Charles Sumner

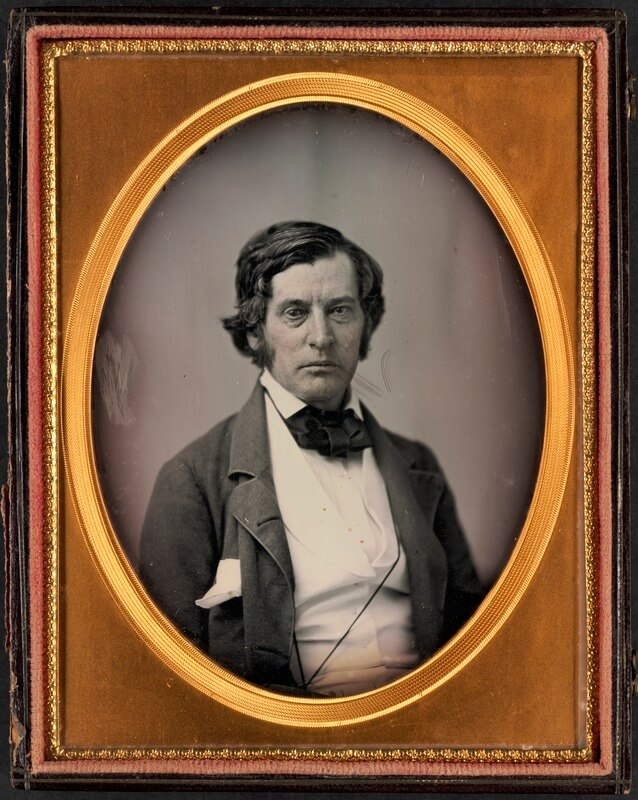

Charles Sumner (1811-1874) was a lawyer and United States Senator who was a vocal abolitionist and civil rights advocate. He was born and lived most of his life on the North Slope of Beacon Hill, where he had close connections with the Black and abolitionist community.

Charles Sumner, and his twin sister Matilda, were born on Irving Street on the North Slope of Beacon Hill in 1811 to Charles Pinckney and Relief Jacob Sumner. Sumner was exposed early to civil rights issues by his father, a Harvard-trained lawyer and abolitionist who publicly called for legalizing interracial marriage and integrating Boston’s public schools. During Sumner’s childhood, the North Slope neighborhood had the largest population of Black people in Boston, and many of the city’s most powerful leaders of the Black community lived near the Sumners, including the Vassall family and Reverend Thomas Paul.

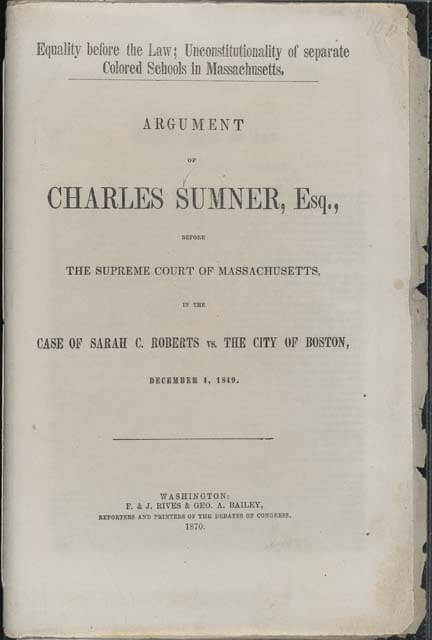

Sumner followed the educational path of his father, attending Harvard College and Harvard Law School in the 1830s. He practiced law and toured Europe in the 1840s. Upon returning to Boston, he used his law background and took up the cause of abolition. He teamed up with his neighbors, many of whom were heavily involved in the abolitionist movement. James and Maria Stewart lived near the Sumner home (20 Hancock St), and Southern born writer David Walker rented a room next to the Stewarts. In 1849, he worked with neighbors William Cooper Nell and attorney Robert Morris to sue for the desegregation of Boston public schools (Roberts v. City of Boston), but they ultimately lost the case.

