Domingo Williams

Domingo Williams was an attendant and caterer who lived with his family in an apartment in the African Meeting House from 1819 to 1830. A 2005 archaeological dig behind the African Meeting House, in conjunction with mentions of Williams in local and national newspapers, help to illuminate Williams’ prosperous catering career, his activist involvement in Boston’s Black community, and his time living in one of the city’s most important Black social-religious centers.

In 1806, the African Meeting House was built on the north slope of Beacon Hill, in the historic West End, and served as an African Baptist church, a meeting place for events, and a cultural center for the Black community. It is now considered the oldest standing Black church building in the United States. The basement of the building contained two apartments. From 1819 to 1830, businessman Domingo Williams and his family lived in one of the apartments. It is believed that artifacts recovered from a 2005 archaeological dig at the African Meeting House backlot illustrate his success and prominence in the community.

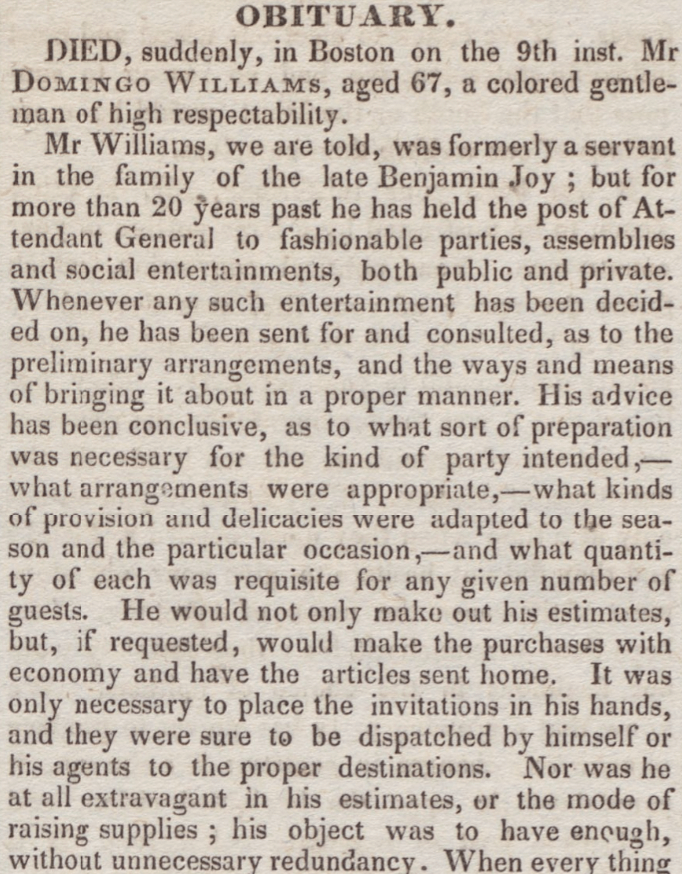

The ground floor of the African Meeting House was used for dinners, meetings, Bible study classes, and celebrations. As a caterer, Domingo Williams provided many of the meals in the space. He also served the wider community. City directories listed his occupation as “waiter” and his 1832 obituary in The Liberator stated that he was “Attendant General to fashionable parties, assemblies and social entertainments, both public and private” for over 20 years.

In an 1830 survey of Boston’s Black workers, “waiter” was one of eight job categories that accounted for almost all of the 175 men and women listed. Most free Black men in antebellum Boston were employed as laborers, mariners, barbers, bootblacks, clothing dealers, or waiters. In waitering, there was an opportunity to advance in status and pay; a promotion to head waiter often came with a higher degree of social status in the community. Some waiters evolved into caterers, providing meals and scheduling programming for public banquets. Caterers typically hired their independent services for events; performed the work at the host’s location; and at times provided plates, flatware, and glassware. While he lived in and worked out of the African Meeting House, Domingo became the caterer and organizer of events there and in the broader Boston community, providing food, entertainment, decorations, linens, and dishes.

Little is known about Domingo Williams’ early life and how he came to be a successful entrepreneur. His obituary states that he had been a servant for the family of Benjamin Joy, the first U.S. Consul in India and prominent member of the Mount Vernon Proprietors. By his early fifties, Domingo had gone from being a servant in the Joy home, to a waiter, to an enterprising caterer and influential community member living in Boston’s center of Black cultural and spiritual life.

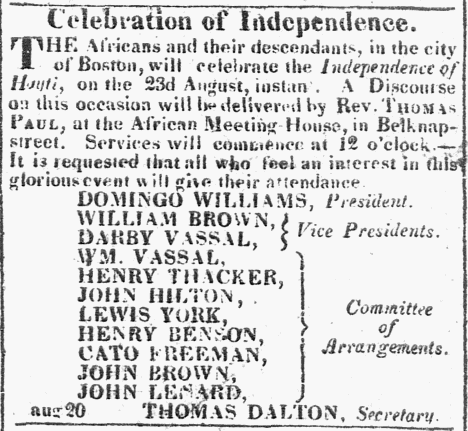

Articles from local and national newspapers help to paint a rough sketch of Williams’ life and his impactful contributions to his community. The Boston-based Columbian Centinel reported that, when the King of France formally recognized Haiti’s independence in 1825, Domingo served as the President of Boston’s celebratory festivities (image below). On August 23 of that year, Williams and other Black community members acknowledged Haitian freedom with a procession to the African Meeting House. Inside, the group celebrated the Haitians, with Williams spearheading a toast to President Boyer of Haiti. The Columbian Centinel printed his toast:

May the wisdom of his Counsels, the skill and equity of his government, and the sublime virtues of his private life, secure to him the splendid popularity of Washington, and transmit his name with equal lustre to the most distant ages as the Father of his Country.

