For Her Race or Her Sex? Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Women’s Suffrage, and Civil Rights

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin (1842 – 1924) was involved in the abolitionist cause, women’s suffrage, and the fight for equal rights for Black Americans. But due to the shifting politics of the women’s movement, Ruffin and other Black suffragists faced a choice: did they attempt to gain the right vote at any cost or were some political sacrifices too great?

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was a member of Boston’s Black Brahmin community during one of the most tumultuous periods of U.S. history. Born in 1842, she was old enough to participate in the Abolitionist movement in the antebellum period. She lived through the Civil War and the hope of Reconstruction. She continued to advocate for the rights of Black Americans and helped found the Black branch of the expanding Women’s Club movement following Reconstruction. During that time, her husband, George Ruffin, became one of Boston’s first Black city councilors, and the first Black judge in Massachusetts. While he died relatively young, Josephine’s work continued through the First World War and the passage of the 19th Amendment. She thus gained the right to vote before her death in 1924.

Josephine was a leader of women’s activism on Beacon Hill, making her work between 1880 and 1920 of special note. While white Brahmins like Nichols sisters, who lived just a few blocks from Ruffin and her daughter Florida Ruffin Ridley, fought for women’s suffrage, Josephine and her compatriots would abandon it in favor of advocating for integration and civil rights.

The national conversations on race and gender equality had both originated in William Lloyd Garrison’s New England Anti-Slavery Society. Founded in the African Meeting House, Garrison continually pushed his organization to the fringe, expanding the range of acceptable conversation in antebellum America. Originally limited to the fight for freedom for Black Americans, the group quickly involved women and women’s rights as a secondary priority. If every man, black or white, deserved equality, then all women did as well.

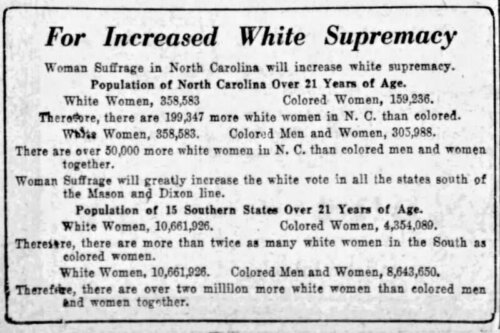

Ruffin was a supporter of women’s suffrage, and led the movement to form a national collection of integrated women’s clubs that would have suffrage as a priority. However, in the late 1890s she began to deprioritize this aspect of her work. The national club movement had become a success, but it was segregated despite Ruffin’s activism. Furthermore, the arguments for suffrage had shifted away from their starting position on the innate rights of women. Between 1880 and 1900 white suffragettes started arguing for women’s votes as a method to reinforce white supremacy in the South and dilute the influence of Catholic and Jewish immigrants in the North. Boston’s Black activists thus faced a difficult decision. Should they prioritize their own suffrage on the basis of these nativist and white supremacist terms? If native-born American women, Black or white, became voters, it would help Black Bostonians keep ahead of the immigrants coming into the city. Indeed, Ruffin herself was anti-immigrant. However, if they agreed with the white suffragist perspective, it would be at the cost of abandoning their Southern compatriots to their underclass status, which left them subject to abuse, lynchings and other violence. Could Black women remain part of a white suffrage movement that excused lynchings by saying they were generally justified?

Ultimately Ruffin and her compatriots decided not to resist suffrage, but to dedicate almost no energy to achieving it. While white women fought for suffrage through the Women’s Clubs, Black women fought to integrate their clubs into the national association they had helped found, and integrate Black people into the rest of American society. Those efforts, ultimately unsuccessful, marked the end of Boston’s abolitionist legacy. As leaders like Ruffin and William Lloyd Garrison Jr. passed away, religious leaders like Thomas Wentworth Higginson lost interest, and Brahmins like Representative (later Senator) Henry Cabot Lodge lost the fight for enshrining civil rights into law, few were left to continue their Black abolitionist legacy. In the following decades Boston’s Black Brahmins would fade away, and its celebrated abolitionists would pass into legend. It would take the work of a new generation, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., to restart a serious movement for racial equality in the United States. Despite King’s and leaders like Malcolm X’s ties to Boston, the city would be slow to adopt the next effort to integrate American society.

Article by Sebastian Belfanti, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Henry Meyer, (1998). All on fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery (1st ed). St. Martin’s Press. ; James M. McPherson (1988). Battle cry of freedom: The Civil War era. Oxford University Press.; Nichols House Museum “Past Exhibits”; Thomas H. O’Connor (1997). Civil War Boston: Home front and battlefield. Northeastern University Press. David M. Potter, (1976). The impending crisis: America before the Civil War; 1848 – 1861 (Don E. Fehrenbacher, Ed.; Repr. [of the] first Harper Colophon ed. 1976). Harper Perennial. Mark R. Schneider, (1997). Boston confronts Jim Crow, 1890-1920. Northeastern University Press.