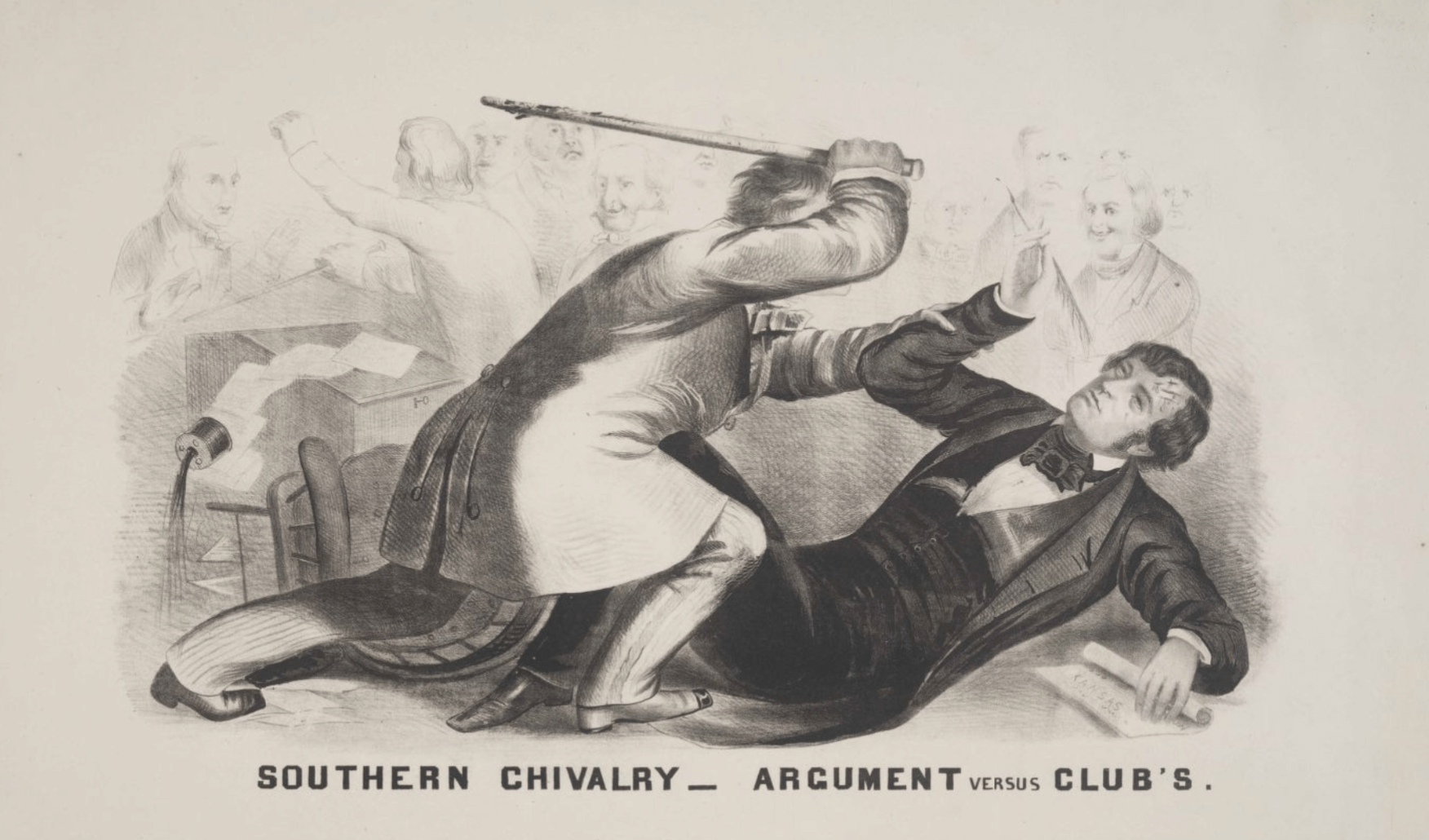

Sumner also began to explore politics as a means of making meaningful change. He was instrumental in forming the Free Soil Party, which fought against the policies of slave-holding President Zachary Taylor, and supported keeping the newly-forming western states, such as Kansas, slave free. In 1851, Sumner ran for and was elected to the U.S. Senate as a Republican, where he immediately acquired a reputation as a passionate opponent of slavery. He continued to fight against Western slavery, and feuded with South Carolina senator Andrew P. Butler, who co-authored the pro-slavery Kansas-Nebraska Act. This led one of Butler’s colleagues, U.S Representative Preston Brooks, to attack Sumner with a cane in 1856 in the Senate Chamber. The injuries were substantial enough to keep Sumner out of Congress for the rest of his first term while he recovered.

