Frenchy Johnson: From Slavery to Sporting Champion

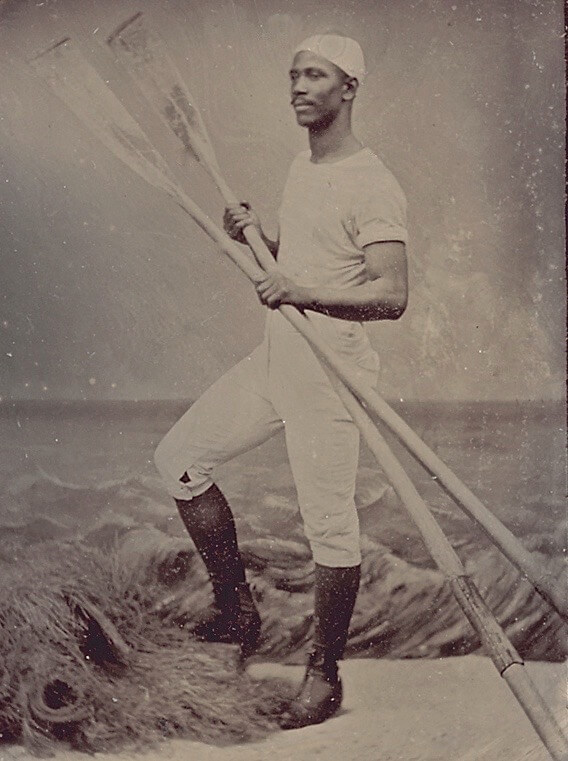

When professional rowing was the biggest sport going, Frenchy Johnson burst out of the West End to become the fastest oarsman in Boston, and among the first African-American athletes to achieve national recognition. And rowing wasn’t even his best sport.

Born into slavery in 1850 in Hampton, Virginia, Frenchy Johnson joined the northern migration of emancipated slaves, settling in the West End in 1867 with the assistance of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Watching the oarsmen in their racing shells pulling back and forth on the Charles River, Frenchy decided that he could do just as well as them. So, in 1875, he and a few friends, including the future pedestrian Frank Hart, got together to form the first-ever African-American rowing club, the short-lived Cornucopia Boat Club. Tom Butler, the long-time Boston sculling champion and president of the West End Boat Club, took notice and became Frenchy’s trainer for his first race against a white opponent. The novice Frenchy handily defeated the professional, an outcome notable enough to be reported in New York on the front page of The Sun, which dryly noted the results of the race between “M. Delowry and a negro named Johnson.”