Images: Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Boston Women’s Heritage Trail

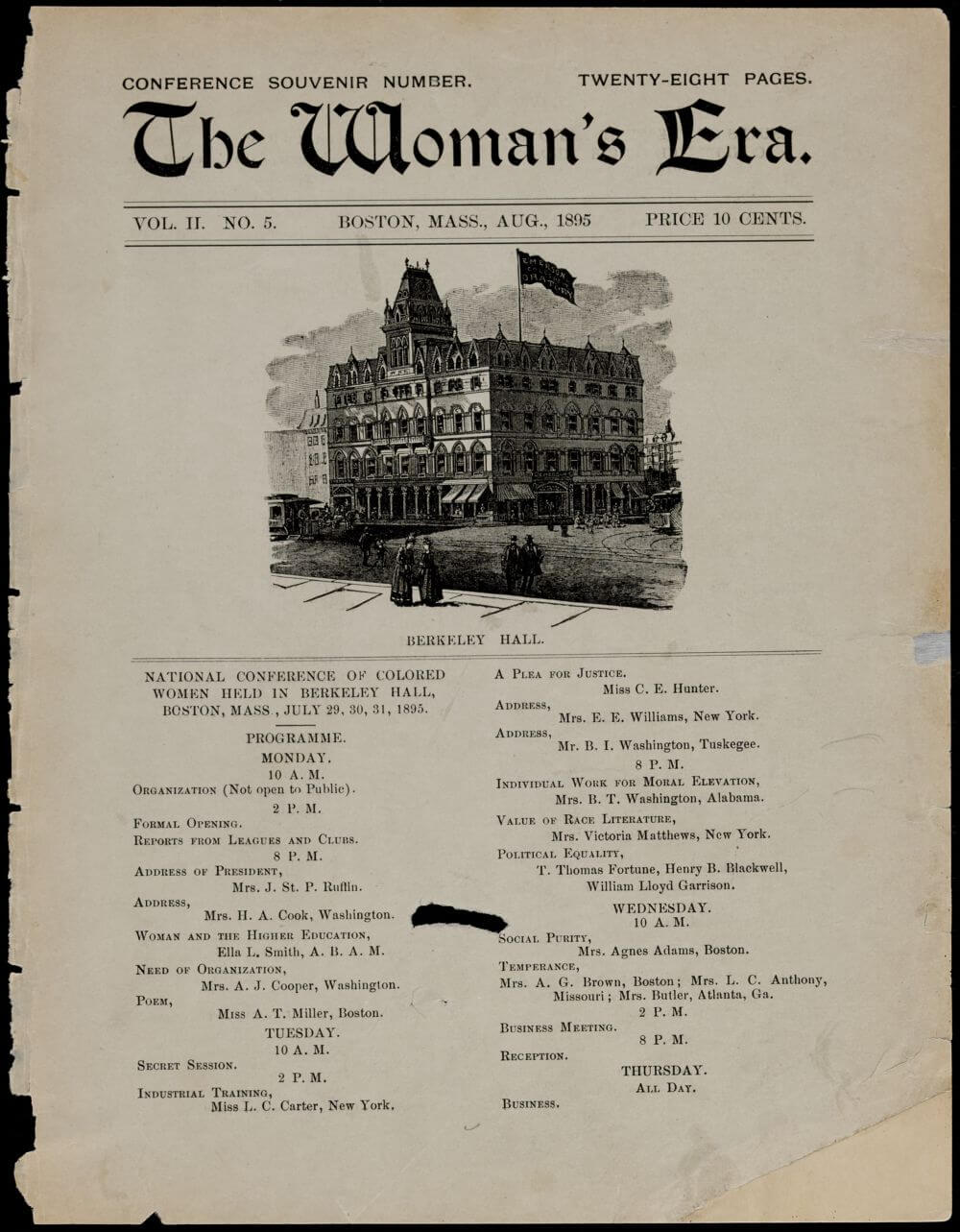

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, ed. The Woman’s Era, Vol II, no. 5, August 1895, Digital Commonwealth

“Just Like the Men” New York Tribune, 3 March 1913, New York Heritage Digital Collections.

“For Increased White Supremacy,” The News and Observer (Raleigh) Sunday, August 15, 1920 UNC Libraries.