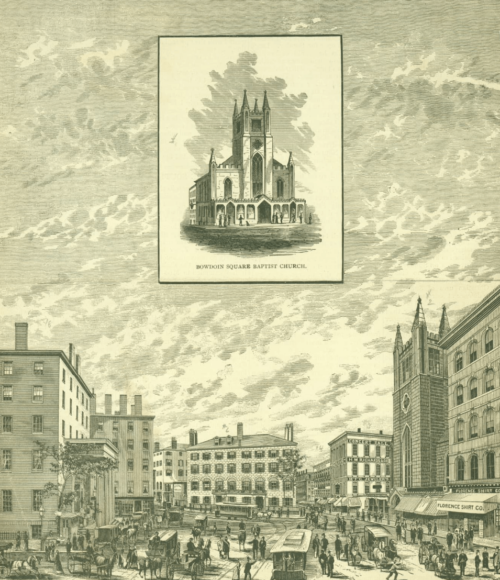

The stories of two buildings show Bowdoin Square’s changing fortunes during the 1800s. In the posh Bowdoin Square area of 1806, the masterful Federalist architect Asher Benjamin built West Church (now called Old West Church) next to the first Otis House on Cambridge Street. One of Benjamin’s finest works, the church’s red brick walls and prominent cupola influenced church design all over New England. Old West was a Congregational parish until 1892, when it closed because of declining attendance. The building was saved and became a branch of the Boston Public Library until 1960. It is now a Methodist church. The paired Old West Church and first Harrison Gray Otis House continue to grace Bowdoin Square, as two of the very few buildings saved during the destruction of the West End in the 1950s and 1960s.

As wealthy families moved out of Bowdoin Square, single-family mansions were no longer needed. Some were sold and turned into boarding houses. In the case of Bulfinch’s Kirk Boott House (1804), it stood in a central location in the square until 1847, when the site was redeveloped into an upscale hotel called the Revere House. Perhaps in honor of Bulfinch, the hotel’s architect, William Washburn, incorporated some of the exterior walls of the Boott House in his design for the hotel. The Revere House immediately became the most prestigious hotel in Boston, the site of glamorous social events and the favorite accommodation for a long list of dignitaries. Guests included Charles Dickens, President Millard Fillmore, the Prince of Wales, and Walt Whitman. In 1850, Senator Daniel Webster chose the porch of the hotel for what proved to be a controversial speech supporting the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Law. The hotel prospered for several years, but by late century both the Hotel and Bowdoin Square were in decline. The hotel burned down in 1912.

Article by Christina Horn, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Historic New England, “Otis House”; Historic New England, “The West End”; Harold Kirker, The Architecture of Charles Bulfinch (Harvard University Press, 1969); National Park Service, “Site of the Revere House Hotel”; Thomas H. O’Connor, The Hub: Boston Past and Present (Northeastern University Press, 2001); A Record of the Streets, Alleys, Places, Etc., in the City of Boston (City of Boston, 1910); Nancy S. Seasholes, ed., The Atlas of Boston History (University of Chicago Press, 2019); Nancy S. Seasholes, Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston (MIT Press, 2003); The West End Museum, “Old West Church”; Walter Muir Whitehill and Lawrence W. Kennedy, Boston: A Topographical History, 3rd Edition (Belknap Press, 2000).