Building the African Meeting House

The African Meeting House, believed to be the oldest standing Black church in America, was incorporated in 1805 and built in 1806. The building, now restored to its 1855 appearance, stands as a testament to the dedication and perseverance of the Black community on the north slope of Beacon Hill (which was at the time part of the West End). The African Baptist Church purchased the land for, fundraised for, and constructed the Meeting House in less than two years. Through this, they created a vital space for the Black community’s religious, political, and social gatherings.

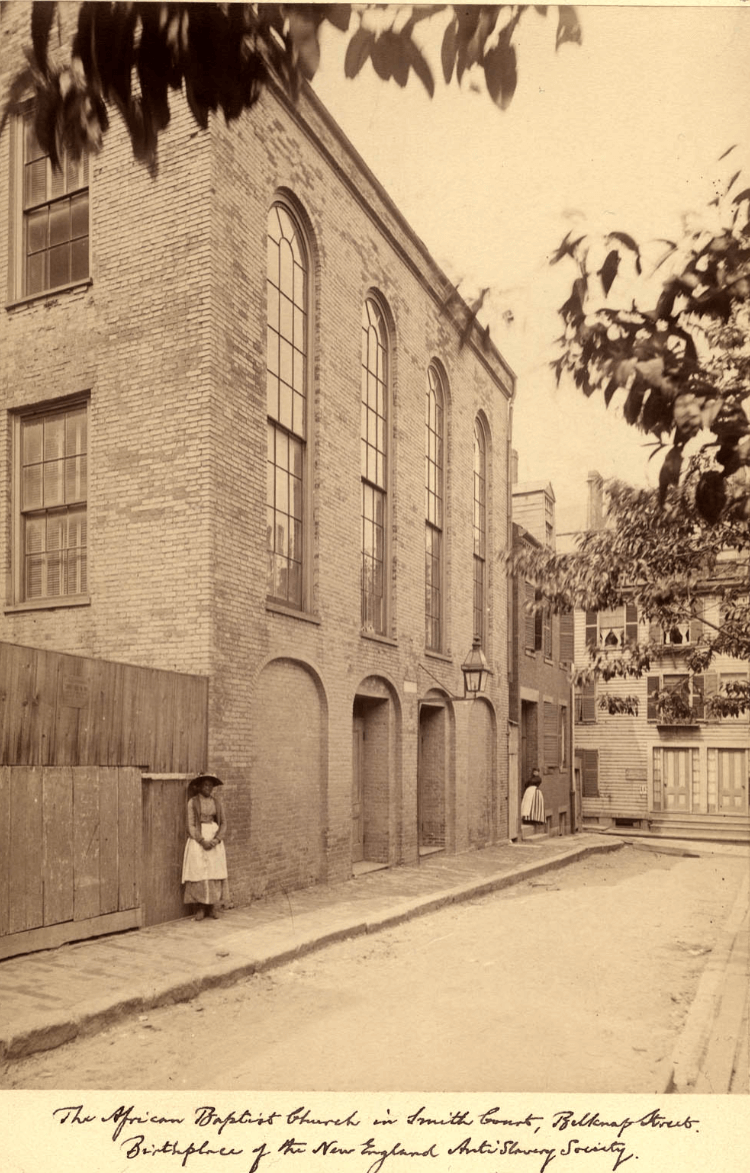

Completed in 1806 in the historic West End, the African Meeting House is considered the oldest standing Black church building in the United States. For almost a century, the edifice acted as an influential and versatile hub for the Black community: It was the first African Baptist Church north of the Mason Dixon Line; the first place of worship built for Black people in Boston; and a critical site for religious, political, social, and educational gatherings.

The African Baptist Church was officially incorporated on August 8th, 1805, with twenty-four members, fifteen women and nine men. By this time, there was already a growing community of African Americans who had begun to settle on the north slope of Beacon Hill. The land for the church was purchased a few months prior, on March 23rd, by three members of the church committee from Augustine Raillion. The plot, which cost $1,550, was 49 by 59 feet.

