Harriet Bell Hayden

Harriet Hayden was born enslaved, fought for her freedom, and aided hundreds of southern escapees by housing, feeding, and protecting them. She did this all while raising a family, running a boarding house, learning to read and write, and becoming an activist and community leader. Without her efforts, the many accomplishments of her husband, Lewis Hayden, would not have been possible.

Harriet Bell Hayden was born enslaved on a Kentucky plantation in 1816. At around age twenty she had a son, Joseph, and at the age of 26 she married Lewis Hayden, who was also enslaved in Kentucky. In 1844, with help from abolitionists Calvin Fairbank and Delia Webster, they escaped, staying in Ohio and Michigan briefly before crossing into Canada. However, they quickly returned to the United States, drawn back by the urge to help others self-emancipate.

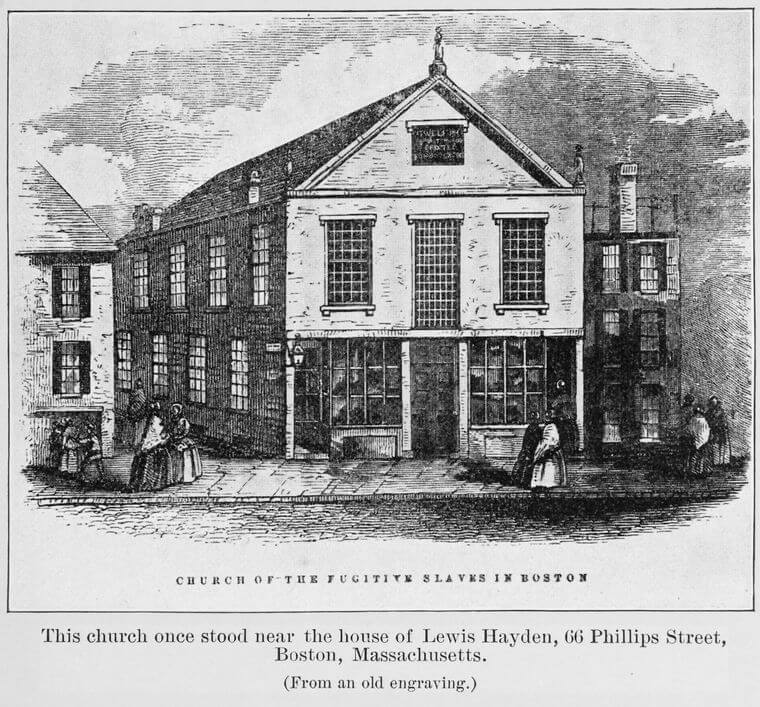

Upon their return in 1845, Harriet gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth. In 1846, the family settled on the north slope of Beacon Hill at 66 Southac Street (later Phillips). Lewis opened a clothing shop on Cambridge Street and became active in the abolitionist movement. The Haydens converted their home into a boarding house and sheltered new arrivals to Boston. Soon, the home became a vital center for Black community life and a safe-house stop along the Underground Railroad, earning it the nickname the “Temple of Refuge.”

The U.S. census of 1850 listed thirteen members in the household at 66 Southac: Lewis and Harriet; their teenage son, Joseph; their young daughter, Elizabeth; an Irish domestic servant; two male tailors; three men who likely worked in the Hayden clothing shop; a cook; and the fugitives William and Ellen Craft. The Haydens would later host and become central to the rescues of Shadrach Minkins (1851) and Anthony Burns (1854). In 1859, John Brown stayed in the Hayden home while preparing for his raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

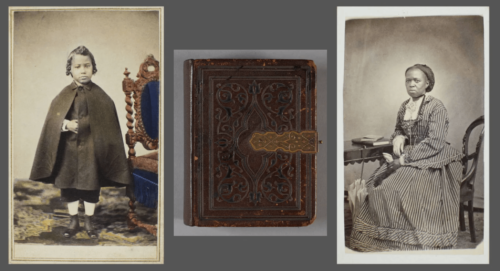

While Lewis became a prominent business owner, community leader, and member of the executive committee of the Boston Vigilance Committee, Harriet provided the often unseen labor necessary to support her family, home, and the community. Largely responsible for the welfare of all members of the household, she courageously faced the dangers of sheltering those being hunted under the Fugitive Slave Act, while also running a boarding house and caring for children. Two photo albums gifted to Harriet in the 1860s by Robert Morris (one of the first Black lawyers in the US) and Dr. Samuel Birmingham (an abolitionist) allude to Harriet’s status in and connection to Boston’s intellectual and activist communities. During this time, she also took reading and writing classes with Apphia Howard, a White abolitionist.

In 1923, the politician John Edward Bruce remarked:

Few black men could have done what Mrs. Hayden did in those stirring times. She had all of a woman’s tact, persistence and cleverness in emergencies, and was conveniently deaf, dumb, and blind when necessary and hence she was not a popular nor useful aid to U.S. marshalls nor Southern masters hunting their runaway slaves in Mass

After the Civil War, the Hayden home continued to be a busy boarding house, meeting place, and Black refuge. Harriet was also involved with many social causes and organizations. In 1875, she co-founded the Prince Hall Auxiliary Association to provide a space for female family members of the Prince Hall Masons, and led the association in raising funds for a new masonic lodge. In 1876, she organized a celebration for Black Bostonians for the centennial of the American Revolution. And, in 1887, Harriet was a founding member of the West End Woman Suffrage League.

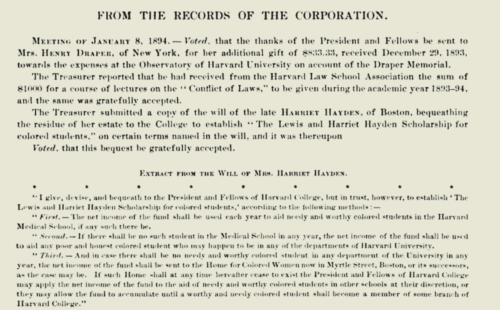

Harriet Hayden died in her home in 1893, four years after Lewis. In her will, she left $5,000 to Harvard Medical School to establish the Lewis and Harriet Hayden Scholarship for Colored Students for “needy and worthy colored students in the Harvard Medical School.” It is believed to be the first and only university endowment given by a former slave. The HMS Hayden scholarship continues today.

The Lewis & Harriet Hayden House is a private residence on Boston’s Black Heritage Trail and is listed as a site on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Boston Athenaeum: The Harriet Hayden Albums; Boston Globe, December 27, 1893; Jacqueline Jones, No Right to an Honest Living; The Struggles of Boston’s Black Workers in the Civil War Era (Hachette Book Group, 2023); National Park Service; Shirley J. Yee, Black Women Abolitionists: A Study in Activism, 1828-1860 (University of Tennessee Press, 1992).