How the West End Shaped U.S. Contract Law

The West End played a key role in defining the U.S. jurisprudence surrounding the execution and maintenance of contracts set out in the U.S. Constitution in two major cases: Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge & Fletcher v. Peck.

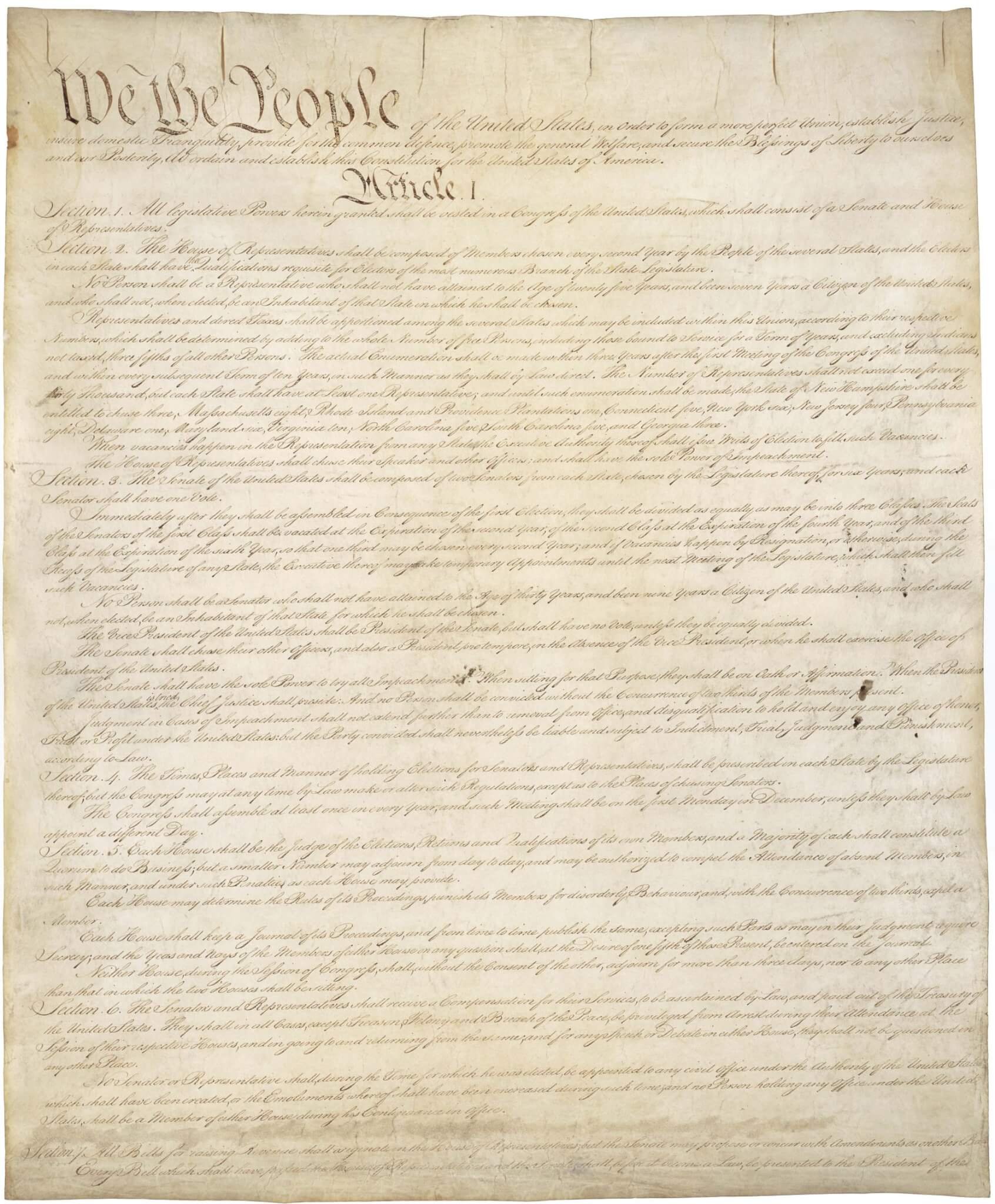

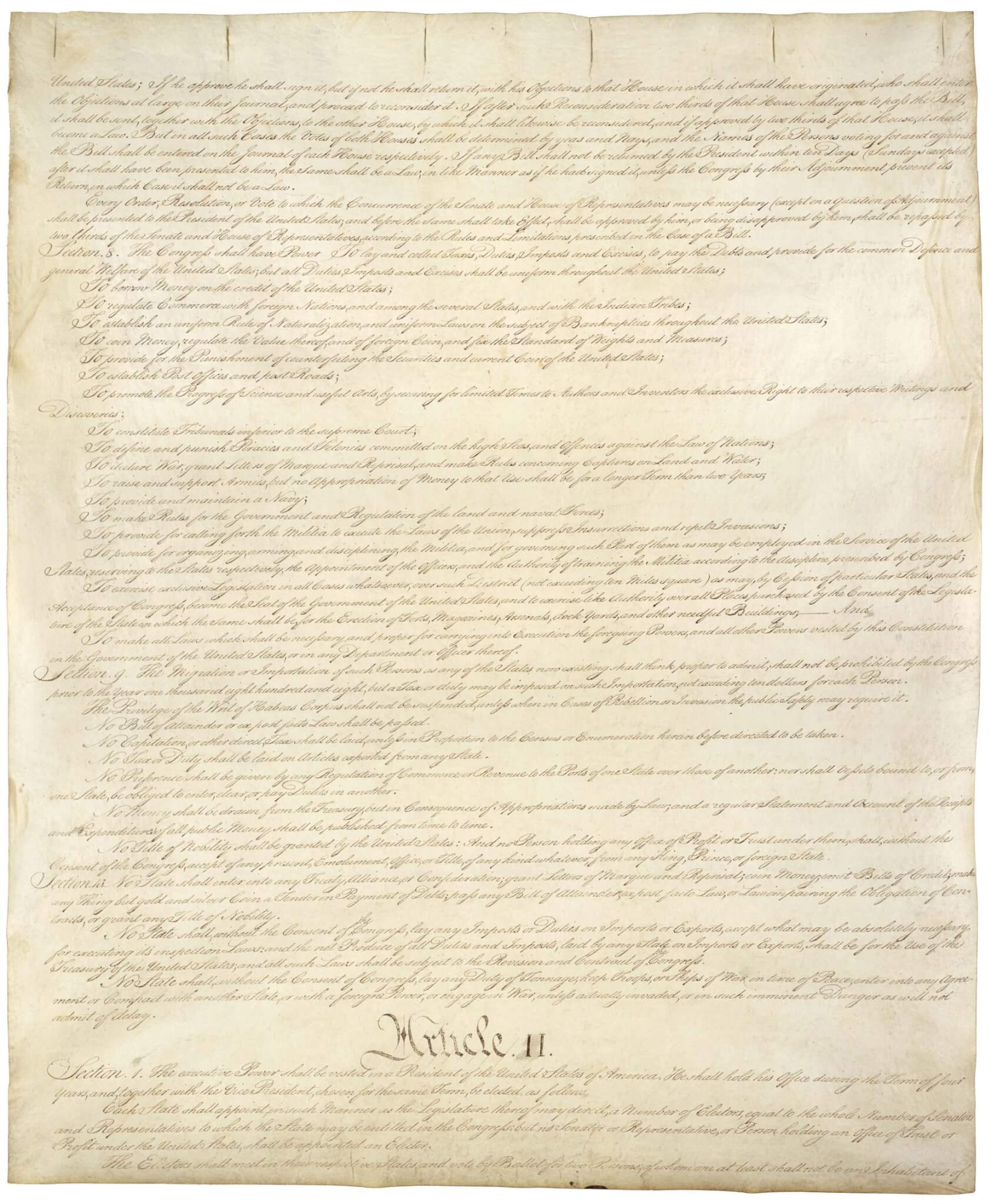

