Chloe Russell

Chloe Russell, a Black woman who owned property on Belknap Street in the West End during the nineteenth century, was the attributed author of The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book in an era when fortune telling and dream interpretation was popular and entertaining.

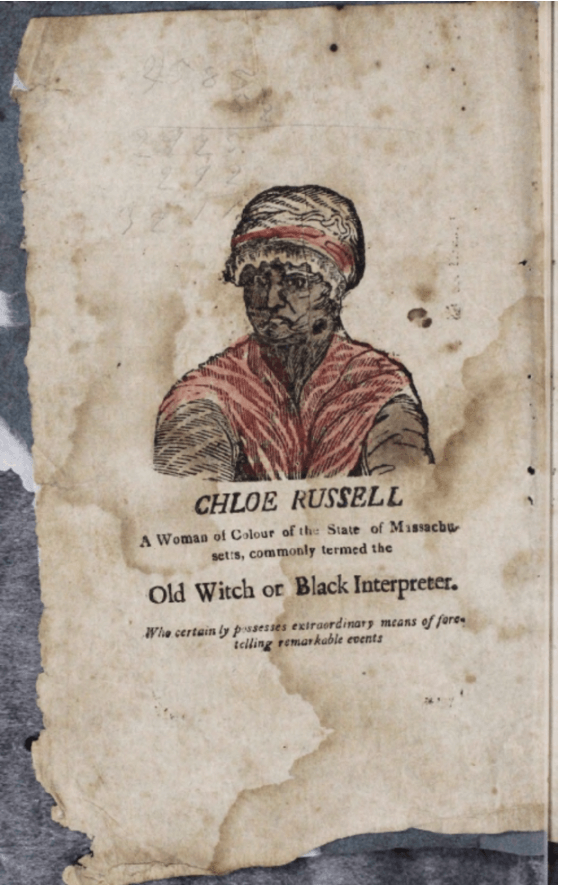

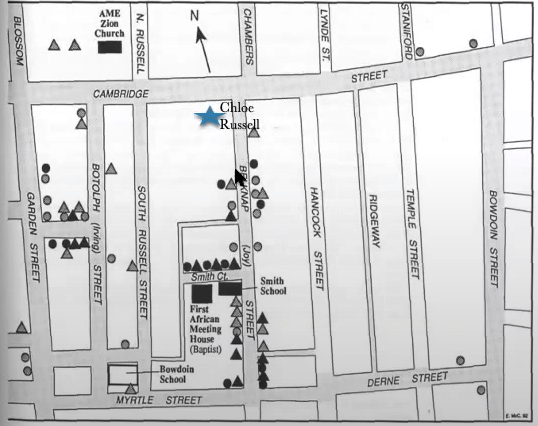

Chloe Russell (also spelled Russel) lived on Belknap Street (now Joy Street) in the historic West End during the 1820s and 1830s, according to the federal census and Boston directories from the period. The federal census referred to Russell as a “free colored female,” and the city directories indicated that Russel worked as a washerwoman (1821-1825), then a cook (1829-1833). Russell was one of six Black women who owned property in the neighborhood during the nineteenth century, according to Adelaide Cromwell’s seminal study of the Black West End. Because the 1820 and 1830 census indicated that multiple people lived at Russell’s address, from a “free colored male under 14” to a “free colored female 14 to 26,” Chloe Russell, listed as a widow, may have provided lodging to extended family or owned a boarding house. Russell was also attributed as the author of The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book, by Chloe Russell, a Woman of Colour of the State of Massachusetts. Versions of the book were published in Exeter, NH by Abel Brown in 1824, and also in Boston by Tom Hazard around 1800 (possibly 1815 or 1825). There is some uncertainty about whether Chloe Russell truly wrote The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book, or whether her name and likeness was attached to the book by white publishers to capitalize upon a prevailing stereotype of the “Black Interpreter” with occult knowledge. But regardless of this uncertainty, there was a real Chloe Russell living in the West End during the nineteenth century, and The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book is a compelling historical artifact in its own right.