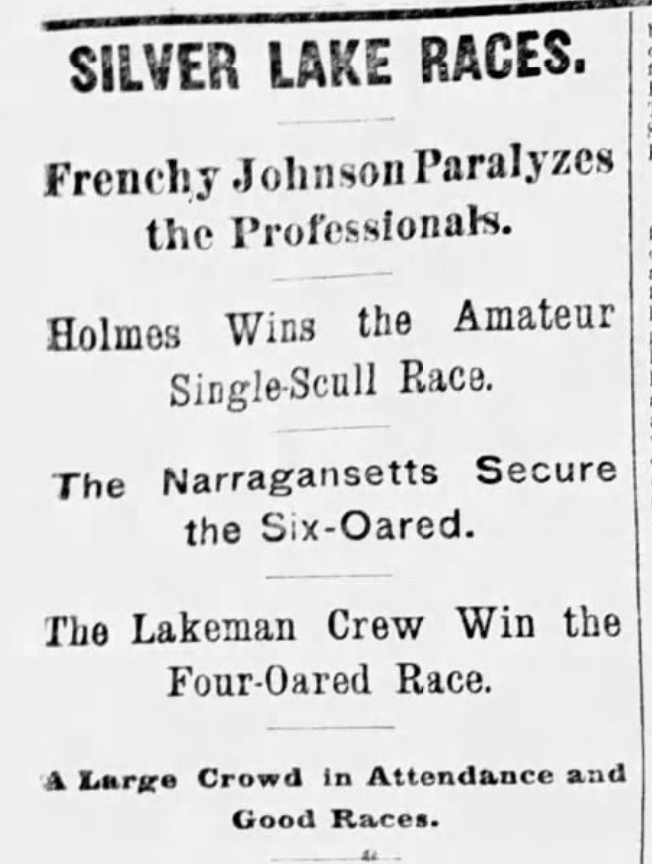

By the 1877 season, he was ready to take on the top scullers in the US and Canada, competing in the professional single scull event at regattas across the Northeast, against well-known oarsmen like Canadian champion Edward “Ned” Hanlan, American champion Charles Courtney, James Riley, Fred Plaisted, James Ten Eyck, George Hosmer, and many others. At the Fourth of July regatta on the Charles River, the crowd of 50,000 spectators “lustily cheered” each entrant, but “the sympathy was mostly with Johnson, who [was] becoming a general favorite among local oarsman,” according to the New York Times. His first big wins came in August 1877, and he would go on to win several other races, defeating James Riley, James Ten Eyck, and others in May 1878, and the July 4th regatta that year. Perhaps his biggest win was the Silver Lake Regatta in August 1878, when he defeated the American champion, Charles Courtney, as well as Riley and others.

Among the professional scullers, Frenchy’s presence wasn’t always warmly welcomed and he was often mistreated; but when he first competed against Courtney in September 1877, they formed an immediate friendship. As that racing season came to a close, it was reported that Frenchy was a guest at Courtney’s home in Union Springs, New York, where he was “enjoying himself with the rod and gun.” It turns out Frenchy was also an expert with a shotgun, and made money selling birds to Boston hotels and eating establishments. He began entering trapshooting competitions by 1879, and as a now-established celebrity, and excellent shooter, these matches became must-see events and the results were reported across the country. A shotgun manufacturer even paid him to use their guns, making him possibly the first African-African sportsman to receive an endorsement deal.

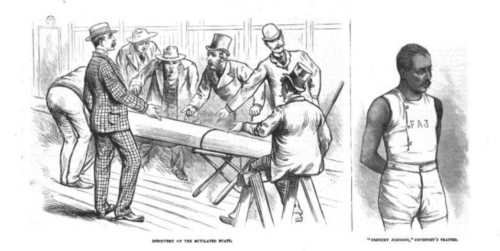

For Courtney’s highly-anticipated match with Hanlan at Lake Chautauqua, New York in 1879, Frenchy served as Courtney’s training partner, while also featuring in sideshows like racing against a steamboat and a glass ball shooting match. The night before the big race, someone sawed Courtney’s racing shell nearly in two. With no suitable replacement, he refused to row, so Hanlan rowed alone and was declared the winner. The fallout was fierce, with both Courtney and Frenchy being accused of sawing the boat to “throw” the race, fueling perceptions that professional rowing was corrupt. They both declared their innocence, but the incident would taint both Johnson and Courtney for years afterward, and their relationship would never be the same.

In 1880, Frenchy began to show signs of tuberculosis. After a brief but eventful career that took him as far as Ottawa, Canada and Jacksonville, Florida, Frenchy Johnson retired from rowing. He died on January 27, 1883, leaving behind a legacy as the greatest Black oarsman, and trapshooter, of the 19th century.

Article by Eric Gordon, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Rowing & People of Colour: A Few of the Few; The Inter Ocean, “Won Fame With Oars,” March 6, 1898, p. 40; Boston Globe, “Frenchy Johnson’s Prospects for Next Season,” October 21, 1877, p. 5; Boston Globe, “The Silver Lake Races,” December 29, 1878, p. 4; Boston Globe, “The Winner,” April 27, 1879, p. 5; Boson Globe, “Death of Frenchy Johnson,” March 19 & 20, 1883; Evening Auburnian, “Frenchy Johnson Shows His Tongue,” August 12, 1879; Jamestown Daily Journal (NY), October 13, 1879; The Sun (NY), October 14, 1875 p. 1; The Standard (Syracuse, NY), June 9, 1879; Marriage Certification and Freedmen’s Bureau Document (Eric Gordon); Trapshooting Hall of Fame email correspondence (Eric Gordon).