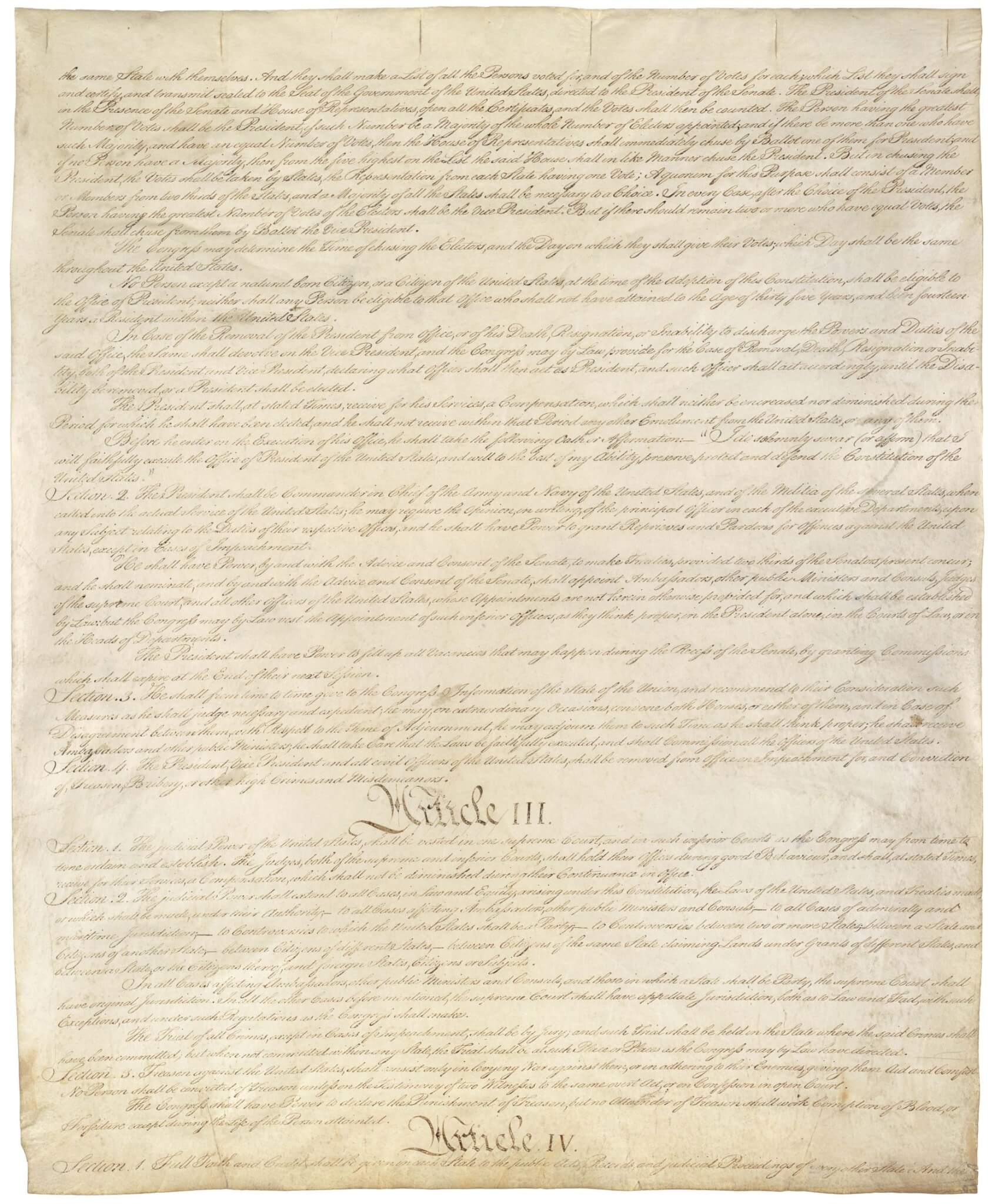

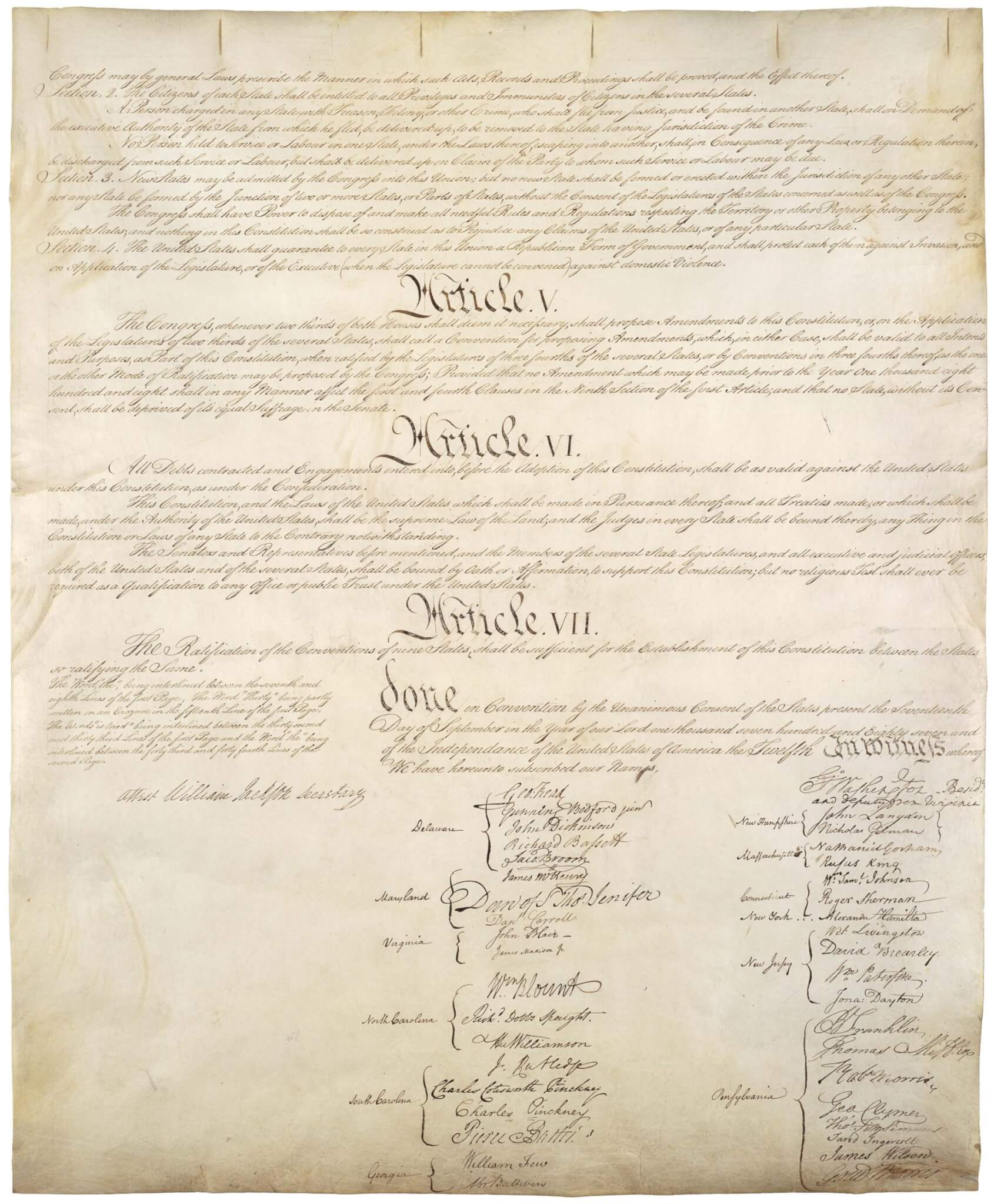

The West End of Boston played a key role in building the jurisprudence that defines the U.S. Constitution’s Contract Clause (Article 1, Section 10, Clause 1). The Contract Clause protects individuals from intrusion by state governments, keeps states from encroaching on the federal government’s powers, and is a fundamental element of the modern socioeconomic system of the States.

For all law in the United States, while guidelines are laid out in legislation and the Constitution, most practical implementation comes through court rulings. These rulings clarify points of confusion and address the interpretive nature of law. To avoid excessive variation in interpretation, courts are expected to consider the past rulings of all relevant courts – U.S. courts in the relevant jurisdiction, along with some English Common Law, etc. The collection of historic decisions, theories and opinions make up the jurisprudence that guides interpretation of American law.

