Freedom Seekers at the Leverett Street Jail: Polly Ann Bates, Eliza Small, and George Latimer

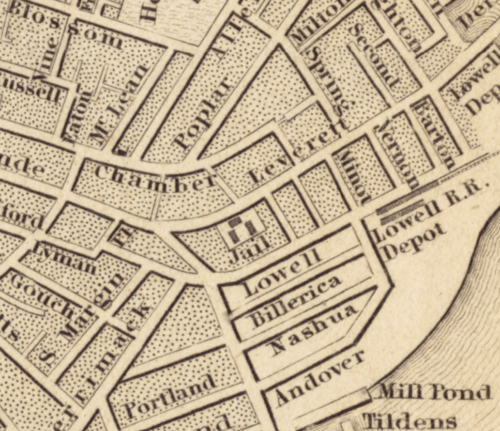

The Leverett Street Jail in Boston’s West End held several freedom seekers whose cases tested the U.S.’s Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, including the cases of Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates (1836), and George Latimer (1842).

After the American Revolution, northern states gradually began to abolish slavery, and freedom seekers escaped to these states in search of refuge. In response, pro-slavery advocates in the South urged Congress to enforce the Fugitive Slave Clause of the United States Constitution. This led to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, which empowered enslavers to capture runaway slaves without due process, and imposed fines and imprisonment on anyone who aided a freedom seeker. In Boston, multiple cases involved this Fugitive Slave Law, including those of Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates (1836), and George Latimer (1842). These three freedom seekers were held at the notorious Leverett Street Jail in the West End, which served as the city and county lock-up from 1822 until 1851.

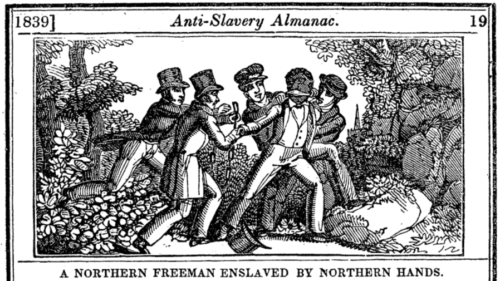

The dramatic courthouse rescue that became known as the Abolition Riot of 1836 was sparked by the imprisonment of two women, Polly Ann Bates and Eliza Small, who were assumed to be escaping their enslaver. The women arrived in Boston Harbor on the brig Chickasaw from Baltimore on Saturday, July 30th of that year. Before the women were able to leave the boat, they were met by Baltimore constable Matthew Turner.

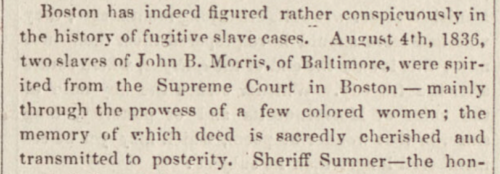

Around the time the Chickasaw had left Baltimore, a wealthy Baltimore businessman, state senator, and slaveowner, John B. Morris, had found out that two of his slaves, known as Anna or Ann Patten and Mary Pinckney, were missing. Morris had hypothesized that the Chickasaw passengers traveling under the names Eliza, or Ann Eliza, Small and Polly Ann Bates were these missing women, and he hired Matthew Turner to capture and return them. Turner, now in Boston, ordered the Chickasaw’s captain, Henry Eldridge, to detain the women, and Turner then went aboard to claim them, and identified the women “from their appearance & the description given of them [by Morris].”

Under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, it would have technically been legal for the agent to seize Polly Ann and Eliza and bring them to Baltimore, but confusion about the need for a warrant in Massachusetts led to the decision to hold the women in custody until a court date could be arranged. Word of the womens’ plight spread among Boston abolitionists and attorney Samuel E. Sewall, an early member of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, was retained as their lawyer. Suffolk County sheriff Charles Pinckney Sumner (father of Senator Charles Sumner) brought Eliza and Polly Ann to the Leverett Street Jail, where according to the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, they were “ministered unto by a few who had not forgotten to ‘maintain the cause of the innocent,’ nor shrunk from the visitation of prisoners.” They would stay in prison for two days.

On August 1, 1836, the women were taken to the Leverett Street Courthouse where their case was heard by Judge Lemuel Shaw. The courthouse was packed with abolitionists. In court, Judge Shaw ordered them freed on a technicality because the agent had not obtained a legal warrant. Following the ruling, the agent requested a warrant so he could rearrest the women and the courtroom erupted in rage. Several people rose up, encircled Polly Ann and Eliza, and made way for the door. An African American woman restrained an officer while the crowd rushed the women out of the courthouse and into a waiting carriage, stunning Judge Shaw and the womens’ pursuer.

