James Bowdoin II: A Man of Science and Power

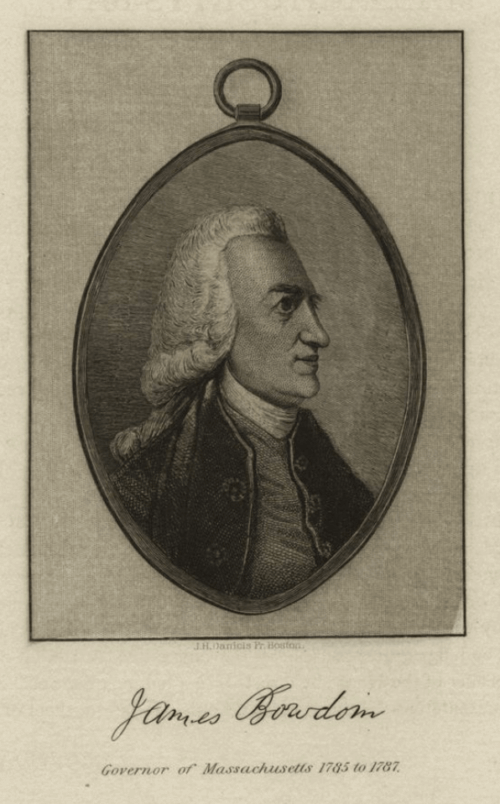

James Bowdoin II, scientist, politician, businessman and the namesake of the West End’s Bowdoin Square, embodied the powerful gentry class of his day.

Family Background and Early Life

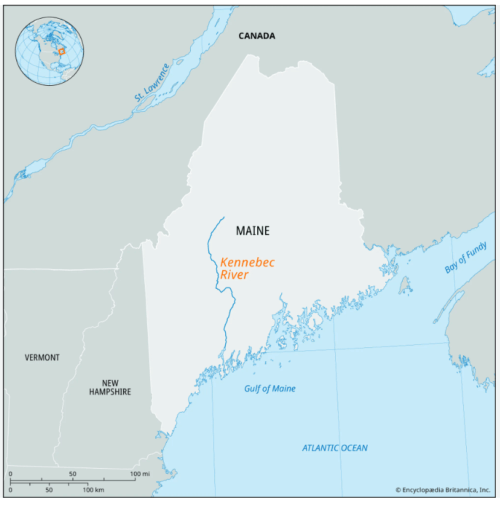

James Bowdoin II was born in 1726 to James Bowdoin I and his second wife, Hannah Portage. The elder Bowdoin traveled to Boston with his French Huguenot father, Pierre Baudoin, who left France for Ireland, crossed the Atlantic to Maine, and finally settled in Massachusetts to escape the violence between native tribes and European colonists. James Bowdoin I made his fortune in maritime trade, building a small fleet of merchant ships, and through land investments along the Kennebec River in Maine, then part of Massachusetts. Before his death, he became one of Boston’s wealthiest men, lived in a £10,000 mansion, and served as a judge and a member of the Governor’s council. Young James Bowdoin II thus enjoyed a privileged upbringing. He studied at a grammar school and “exhibited the characteristics of persistence, ingenuity and industriousness.” As was customary for boys of his class, he prepared for and was admitted to Harvard College in 1745.

Intellectual Life

Bowdoin’s passion for intellectual pursuits began under professor John Winthrop IV, descendent of the first governor of Massachusetts and the foremost astronomer in the Colonies. Winthrop exposed Bowdoin to the latest scientific texts and spurred what would become a lifelong interest in astronomy and electricity. While studying at Harvard, Bowdoin met and befriended Benjamin Franklin during the latter’s visit to Harvard. The two would correspond until Franklin’s death in 1790, and Bowdoin even collaborated on Franklin’s electrical experiments for which he (Franklin) won membership into the Royal Society. Because of his lifetime activity as an amateur scientist, Bowdoin was voted in as the first president of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1780, and was also admitted into the Royal Society shortly before his death. In addition to his scientific study, Bowdoin amassed a library of 1,200 books and several hundred pamphlets.

Business Dealings

After his father’s death in 1747, Bowdoin was left a very wealthy man, inheriting “£23,000…1/3 of the Elizabeth Islands off Martha’s Vineyard; a glass factory at Germantown (Quincy); an iron foundry at Bridgewater; two full shares in the Kennebeck Purchase Company, a speculative land company; three brick stores and four houses in Boston, one of the latter valued at £7250; and farms and land at York [Maine], Falmouth [Maine], Barnstable and Roxbury.” Such wealth provided the young Bowdoin and his wife, Elizabeth Erving, whom he married in 1748, the means to pursue whatever life they wished. Bowdoin was quite active in business, pursuing several trading projects like his father, but he was most engaged in land speculation in Maine, where he and his brother controlled “land stretching for nearly one hundred miles along Maine’s Kennebec River, and for fifteen miles into the interior on either side.” The company founded a dozen towns along the Kennebec River, including Bowdoin and Bowdoinham, and promoted European colonization in the area. Bowdoin’s interest in securities exchange led to him being elected the first president of the Massachusetts Bank (forerunner of the First National Bank of Boston), newly formed in 1784.

Politics

As was common among the 18th-century gentry, Bowdoin also had political aspirations. He entered Massachusetts politics in his 20s, first as part of the Boston Town Meeting, then in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. As a member of the General Court (i.e., the legislature), Bowdoin took a keen interest in Native American affairs, which was later key to his business in Maine. By the time he was appointed a Councillor of the Upper House, a prestigious post, Bowdoin was well known as a “king’s man.” He not only supported the existing British colonial government, but had British in-laws, and many friends in the Royal Army and Navy. His political leanings took a turn when he became engaged in a personal dispute with Royal Governor Francis Bernard. A firm loyalist before the end of the Stamp Act Crisis in Boston, Bowdoin allied himself with the radical party of John and Samuel Adams and James Otis, who, like him, wanted an end to Bernard’s governorship.