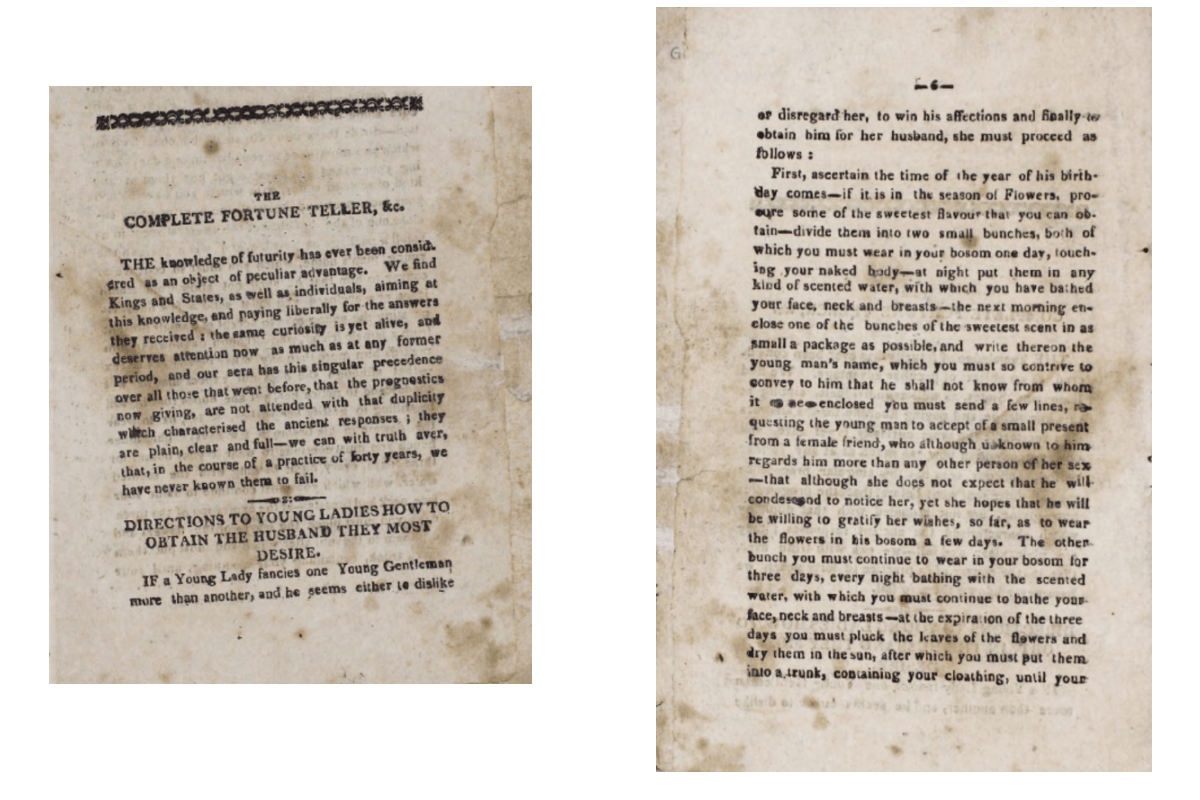

Nicole Aljoe, professor of English at Northeastern University, and her undergraduate students have reproduced a digital edition of Russell’s book for the Early Black Boston Digital Almanac, a website which uses digital exhibits and archival material to engage audiences about Boston’s early Black history. The edition of The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book discussed and pictured below was published by Tom Hazard and presently held by the Boston Athenaeum. The Boston edition of The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book began with an introduction that attested to the demand for fortune tellers and to the accuracy of Russell’s predictions over forty years. Different versions of the book include guidance on the symbolism of dreams, astrology and palmistry (reading palm lines), inferring someone’s future from the placement of moles on their body, and rituals for finding a spouse or knowing whether a distant friend is alive and well.