Two court cases involving the West End played a major role in defining the Constitutional law surrounding contracts: Charles River Bridge vs. Warren Bridge and Fletcher vs. Peck. Both cases were heard by the Supreme Court, and are integral to the modern understanding of contractual obligations in the United States.

Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge

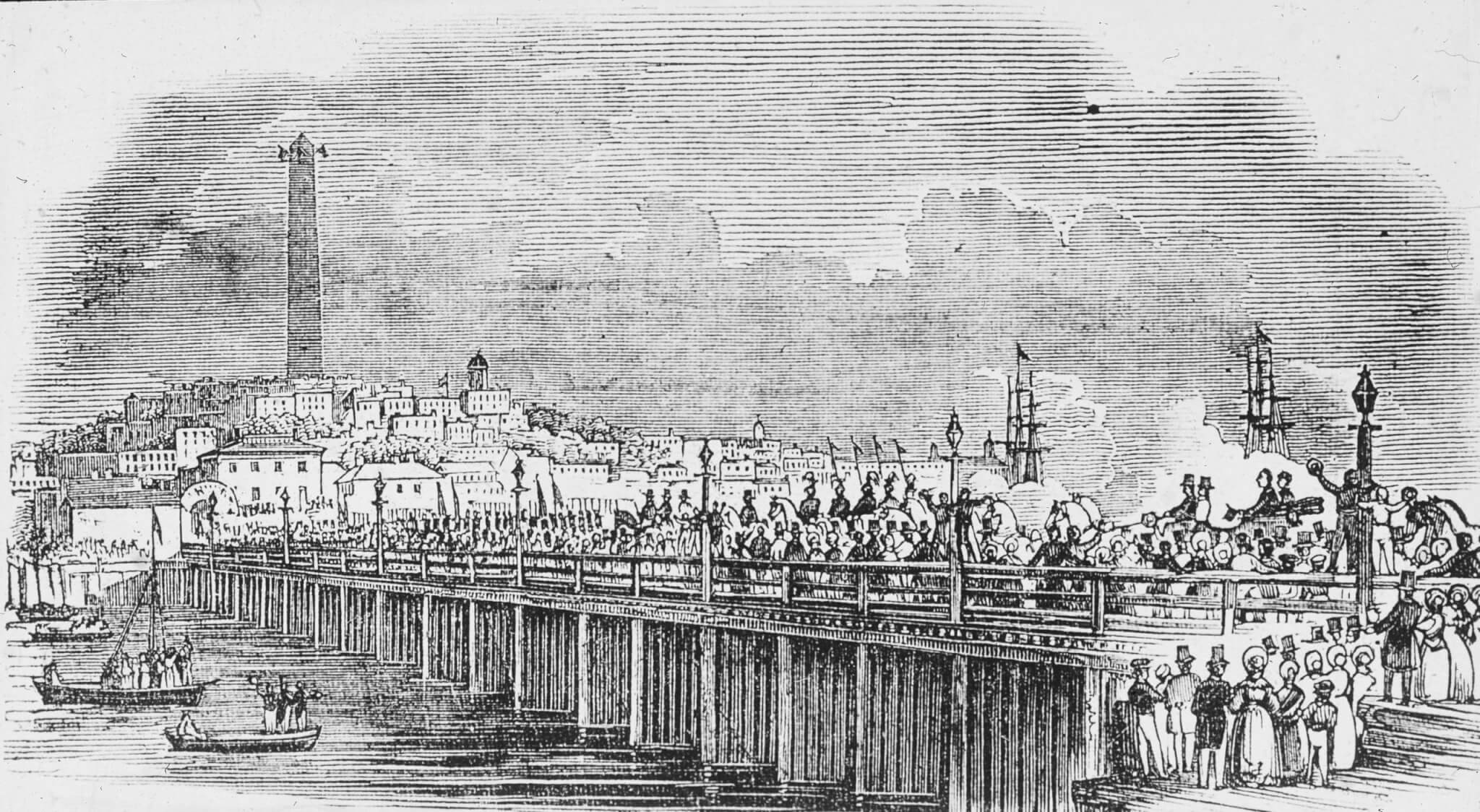

In 1785, the Massachusetts legislature granted a charter to the Charles River Bridge Company to construct a bridge connecting the West End with Charlestown – then a separate town from Boston. The Charles River Bridge Company (led by Harrison Grey Otis) funded the construction and, once built, collected toll revenue on the passage, which cut down freight travel between the towns of Charleston and Boston from a seven-mile journey to less than one mile. The bridge was immediately successful and immensely profitable, but despite enormous profits the company kept the tolls high, angering much of the public that depended on the bridge as a critical economic artery.