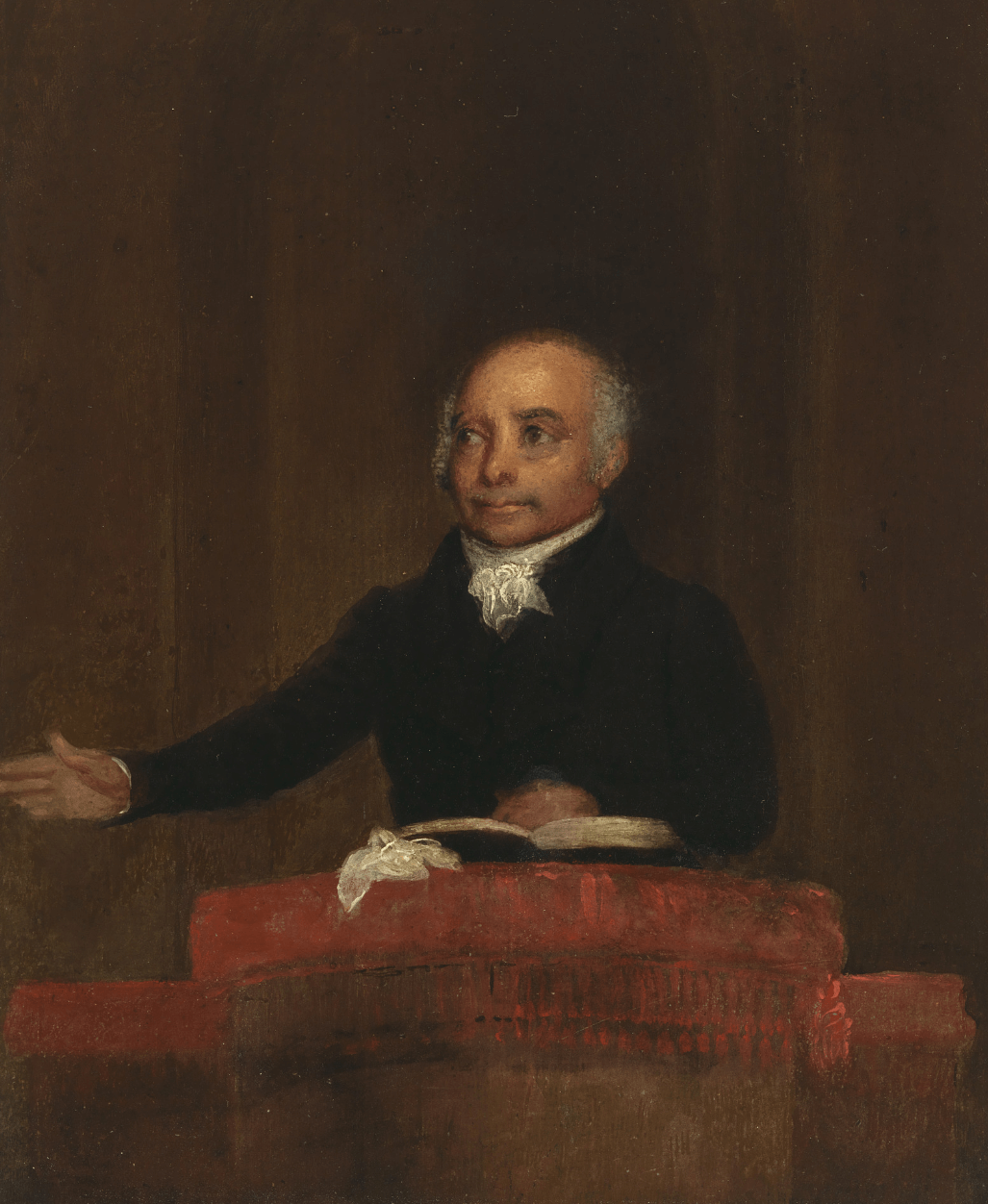

In July 1805, the congregation appointed Thomas Paul, Scipio Dalton, and Cato Gardner to raise funds to build the church. Thomas Paul was born in New Hampshire, the son of a freed slave named Caesar Nero Paul, and would become the church’s first pastor. Originally, Paul had attended the First Baptist Church, then in the North End. However, after being blocked from having an equal role in church activities and being forced to sit in segregated pews further away from the minister, Paul decided to help found the African Baptist Church. Both Scipio Dalton and Cato Gardner were former slaves. Gardner, who was a blacksmith by trade, led the fundraising effort by raising $1,500. Further money was raised from reselling salvaged materials; from selling an excess building on the purchased lot; from donations from individuals in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Maine; and from selling pews in advance to members of the African American community.

