Christiana Carteaux Bannister and Edward Mitchell Bannister

Entrepreneur Christiana Carteaux Bannister and artist Edward Mitchell Bannister married in Boston’s West End in 1857. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, they were active in Boston’s abolitionist and artistic communities. During these years and beyond, their symbiotic financial and creative partnership helped to bolster both of their careers and their community connections.

Christiana Carteaux Bannister – a successful entrepreneur and hairdresser – and Edward Mitchell Bannister – one of the first Black painters to achieve national recognition in the arts – were active members of Boston’s cultural, artistic, and abolitionist circles in the 1850s and 1860s.

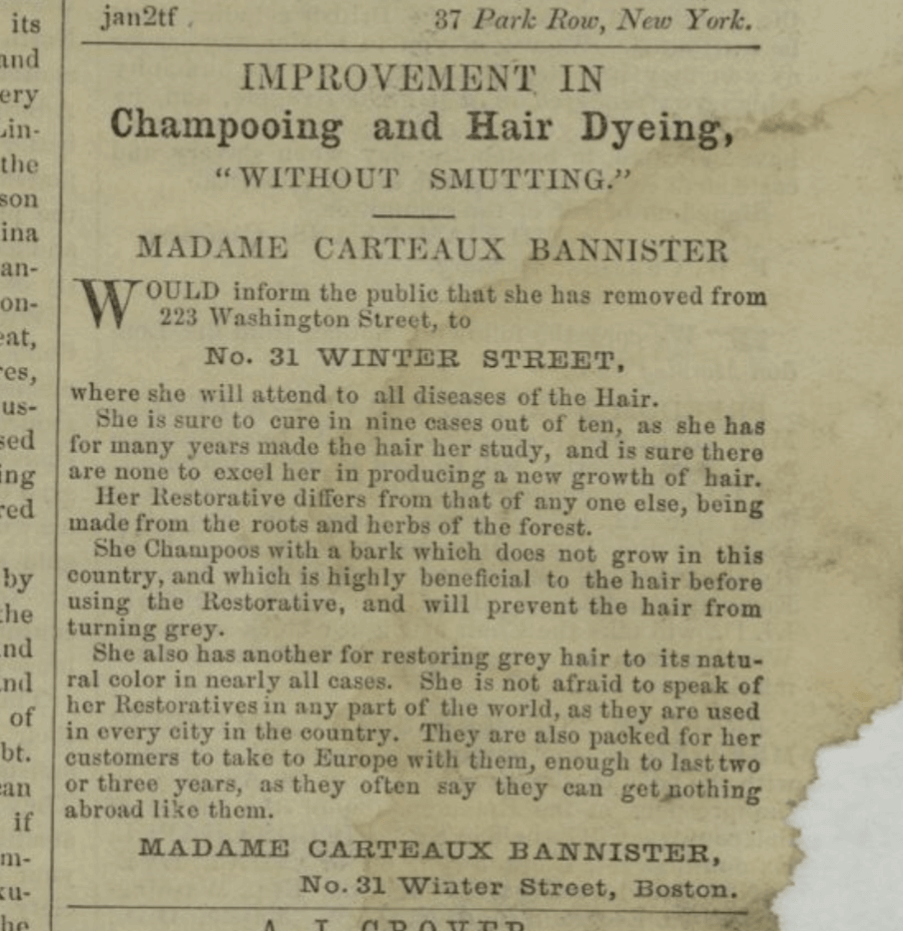

The former was born Christiana Babcock in North Kingston, Rhode Island in 1819. She was of Narragansett and African American parentage, the descendant of slaves from southern Rhode Island’s plantations. She first appears in the Boston Directory in 1846, at which point she described herself as a milliner (a maker of women’s hats). She was married to Desiline Carteaux, a cigar maker, and living on Cambridge Street. The marriage quickly fell apart, and by 1850 she was residing with friends. In 1853, she returned to the Boston Directory as a hairdresser with her own salon.

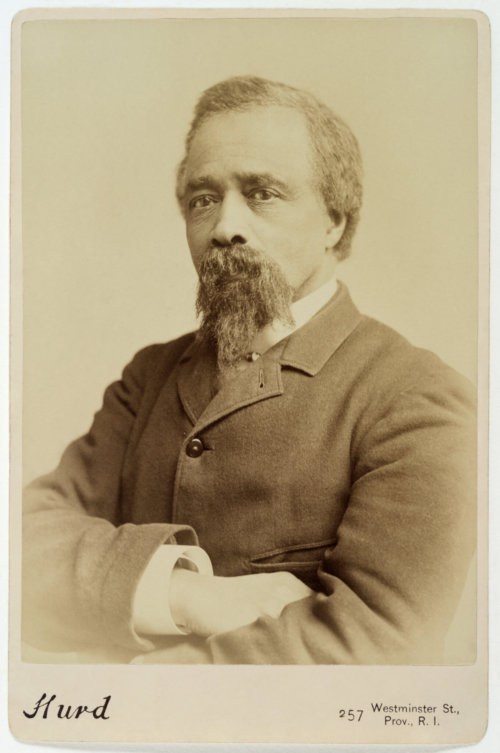

Edward Mitchell Bannister was born in November 1828 in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada. His father was from Barbados, West Indies, and the background of his mother is unknown. In 1848, Bannister moved to Boston. While he wanted to be an artist, he was denied formal academic training due to his race. Bannister took on a variety of menial jobs to support himself, and studied art independently in his spare time.