A Revolutionary

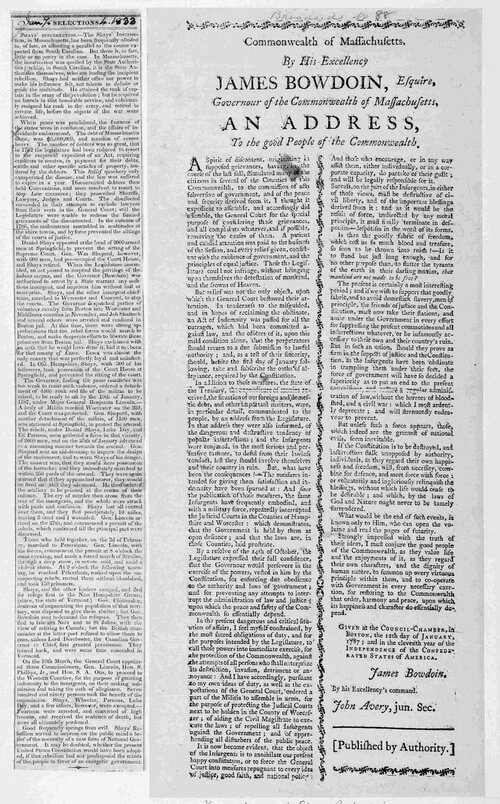

By 1768, Bowdoin was an accepted member of the Revolutionary camp, and edited the well-known and highly inflammatory account of the Boston Massacre, Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston. Though Bowdoin was chosen as a delegate to the first Continental Congress in Philadelphia, he was forced to pass on the honor due to poor health, so he remained in Boston where he led the Boston Committee of Safety up to the dawn of the American Revolution. He served on the council of the Revolutionary state government, and after independence, acted as the President of the 1779 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention that drafted the state’s constitution. Bowdoin’s next political venture was the governorship of Massachusetts. In his first attempt to win the seat, he lost to John Hancock, and it was not until Hancock’s retirement from that post that Bowdoin finally won the election for governor and served in the position from 1785 to 1787.

Mixed Legacy

Bowdoin’s legacy, like that of many powerful men of the 18th century, is marked both by great achievement and troublesome beliefs and behavior. Despite being a staunch backer of Whig political theory, honoring the rights of man and freedom from tyranny, he owned slaves throughout his life and never emancipated any. While serving in the Massachusetts legislature, Bowdoin maneuvered himself into a position with then-Governor Shirley to negotiate a treaty with the Wabanaki tribe of Maine, who were fighting to maintain some of their ancestral land, land which was largely under the control of Bowdoin and his Kennebeck Purchase Company. The treaty allowed for the building of forts, supported by Bowdoin, which cut off the Wabanki from their hunting and fishing grounds, and served as bases of military operations used to decimate the tribe. While serving as Governor, Bowdoin was faced with handling the outbreaks of violence by Worcester-area farmers aimed at the debt courts, known as Shay’s Rebellion. Though praised by conservatives for his quick military response in subduing the rioters, republican-minded voters were critical of Bowdoin’s harsh fiscal policy and severe military action against Shay and his supporters. Subsequently, Bowdoin lost the 1787 gubernatorial election, most likely due to this reaction.

Bowdoin Memorialized

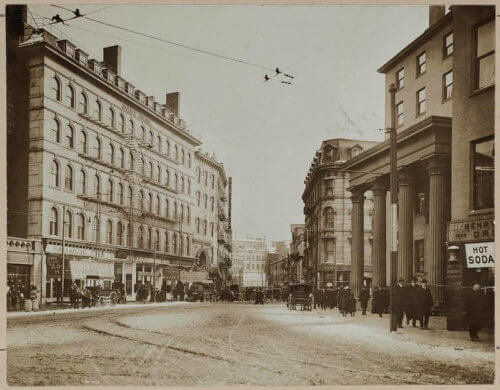

James Bowdoin died on November 6, 1790 of “a putrid fever and dysentery.” Despite his harmful opinions and actions, James Bowdoin II is immortalized as one of early America’s most accomplished amateur scientists and an important leader of its independence movement. He is the namesake of the prestigious Bowdoin College, founded in 1794 in Brunswick, Maine. It was initially endowed both financially and with gifts to Bowdoin’s collection of art and scientific instruments by Bowdoin’s son, James Bowdoin III. The former governor’s name is also used daily by Bostonians who frequent Bowdoin Square in the West End, or travel through the Bowdoin MBTA station.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Bowdoin College, Museum of Art; Gordon E. Kershaw and Mooz, Peter R., “James Bowdoin: Patriot and Man of The Enlightenment,” Museum of Art Exhibition Catalogues. 76 (1976); https://www.bowdoin.edu/about/history-traditions/historical-sketch.html;

https://shaysrebellion.stcc.edu/shaysapp/person.do?shortName=james_bowdoin;

https://bowdoinorient.com/2022/04/01/james-bowdoin-promoted-settler-colonialism/; http://www.famousamericans.net/jamesbowdoin/; Rob Hardy, “James Bowdoin: Philosopher and Politician,” The New England Quarterly 84, no. 4 (2011): 696–708; https://www.masshist.org/.