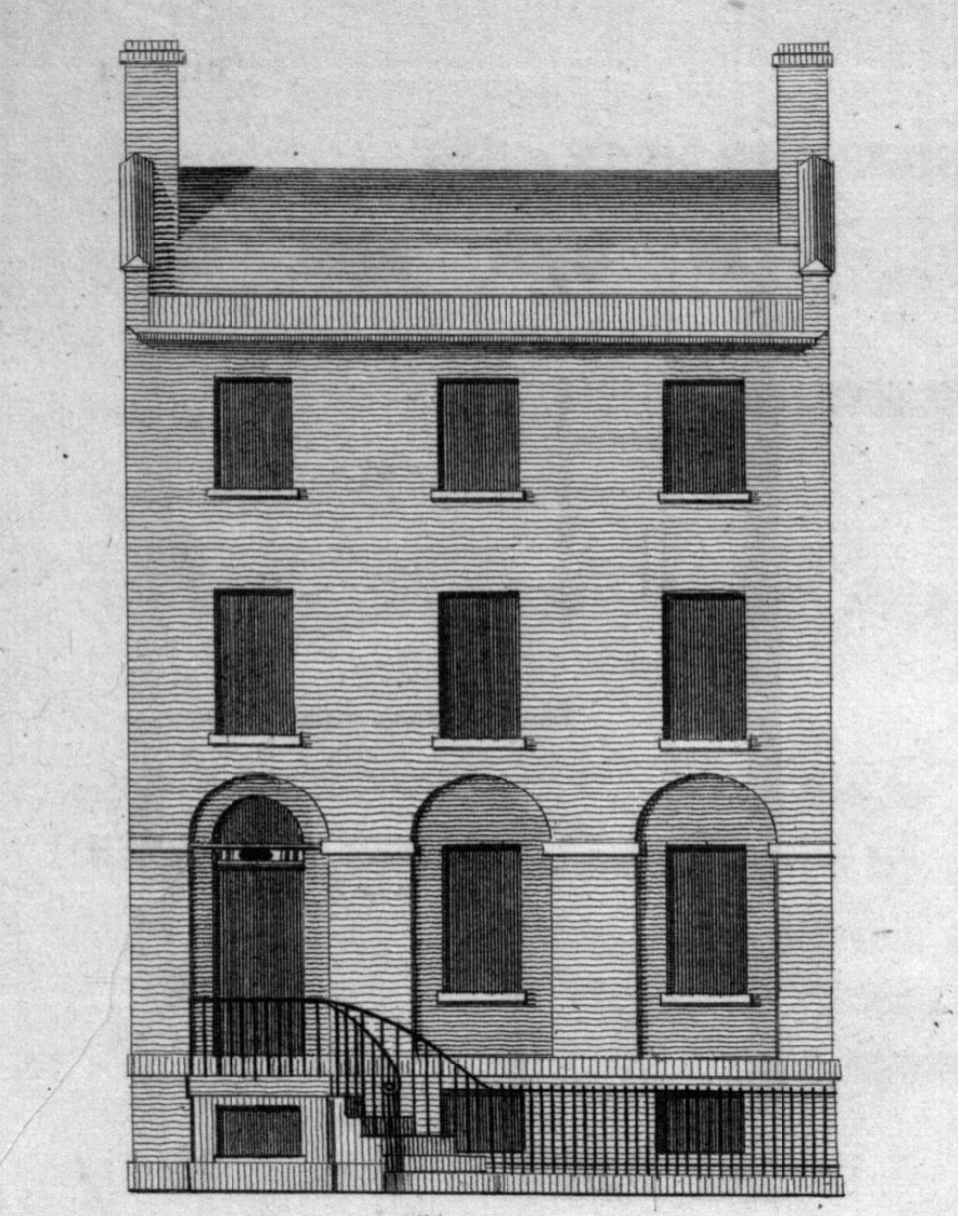

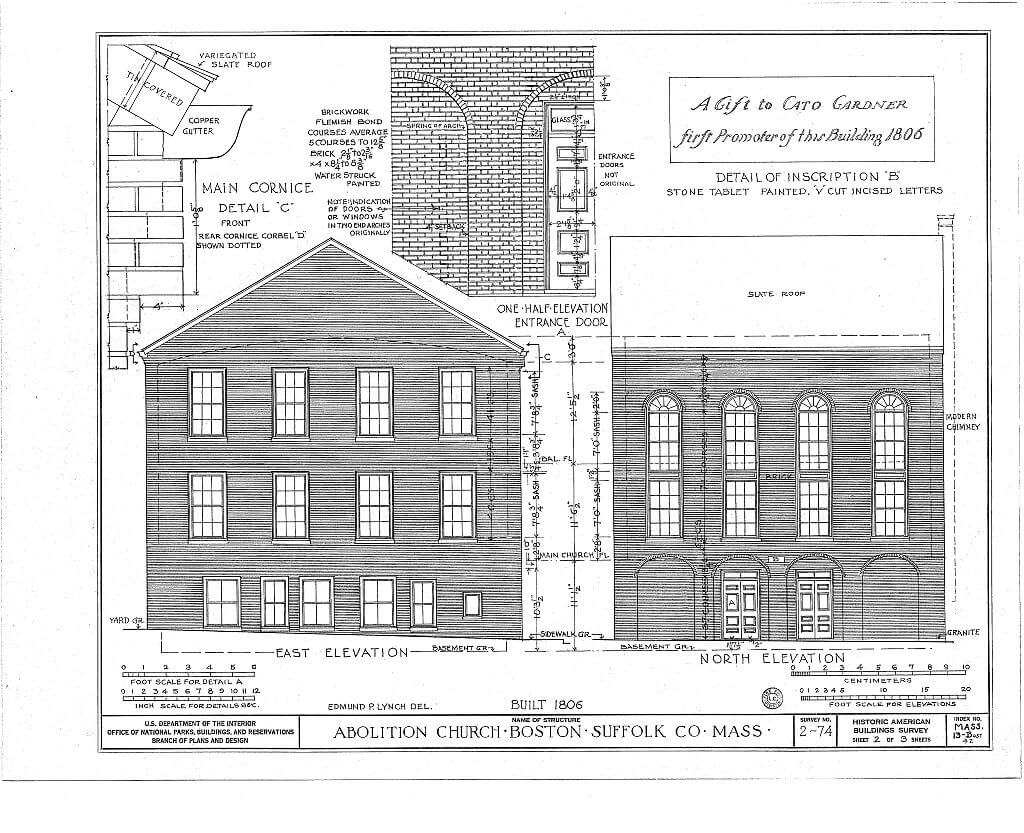

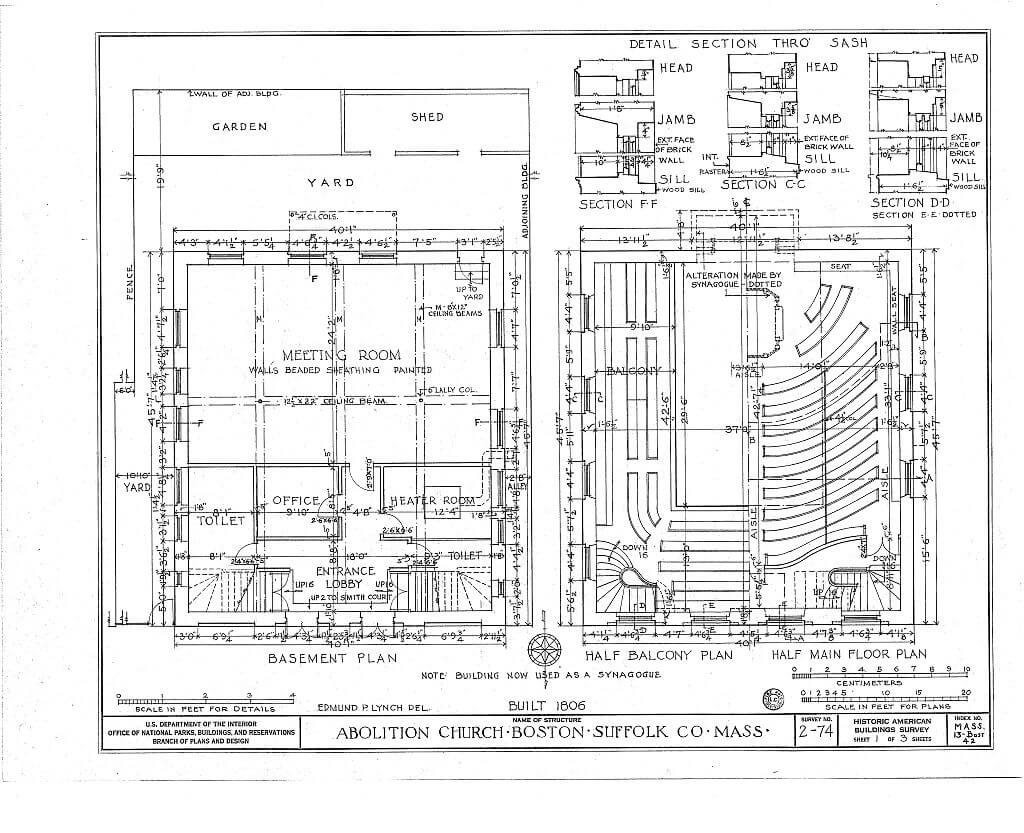

After raising $2,500, a second committee was formed to oversee the building of the church, which consisted of six white men: Daniel Wild, an auctioneer; John Wait, a chocolate maker; William Bentley, a baker; Mitchell Lincoln, a merchant; Ward Jackson, a housewright; and Edward Stevens, a baker. Although no original architectural drawings from the Meeting House have been found, the building’s design was likely created or inspired by architect Asher Benjamin. The original design of the Meeting House shares a number of commonalities with a plate from Asher Benjamin’s The American Builder’s Companion (1806), showing a “Plan and Elevation