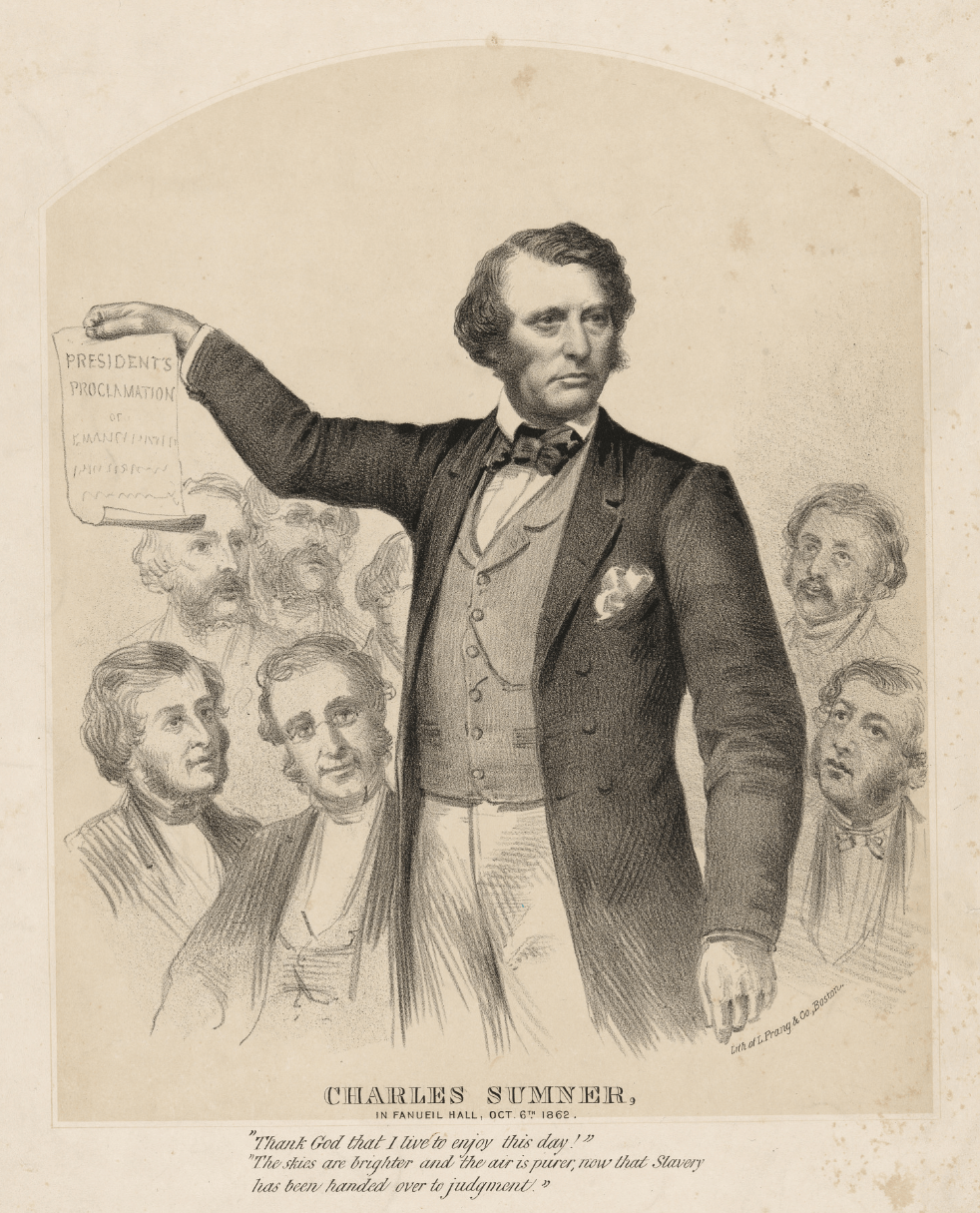

Sumner was reelected for a second term. During the Civil War, he continually fought to allow Black men to enlist in the Union Army and for emancipation to be included in his party’s platform. With the end of the war and emancipation, Sumner tirelessly called for the complete freedom and equal rights of Black people. He introduced the Civil Rights Act of 1870, which allowed for equal access for Black people on “railroads and steamships, accommodations, theaters, public schools, churches, cemeteries, and jury service,” but it was voted down. He continued to introduce the act in Congress every year until his death of a sudden heart attack in 1874.

In 1875, Congress passed a weaker version of Sumner’s civil rights act, which excluded many of his demands, such as school desegregation, but eventually the U.S. The Supreme Court repealed the law completely. Finally in 1964, 90 years after his death, Sumner’s dream was realized with the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Charles Sumner: American Battlefields Trust; Library of Congress; National Portrait Gallery; John Stauffer, “Charles Sumner’s Political Culture and the Foundation of Civil Rights; Or, The Education of Charles Sumner,” The New England Quarterly (2023) 96 (4): 322–340; US Senate: Charles Sumner: Featured Biography.