In the 1820’s, public dissatisfaction, combined with a large population increase, led Massachusetts to approve the construction of additional bridges, granting the Warren River Bridge Company a charter to construct a second bridge across the Charles in 1828. Built near the CR Bridge, the Warren River Bridge was to be toll free once its construction costs were paid and an agreed upon profit was reached. In 1837, with its profits threatened, the Charles River Bridge’s owners filed a suit with the U.S. Supreme Court against the Warren Bridge proprietors, claiming the legislature had defaulted on its initial contract.

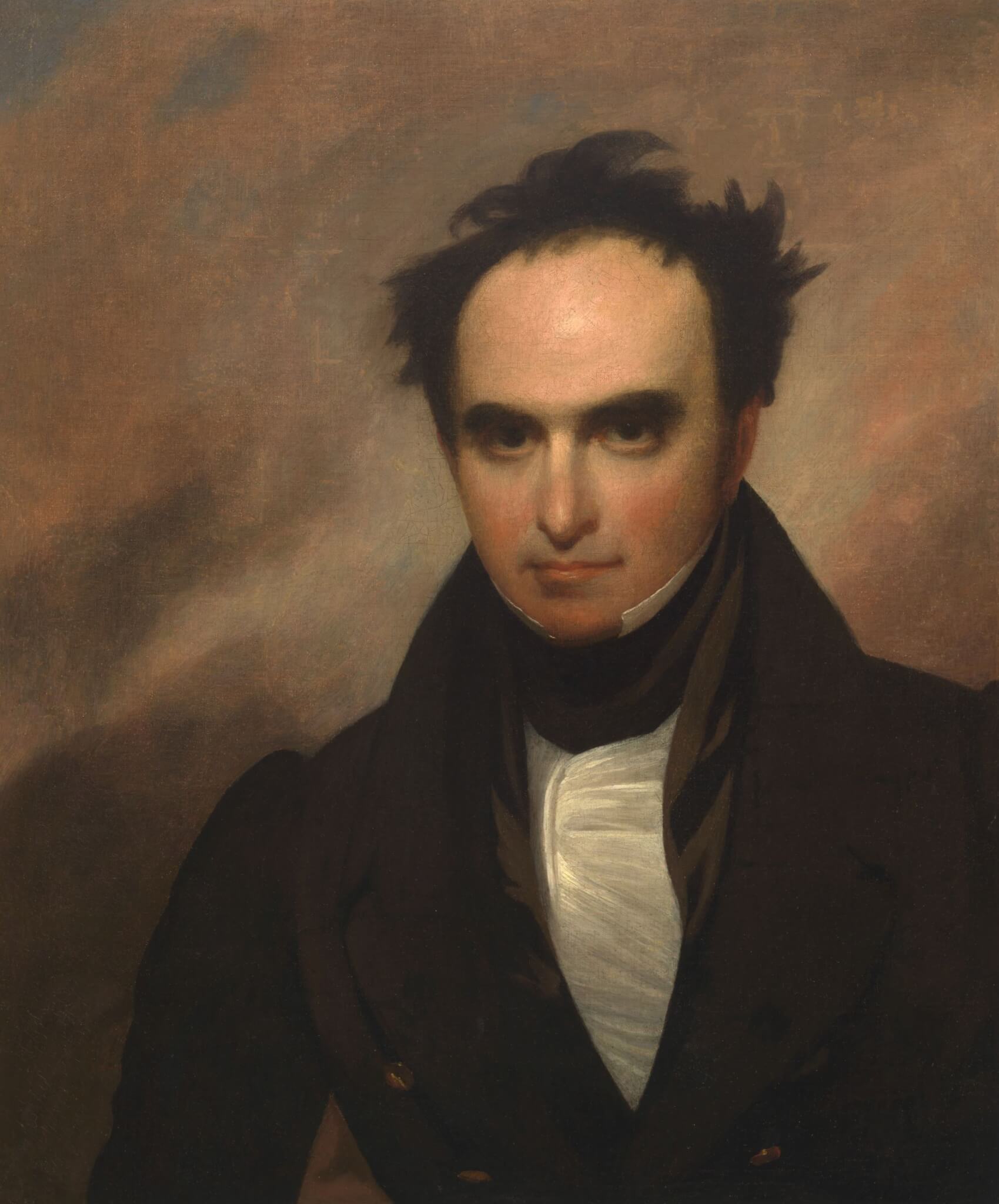

The plaintiffs used their considerable resources and connections to hire Daniel Webster to present their arguments. Webster, about halfway through a career that would include 223 Supreme Court cases, turned out to be a poor choice. His immense influence over the court – forged through close friendships with Judges Story and Marshall – was greatly reduced after Marshall’s death the previous year. The new Democrat-appointed Chief Justice, Taney, was fast becoming a pain for Webster, a Whig, who could no longer rely on a court that agreed with his opinions by default.