In August 1828, Domingo served as Chairman of the Committee of Arrangements for a public dinner held in honor of Prince Abdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori, who was freed after 40 years of enslavement and welcomed in Boston before his return to Africa. During this dinner, Domingo proclaimed (as recorded in the Columbian Centinel):

May the Slave-Holders of the world be like the whales in the ocean, with the thrasher at their back, and the swordfish at their belly, until they rightly understand the difference between freedom and slavery.

His words made it into Southern newspapers and caused alarm, with a Natchez, Mississippi newspaper calling the toast an “awful and bloody threat” because it “[asks] that ‘the slave holders’ should be put to the sword.” Over 30 years later, the December 5, 1862 edition of The Liberator recalled Williams’ toast, declaring:

Had Mr. Williams lived till this day, he would have beheld its fulfilment; for between the armies of the North, and the black soldiers of the South, the monster must soon sink beneath the fiery waves of a world’s indignation.

Williams was such a popular caterer and community member that his name made it into Lucretia Peabody Hale’s 1888 book, An Uncloseted Skeleton, almost 60 years after his death. Her book, set in the early 1830s, was described as, “charmingly reflective of Boston society tone and movement.” The mention of Domingo in this book, in conjunction with the newspaper mentions above, demonstrates his prominence in Boston’s social circles.

Despite his accomplishments, if not for the 2005 archaeological dig behind the African Meeting House, Domingo Williams’ life might have been forgotten. During the summer of 2005, an archaeological research team from the University of Massachusetts, Boston carried out excavations in the backlot of the African Meeting House. Over a period of seven weeks, approximately 38,000 artifacts were collected.

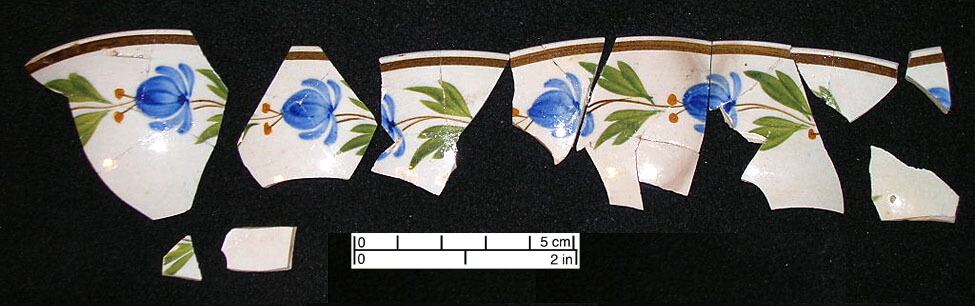

The artifacts date almost entirely from 1806 to 1840, with the greatest number coming from the period that Domingo occupied the basement apartment. The especially large quantity of broken ceramic plates, bowls, and teacups likely reflect the many community dinners held at the Meeting House and suggest that Williams’ successful catering business was based at his home in the building.

Thousands of fragments of ceramics that were recovered were from the same or similar sets of dishes. These matching fragments have been interpreted by archaeologists as Domingo’s efforts to replace broken dishes with identical or near-identical pieces. During this time in the nineteenth century, maintaining a matching set of dishware was a priority only for wealthy households. Purchasing large quantities of matching dishware and frequently replacing broken pieces was difficult, even if funds were plentiful. These artifacts are proof of the demand for Domingo’s services, his high standards, and the pride he took in his work.

Domingo Williams died at the age of 67, roughly a year after moving out of the African Meeting House apartment. His lengthy rental of the apartment and extensive obituary in The Liberator imply that Williams had a long and prosperous career, centered in one of the Black community’s most significant religious, social, and political gathering sites.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Joseph M. Bagley, A History of Boston in 50 Artifacts (Brandeis University Press, 2021); Boston Globe, April 29, 1888; Boston Globe, July 12, 1889; David B. Landon and Teresa D. Bulger, “Constructing Community: Experiences of Identity, Economic Opportunity, and Institution Building at Boston’s African Meeting House,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 17, no. 1 2013; Ed. David B. Landon, “Investigating the Heart of a Community: Archaeological Excavation at the African Meeting House, Boston, Massachusetts,” Andrew Fiske Memorial Center for Archaeological Research Cultural Resource Management Study No. 22 (University of Massachusetts Boston, 2007); The Museum of African American History Boston and Nantucket and The Fiske Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Massachusetts Boston, African Archaeology of the African Meeting House: A Dig and Discover Project in Boston, Massachusetts; National Park Service, Domingo Williams; Smith Court Stories, Domingo Williams.