for a Small Townhouse.” These parallels have led many to speculate that Benjamin or Ward Jackson, the only housewright on the building committee, may have been responsible for the design. Jackson and Benjamin were undoubtedly acquainted, as they were both members of the Society of Associated Housewrights. Jackson was also likely aware of Benjamin’s drawing from The American Builder’s Companion, as the guide had already been submitted to the Society for review prior to its publication.

While the design origins of the Meeting House remain nebulous, it is clear that the church was constructed by both white and black laborers and craftsmen. An 1808 account of labor costs indicates that $1,512.77 was spent on carpenter work and $656.47 on mason work. Of the latter amount, Abel Barbadoes, a black man known as a “master mason,” received the largest sum. Materials were purchased, then carted to the building site for $20.96, using a horse that was bought or borrowed for $30. Some of the larger purchases include: “sundrys” ($5,012.30); sandstone ($308.30); slating ($320); lumber ($195.13); and salvaged items from the Old West Church, which was currently being rebuilt, including timber, windows, and a pulpit ($472.50). Though $4,772.54 was raised for the Meeting House’s construction, costs far exceeded this initial amount, and the money owed to the building committee was not paid off until 1819. Nevertheless, in December 1806, the African Meeting House was officially opened and dedicated as the “First African Baptist Church.”