In a 5-to-2 decision, Chief Justice Taney ruled that there was no violation, and that the legislature had not given “exclusive control over the waters of the river (sic) nor invaded corporate privilege by interfering with the company’s profit-making ability.” It further found that “community interest in creating new channels of travel and trade” took “priority” over the rights of private property entities to generate profit.

The ruling immediately gained importance beyond all expectations. A ruling in favor of the Charles River Bridge Company would have set a precedent that the dozens of privately incorporated toll roads crossing the northwestern U.S. had precedence over new routes. Insignificant when foot and horse were people’s only options, this ruling ultimately ensured that railroads wouldn’t be forced to argue for their right to improve established routes in the coming decade.

Fletcher v. Peck

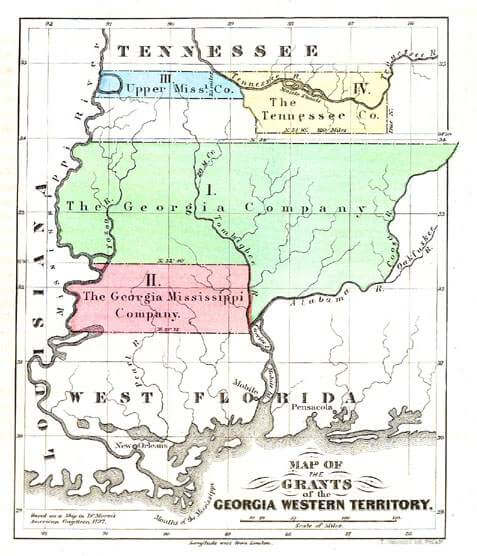

In 1795, Georgia’s state legislature granted 35 million acres of land to private speculators at low cost. However, the following year it was revealed that most of the legislators voting for the grant were bribed, and the legislature voided the grant. Meanwhile, Massachusetts investor John Peck had purchased some of this land, and subsequently sold 13,000 acres to another speculator, Robert Fletcher, while the 1795 act was still in effect.