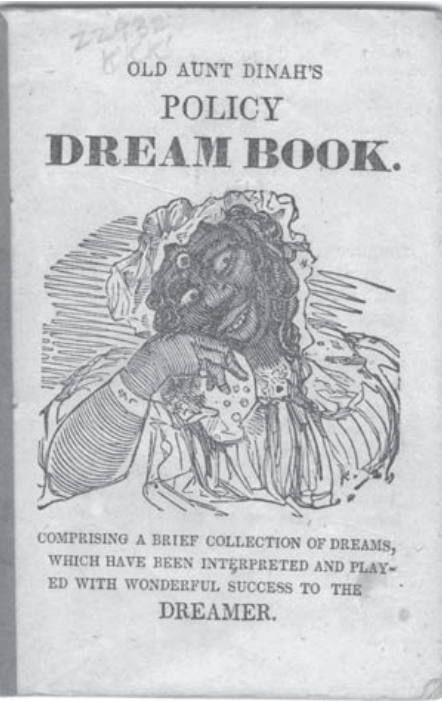

Eric Gardner, professor of English at Saginaw Valley State University, raised an important question in a seminal essay on Russell’s book: whether Chloe Russell was the true author of the Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book. White publishers may have attached Russell’s name to the text to capitalize on popular stereotypes about mystics and spiritual guides of African descent (also called “cunning people” in the nineteenth century). One example of this kind of marketing would be Old Aunt Dinah’s Policy Dream Book, published in New York circa 1850; this book very clearly uses an invented, minstrel-like figure to advertise a dream book similar to Russell’s. However, because Chloe Russell was a real woman of color in Boston, and the name does not carry the same racist overtones as “Old Aunt Dinah,” it is unlikely that “Chloe Russell” was an invention by a publisher such as Tom Hazard.

Although Chloe Russell is the likely author of her Dream Book, embellishments in her autobiography (included only in the c. 1815 edition of the book) suggested, for Gardner, that her backstory, and potentially her authorship, could have been fictional. In the autobiography, Russell originated from Sierra Leone, was kidnapped by white enslavers and sold to planter George Russell in Virginia, and secured her freedom after using occult knowledge to help another planter find buried money, some of which he used to buy Russell’s independence. Gardner raised questions about two significant details of the Russell autobiography. First, she was apparently born “three hundred miles southwest of Sierra Leone,” when that distance would have gone out into the Atlantic Ocean. And second, Russell would have attracted lots of public attention had it been true that she allegedly earned $3,000 as a “seer” in Virginia, over the course of ten years since achieving her freedom, and used “almost every cent” to buy the freedom of other Black people enslaved by George Russell. Another significant question, unaddressed by the autobiography, would be when Russell left Virginia for Boston. But nonetheless, “Chloe Russell” was unlikely a pseudonym or an invented character, because there was in fact a real “woman of colour in the state of Massachusetts” with her name.

Not all dream interpretation was alike, even as manuals for reading dreams often copied previous books. The Library Company of Philadelphia, which owns an early edition of the Dream Book, calls Russell’s book “Artemidorus revisited, one of many cheap editions of this ancient and standard guide to the meaning of dreams” referring to ancient Greek diviner Artemidorus’s The Interpretation of Dreams (200 AD). But Russell’s guidance on dreams was not an imitation of published work going so far back in time, and sometimes contradicted, not copied, older works. On the shared subject of dreams about children, Artemidorus wrote that “to dream that one has or sees young children, especially new-born infants, when they belong to the dreamer, is bad for both men and women. For it signifies cares, griefs, and anxieties over some important matters, since it is impossible to raise children without them.” Russell, on the other hand, wrote that “to see children in your dream, promises riches and happiness in this life.” These conflicting interpretations bear less on any objective truth about dreams or childrearing and more on how the interpreter believes their readers should think about children once they appear in a dream.

Chloe Russell was one of six Black women who owned property in the West End during the nineteenth century, a significant achievement by itself. But as we can fairly assume that she wrote the Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book, which reveals a unique connection between the Black West End and the popular nineteenth-century genre of fortune telling books.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Early Black Boston Digital Almanac; Library Company of Philadelphia; Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America; Eric Gardner, “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour’” (JSTOR); Cromwell – The West End Museum