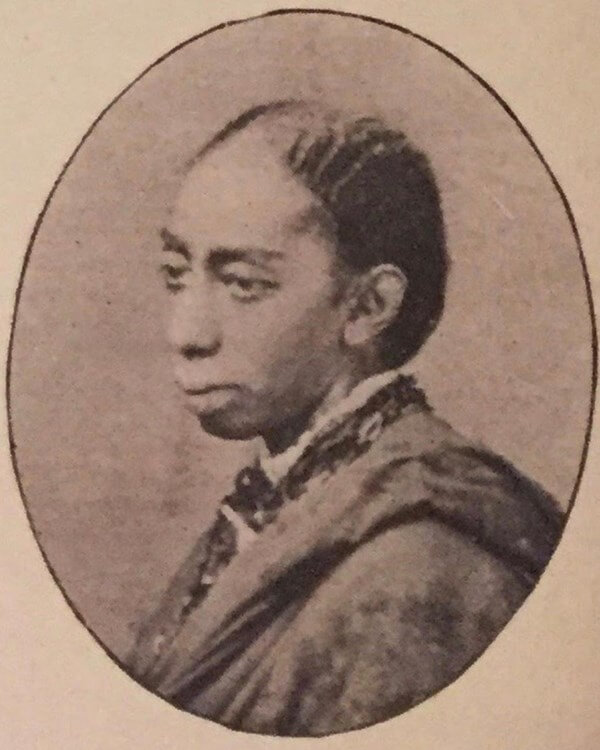

Eliza Gardner: A Life Dedicated to Activism and Service

Raised in a West End home which served as a refuge for fugitive slaves, Eliza Ann Gardner learned the power of social activism at an early age. She dedicated her long life to the struggle for abolitionism, women’s rights, temperance, and still managed to run a successful business. She contributed significantly to the transformation of Black women’s roles in churches and public culture, and served as an inspiration to millions around the world, including her younger cousin, academic and civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois.

Eliza Ann Gardner was born in New York in 1831 to Dorothy and James Gardner. In 1845, when she was fourteen, the family moved to the Black neighborhood of Boston’s West End, the center of the nation’s abolition movement. In their new city James found work as a skilled stevedore, one of a very few Black men to hold this position in the United States at this time. He later employed his own crew and supplied the equipment to move cargo between ships and warehouses. In Boston, both Dorothy and James became very active in the abolitionist movement.

Eliza attended and excelled at the Abiel Smith School, earning several scholarships there. When she was not in school or performing chores, she attended church and learned about the anti-slavery movement through her parents’ activism, reading The Liberator, and from her family’s personal acquaintance with abolitionist leaders such as William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, Lewis Hayden, Wendell Phillips, and Frederick Douglass. The Gardner home at 20 Anderson Street would eventually become a station in the Underground Railroad. Growing up under these influences, it is no wonder Eliza became a vocal activist in her own right.

Given the limited career opportunities for women of color at this time, after her schooling, Eliza entered the dressmaking trade and became a skilled designer and seamstress whose fine needlework was in high demand. She became known for her ability to make connections within her social circles and to find work for women in need. After her parents’ deaths, she turned the home on Anderson Street into a busy workshop, and she also took in boarders. In her spare time Eliza became involved in movements for abolition, human rights, women’s rights, and temperance, but it was in her church that she had the greatest impact.

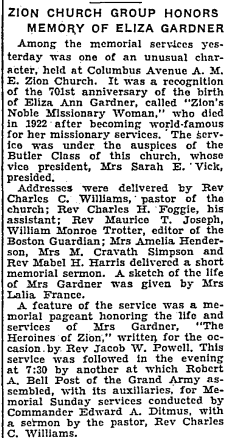

In 19th and early 20th century Boston, Black churches were the most important sites of African American public culture, and the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church, to which the Gardner’s belonged, was central to their social and political lives. Boston’s AME Zion church was formed in 1838 at the corner of North Grove and Cambridge Streets in the West End. Later it moved to North Russell Street and then in 1903 finally settled on Columbus Ave where it still stands today. Prior to the 1870’s, Black Methodist women performed some essential jobs in the church such as fundraising, but they were not formally recognized under church law. Largely due to the work of Eliza and her peers, women would gain rights in the AME Zion Church long before women’s rights were achieved in the American political system.