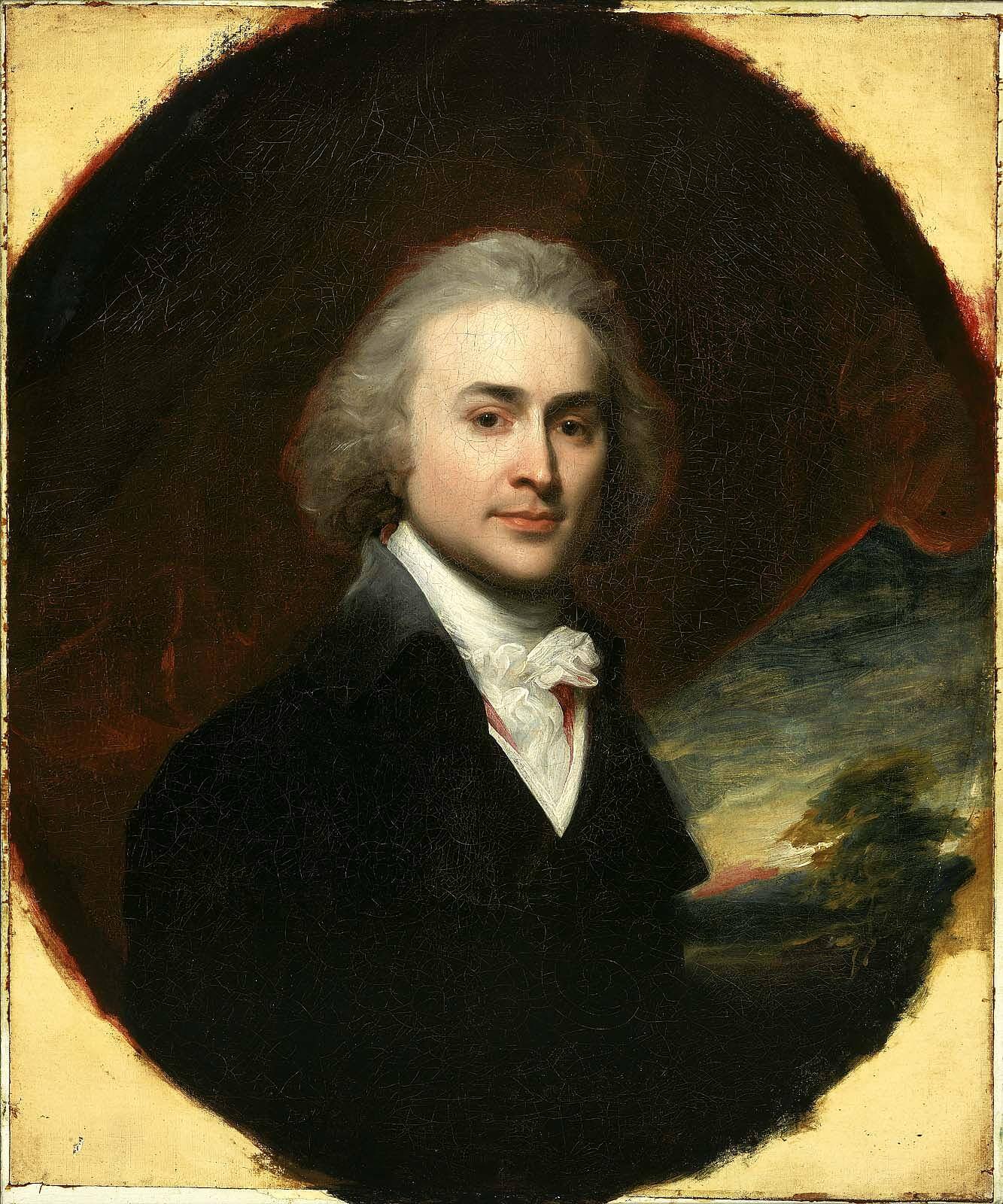

In 1803, Fletcher learned that state law had voided the sale. He alleged that Peck had no legal right to sell the land and brought a suit against him, claiming that Peck did not have clear title to the land when he sold it. Peck hired John Quincy Adams as his attorney, who before he became the nation’s sixth president, had a law office in Scollay Square.

Adams argued Fletcher v. Peck before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1809, and the case was ruled on the following year (by then, Adams had become America’s first minister to Russia). In its decision the court ruled in Peck’s favor, finding the state of Georgia did not have authority to void the 1795 grant because the U.S. Constitution forbids states from passing laws interfering with contracts. The sale was a binding contract, which under the Constitution’s Contract Clause, couldn’t be invalidated even if legally secured.

Fletcher v. Peck was the first case in which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a state law on constitutional grounds.

Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge and Fletcher v. Peck are two of the most important rulings in defining jurisprudence for the U.S. Constitution’s Contract Clause. The Constitution states that the federal government guarantees contracts, but it is a living document that can change over time, and required extensive interpretation in the early republic.

Article by Susan Gilbert, edited by Sebastian Belfanti & Lois Ascher