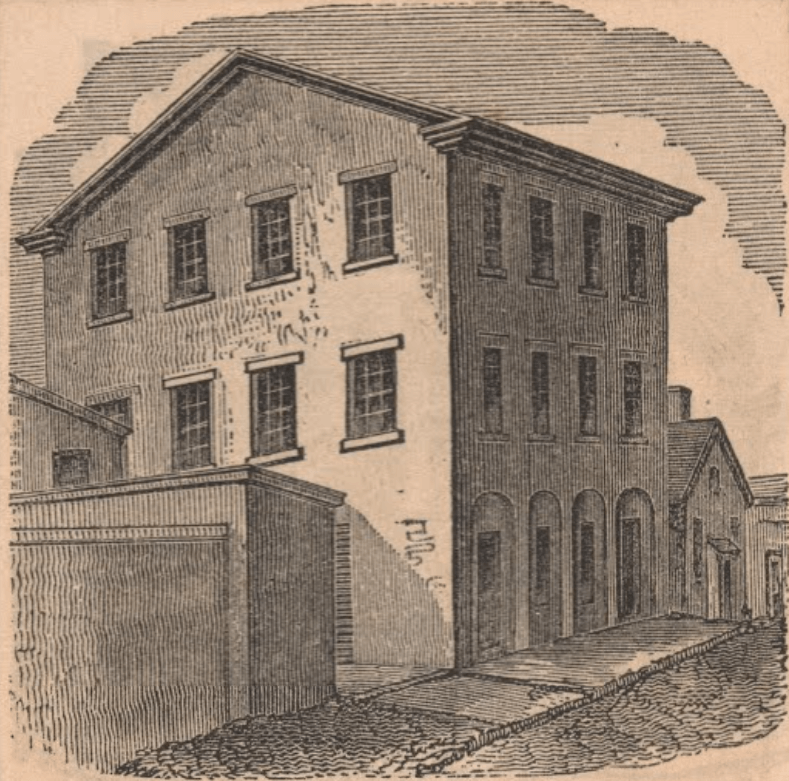

Relatively little documentation on the African Meeting House’s original exterior appearance exists. From early written accounts and an 1843 engraving (pictured above), it can be inferred that the Meeting House was a three-story, square, brick building, with bays, a gable roof, projecting cornices, blind arches, and five exterior doorways. The first story of the African Meeting House contained a schoolroom, for public-school and Sunday-school classes, and the “minister’s room,” which was often rented out to private members of the Black community. The second story was the sanctuary, and the third story its gallery. In addition to holding religious services, the Meeting House became a central gathering place for the Black community: abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and Maria Stewart spoke here; the Massachusetts General Colored Association met here; and the New England Anti-Slavery Society was founded here.

Over the course of two centuries, the Meeting House building was adapted to fit the needs of its community. Its first major renovation was completed in 1855: doors were both bricked up and added, windows were enlarged with half-round heads, the cornice was altered, the rake of the gallery was changed, and the apse was added. In 1898, the Baptist congregation sold the African Meeting House and moved their church to the South End. The Meeting House became the Jewish Congregation Anshi Libavitz in 1904, which it remained until the Museum of African American History purchased the meeting house in 1972. After undergoing a multi-year renovation, in which the building was restored to look like it did in 1855, the Museum reopened to the public in 2011. The 1855 appearance was chosen because its design was better documented than the original 1806 exterior.

Through its over two-hundred-year history, the building went from the first Black church in Boston, to a synagogue, to a museum, and its appearance shifted accordingly through waves of renovation and then back to its 1855 form. Ultimately, the story of building the African Meeting House is a tale of the dialogic relationship between building both a physical space and a series of communities.

Article by Grace Clipson, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: “Investigating the Heart of a Community: Archaeological Excavations at the African Meeting House, Boston, Massachusetts,” Andrew Fiske Memorial Center for Archaeological Research Cultural Resource Management Study 22 (2007); Kathryn Grover and Janine V. da Silva, “Historic Resource Study Boston African American National Historic Site,” 2002; David B. Landon and Teresa D. Bulger, “Constructing Community: Experiences of Identity, Economic Opportunity, and Institution Building at Boston’s African Meeting House,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 17, no. 1 (2013); National Park Service; WBUR; Barbara A. Yocum, “The African Meeting House: Historic Structure Report,” Building Conservation Branch, US Department of the Interior (1994).