After years of learning how to navigate church politics from her mother, in 1858, when she was 27, Eliza organized a fundraiser for her congregation and then tried to take on other leadership roles. Though she garnered admiration for her abilities, she was denied any authority by the male leaders of the church. Such treatment inspired Eliza and other women in the congregation to attempt to change church law. They demanded that the governing body remove all wording that prohibited women from having the same rights and privileges as men of the church. They fought for licenses for female preachers, female leadership of missionary societies, the creation of the office of stewardess, and the ordination of women into the ministry. Finally in 1876, female members of the AME Zion Church won the right to vote and hold office, and by the 1880’s women had become licensed preachers, officers in AME missionary societies, and oversaw church governance. These gains might not have been won without Eliza’s tireless striving to transform the roles and rights of women in and outside of the church.

In 1876 Eliza organized the first Zion Missionary Society in New England (later known as the Ladies’ Home and Foreign Missionary Society), an organization that raised funds to send missionaries to Africa. The formation of this society met with resistance from male members of the AME Zion Church who objected to the society’s increased authority. At the church’s 1884 Quadrennial Conference, Eliza eloquently and successfully defended the role of women in the church stating, “I come from Old Massachusetts, where we have declared that all, not only men, but women, too, are created free and equal.” Her strong argument linking the rights of women in the church to the freedoms written into the state constitution was backed by the threat of withholding women’s vital work in the church: “if you commence to talk about the superiority of men, if you persist in telling us that after the fall of man we were put under your feet and that we are intended to be subject to your will, we cannot help you in New England one bit.”

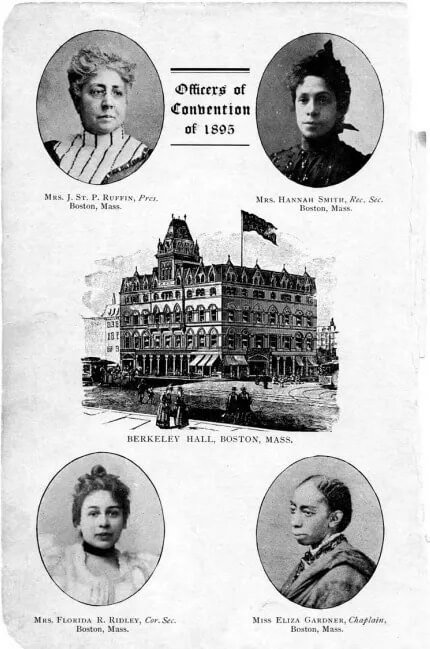

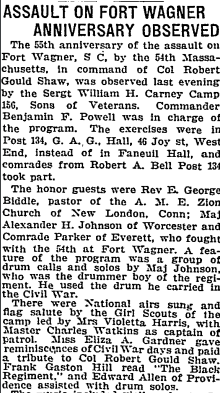

In addition to the leadership roles in her church, Eliza continued to run her business, served as a Sunday school teacher for almost 20 years, and in 1883 became the first woman appointed to the position of Sunday school superintendent for the City of Boston. In 1893 Eliza was one of the 113 founding members of the Woman’s Era Club of Boston, the first Black secular women’s club in the city. She also served as the chaplain and a member of the organizing committee at the founding convention of the National Federation of Afro-American Women in 1895. It was during this time that she would often have her young cousin W.E.B. DuBois, then a Harvard graduate student, over for Sunday dinners. Eliza became a major influence on the young man, and acquainted him with her activist and religious circles.

In her seventies, Eliza moved from Anderson St. and purchased 42 Irving St. where she continued her work and took in boarders. She remained a popular public speaker, and in 1918, at the age of 87, she wrote the history of her church, A Historical Sketch of the A.M.E. Zion Church in Boston. In 1922, Eliza died at the age of 90, having never married or had children. The Gardner Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church in Springfield, Massachusetts is named in her honor.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Boston Globe, Boston, Massachusetts, Wed, Dec 05, 1900 · Page 4; Boston Globe, Boston, Massachusetts, Mon, Dec 11, 1905 · Page 14; Boston Globe, Boston, Massachusetts, Mon, May 23, 1932 · Page 13; Brown, Hallie Q. Homespun Heroines and Other Women of Distinction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.; Jones, Martha S. All Bound up Together : the Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900. Chapel Hill :University of North Carolina Press, 2007.; Jones, Martha S. Vanguard : How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. New York, NY :Basic Books, Hachette Book Group, 2020.; Lemay, Kate Clarke, ed. Votes for Women!: A Portrait of Persistence. Princeton University, 2019.; National Park Service (https://www.nps.gov/people/eliza-ann-gardner.htm);

Eliza Gardner nps.gov; Unknown Source, Wikipedia; Columbus Ave. AME Zion Church buildingsofnewengland.com; National Federation Afro-American Women conference officers, 1895 nps.gov