Also in the courthouse was the well known abolitionist Thankful Southwick. Decades later, Thankful’s obituary included this anecdote of the day, written by Lydia Maria Child:

The agent of the slaveholders standing near Mrs. Southwick, and gazing with astonishment at the empty space, where an instant before the slaves stood, she turned her large gray eyes upon him and said, “Thy prey hath escaped thee.”

Polly Ann Bates and Eliza Small were never captured and eventually reached Halifax, Canada. No one was charged with their courthouse rescue.

Six years after Bates and Small’s imprisonment, freedom seeker George Latimer was held in the Leverett Street Jail after escaping slavery in Virginia with his wife, Rebecca. On October 18, 1842, enslaver James B. Gray arrived in Boston and forced George’s arrest on a charge of larceny. He was placed in the Leverett Street Jail, and Gray began procedures to return Latimer to Virginia.

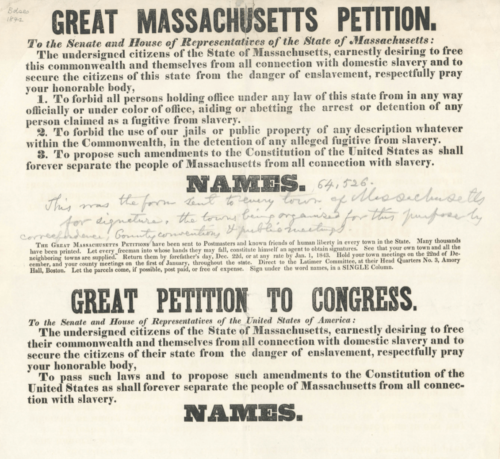

Abolitionists appealed to Judge Lemuel Shaw for his release, but Judge Shaw denied a hearing on Gray’s writ of personal replevin (an action to recover seized individual property). The delay angered protesters, and the Latimer Journal and North Star newspaper was started to report developments in the case. Chaotic rallies were held in Faneuil Hall, and other abolitionists gatherings were held throughout the state, called “Latimer Meetings.” The Latimer Committees issued petitions and collected over 60,000 signatures to free Latimer.

After several weeks of incarceration, George was cleared of the larceny charge. Abolitionists offered to purchase George Latimer’s freedom, and James Gray was so overwhelmed by the furious protesting of abolitionists and confrontation on Boston streets that he accepted. One month after his arrest, George was manumitted for $400 and forbidden from being returned to Virginia by Judge Shaw.

George and his wife Rebecca lived in and around Boston from the 1850s to 1890s, where he worked as a paperhanger. They had four children. The youngest, Lewis Howard Latimer, became a successful inventor and draftsman who worked with Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison on the development of the telephone and the incandescent light bulb.

After purchasing George Latimer’s freedom, Boston abolitionists mobilized to get Massachusetts to pass a law forbidding state law enforcement from participating in the capture and return of fugitives. On March 24, 1843, Massachusetts passed the Personal Liberty Act, also known as the “Latimer Law,” which forbade officials from pursuing, arresting, or detaining fugitive slaves.

Shortly after, included in the Compromise of 1850 was an enhanced Fugitive Slave Law that was a reaction to successful attempts at thwarting the existing law of 1793, as in the case of the Boston Abolition Riot and Latimer Law. The new law mandated that freedom seekers be returned to their enslavers without due process, empowered federal commissioners to enforce it, and mandated the compliance of state and local authorities. In Boston, the 1850 law galvanized local abolitionists to continue to bravely rise to the defense of escaped slaves living in the city, as they had done for Polly Ann Bates, Eliza Small, and George Latimer.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Lyndsay Campbell, “The ‘Abolition Riot’ Redux: Voices, Processes,” The New England Quarterly 94 (2021): 7–46; Asa J. Davis, “The George Latimer Case,” Rutgers; Scott Gac, “Slave or Free? White or Black? The Representation of George Latimer,” The New England Quarterly 88, no. 1 (2015): 73–103; Library of Congress, “Proceedings of the citizens of the borough of Norfolk, on the Boston outrage, in the case of the runaway slave George Latimer”; National Park Service, “The Fugitive Slave Laws and Boston”; National Park Service, “Site of Leverett Street Jail”; Janet M. Schneider, Bayla Schlossberg Singer, Asa J. Davis, and Kenneth R. Manning, Blueprint for Change: The Life and Times of Lewis H. Latimer (New York: Queens Borough Public Library, 1995); Jack Tager, Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2019); Nina Moore Tiffany, Samuel E. Sewall: A Memoir (Boston & New York: Houghton, Mifflin, & Company, 1898).