In 1853, Madame Christiana Carteaux hired the young Bannister to work as a barber in her salon. By this time, Christiana was a successful businesswoman – between 1850 and 1857, she worked at and owned various salons on 284 Washington Street, 191 Washington Street, 365 Washington Street, 323 Washington Street, and 20 West Street. Bannister moved in with Christiana, and by the mid-1850s, had become known in the Black community as a skilled portraitist. The artist received his first commission in 1854 from Dr. John van Salee de Grasse, a prominent Black physician. The painting, whose whereabouts are now unknown, was a seascape titled, The Ship Outward Bound.

On June 10, 1857, Christiana and Edward married at the Temple Street Episcopal Church. Edward then left his job as a barber, and Christiana supported him financially as he studied art and tried to further launch his nascent painting career. By 1858, Edward was able to list himself as a professional artist in the Boston Directory, living and working at 170 Cambridge Street.

Throughout the 1860s, Madame Carteaux Bannister continued her salon business, located at 31 Winter Street and later 43 Winter Street, which she frequently promoted in William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. Her advertisements referred to her as the “Hair Doctress” who “stands second to none in Hair-Dressing and Champooing.”

While Edward continued to face barriers in acquiring access to formal study and patronage, his connection to a small but active circle of Black artists helped to mitigate some of these obstacles. He befriended the Black portraitist William H. Simpson, and had a studio room two doors away from Edmonia Lewis; he often exhibited at abolitionist fairs and moved within the same patronage circles as them and other Black artists. As mentioned, Bannister received his first commission from Black physician and abolitionist Dr. de Grasse, and it was abolitionist William Cooper Nell who penned the first published praise of Bannister as a promising young artist in his 1855 The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution.

By the mid-1860s, Bannister’s access to the White art world began to grow. He spent a year studying photography in New York around 1862; was able to enroll in the evening drawing classes of sculptor-anatomist Dr. William Rimmer; and, by October 1864, secured a room for himself at the Studio Building at 110 Tremont Street, where well-known artists like John La Farge and William Morris Hunt also had rooms. It is likely that Bannister saw the Barbizon School-style paintings of William Morris Hunt here and at other public exhibitions throughout the city. He also almost certainly saw the 1866 and 1867 Allston Club exhibitions of works by Jean-François Millet, Gustave Courbet, and Camille Corot, which were held in the Studio Building’s first floor. In his mature career, Bannister would become known for his own pastoral scenes in the French-Barbizon-School vein.

During this period, the Bannisters were also active members of Boston’s Black activist and abolitionist community. From 1859 through 1860, the couple boarded at Lewis and Harriet Hayden’s house at 66 Southac (now Phillips) Street, which was an important stop on Boston’s Underground Railroad and a gathering point for abolitionist leaders. Christiana and Edward stayed close to the Haydens after their stay, moving just a block away to 28 Grove Street. Both of the Bannisters took on an active and public role in anti-slavery activities and associations. In January 1863, Massachusetts Governor John Andrew began recruiting for the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first Black regiments to serve the Union Army in the Civil War. Christiana, then president of the Colored Ladies Relief Committee, presented the regiment with its colors in Readville, Massachusetts, and also supported the regiment by fighting for equal pay for its Black members. Further, Christiana used her salons as a meeting place for abolitionists and organized fairs to raise funds for widows of the Black soldiers killed in battle. Edward was an active member and a recording secretary for the Colored Citizens of Boston, and his name frequently appears on abolitionist petitions and in The Liberator. Many of the abolitionist figures he worked with appear in Edward’s art of the period. For example, Edward painted and donated a portrait of Robert Gould Shaw, the commander of the 54th Regiment who was killed in action, to raise money for the abolitionist cause.

In 1869, the Bannisters moved to Providence, Rhode Island – this was probably due to both Madame Carteaux’s thriving salon establishment in Providence, as well as the growing racial tensions in Boston in the late 1860s. A few years after settling in Providence, Edward was awarded the first-prize medal at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition for his painting, Under the Oaks (current location unknown). Upon learning he was Black, the Exposition jury sought to rescind the award but, after protest from other artists, Bannister received the prize. After the Centennial Exposition, Edward’s status as an artist, and his number of commissions, grew. He focused the remainder of his career on painting New England landscapes with loose, impressionistic brushwork and light colors. Christiana continued to run her hair salon and, in 1890, founded the Home for Aged Colored Women on East Transit Street in Providence. Her hair salons closed sometime after the 1890s. In 1901, Edward Bannister died and Christiana’s health began failing, as well. She moved into the Home for Aged Colored Women and was later transferred to the State Hospital for the Insane, where she died.

The Bannisters’ time in Boston, and after, is a story of partnership – not only a marriage, but a mutually-supportive financial, emotional, and creative partnership. Indeed, while Christiana was, and still is, often overlooked, it was her initial success as a hairdresser that enabled Edward to become a full-time artist. Later in life, Edward reflected on his relationship with his wife, saying: “I would have made out very poorly had it not been for her… my greatest successes have come through her, either through her criticisms of my pictures, or the advice she would give me in the matter of placing them in public.”

Article by Grace Clipson, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: Adelaide Cromwell, “The Black Presence in the West End of Boston, 1800-1864: A Demographic Map,” in Courage and Conscience: Black and White Abolitionists in Boston, edited by Donald Jacobs, 155-168 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993); Juanita Marie Holland, Edward Mitchell Bannister, Kenkeleba House & Whitney Museum of American Art (1992); Jane Lancaster, “‘I Would Have Made Out Very Poorly Had It Not Been for Her’: The Life and Work of Christiana Bannister, Hair Doctress and Philanthropist,” Rhode Island History Journal 59 (2001): 103–122; Jessie Smith, Encyclopedia of African American Business (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017).