Dr. and Elizabeth Mott

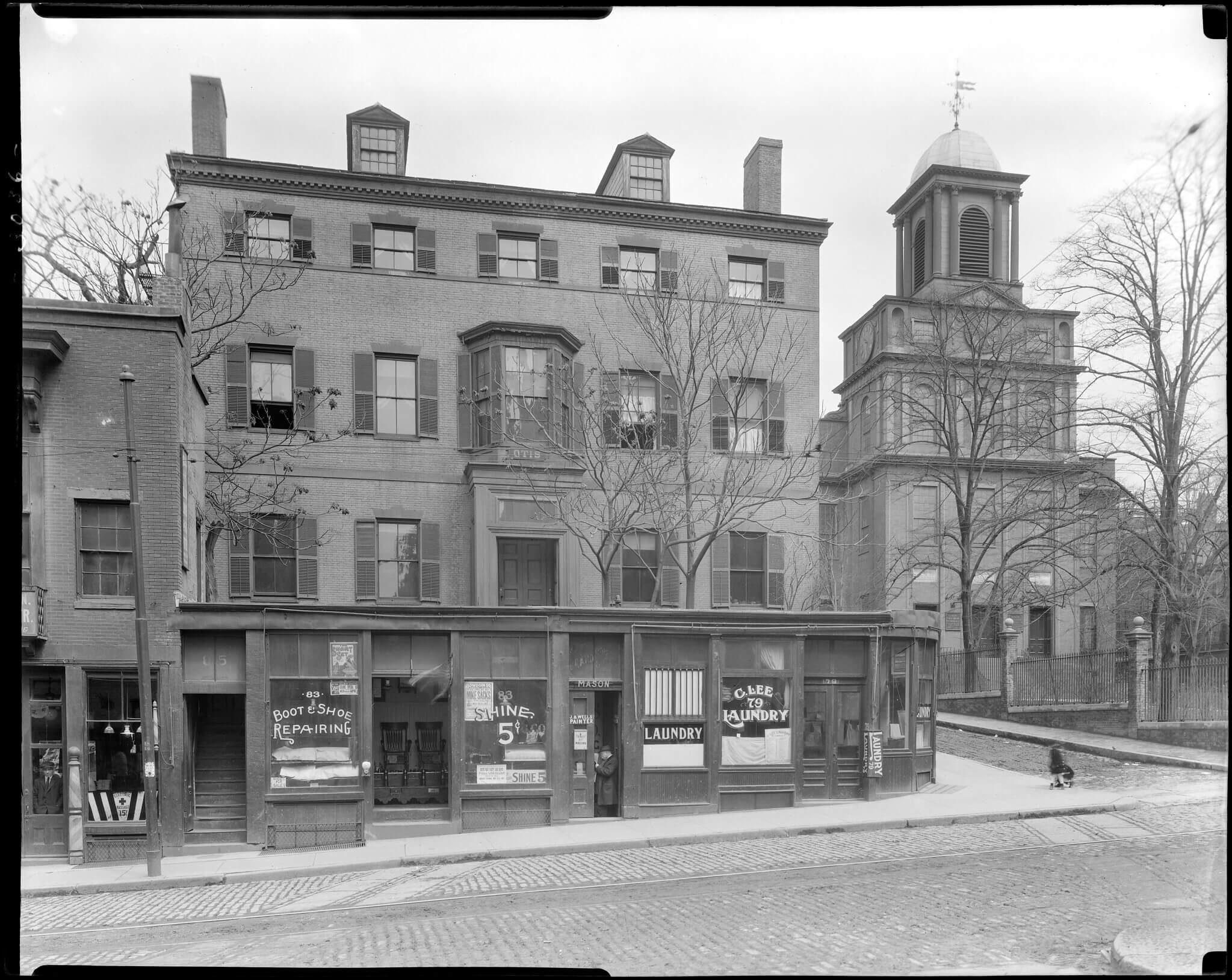

Elizabeth Mott and her husband, Dr. Richard Dixon Mott, were nineteenth-century British immigrants who established a botanical medicine practice at the Otis House, located in today’s West End.

The Motts left England for Boston in 1832, and the following year rented a large section of the Otis House in Beacon Hill. The Otis House was divided into western and eastern halves when it got sold in 1822; the Motts moved into the western part. They needed the space not only to live, but also to practice homeopathy, specifically herbal remedies. This was a popular practice in New England after herbalist Samuel Thomson published many works on alternative medicine in the previous decade. Although homeopathy is no longer widely recommended, some of Boston’s medical practitioners pursued herbal remedies because traditional ones, such as bloodletting, laxatives, or strong chemicals, often made sick patients weaker.

Elizabeth to women and children. The practice was unique because of its “Patented Medicated Champoo Vapour Bath,” which Richard patented months after they moved into the Otis House. This bath involved steam infused with herbs, and modeled popular practices in Europe and Asia, where medicated baths were common. Elizabeth encouraged her patients to pursue diets, rest, massages, and the herbal bath to help cure ailments including rheumatism, as well as chronic illnesses. The practice was not only spacious, it was also comfortable. A notice in the Daily Evening Transcript reported that: “Dr. and Mrs. Mott…have taken, for a term of years, those spacious premises at the corner of Lynde and Cambridge streets, for the reception of ladies who labor under diseases or infirmities. No expense has been spared to make it replete with every comfort and convenience; every bed room will be furnished with medicated baths, suited to the case, if needed, and patients will be enabled to receive, at a minute’s notice medical assistance by night and day. Pledging themselves to keep the establishment select and to conduct it on principles to merit the patronage of the public.”

Although only Richard had a medical degree, Elizabeth Mott did more to promote the work of the practice, and billed herself as a “Female Physician.” In 1834, she wrote The ladies’ medical oracle; or Mrs. Mott’s advice to young females, wives, and mothers, and sailed back to Europe in 1835. Mott’s identity as European was integral to her promotion in America of “European vegetable medicine for the cure of diseases,” and her recommended syrups, ointments, and powders were aimed at curing everything from teething to asthma, even tumors. Richard Mott died shortly after Elizabeth’s trip, but he was cared for by two of her mentees, Harriot and Sarah Hunt. Harriot was the first woman to apply to Harvard Medical School; after she was denied, Harriot fought for women’s access to the medical profession.

When Elizabeth returned from Europe, she moved to New York after struggling to get along with the Hunt sisters. In 1842, she came back to Boston, traveled to cities such as Hartford, Connecticut and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and even saw male patients. In 1847, Mott found a second husband, moved to 40 Cambridge Street, and died of liver disease the year after. The Motts’ lives shaped the West End into a site of medical experimentation, and the Otis House into a space of business.

Article by Historic New England, edited by Adam Tomasi

Source: Otis House Museum, Historic New England, National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites, History of American Women, BU Today, An Annotated Catalogue of the Edward C. Atwater Collection of American Popular Medicine and Health Reform, Volume 3