John Brown

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, intended to spark a violent uprising by enslaved people against their oppressors, was preceded by Brown’s efforts to acquire recruits and financial support. He received some assistance from abolitionist Lewis Hayden, who lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill with his wife, abolitionist Harriet Hayden.

The north slope of Boston’s Beacon Hill was home to many preeminent abolitionists in the nineteenth century, particularly Lewis and Harriet Hayden at 66 Phillips (Southac) Street. The Haydens escaped from slavery in Kentucky during the 1840s, and they turned their home into a safe house for the Underground Railroad. From the home, Harriet had also run a boarding house for newly free African Americans. In 1858, Lewis was the first African American appointed to the position of messenger for the Massachusetts Secretary of State, with an $800 annual salary. This role allowed Hayden to forge significant connections with the state’s political leaders, which bolstered his contributions to Boston’s abolitionist movement. Hayden worked as the Secretary of State’s manager for thirty years, earning the nickname “old philosopher” in the State House, until his death in 1889. The West End Museum has previously covered the historical impact of Lewis and Harriet Hayden (February 2021), though an additional layer to the Haydens’ history deserves new attention: abolitionist John Brown’s visit to the Haydens’ house, shortly before his raid on the Harpers Ferry armory in Virginia (now West Virginia) in 1859.

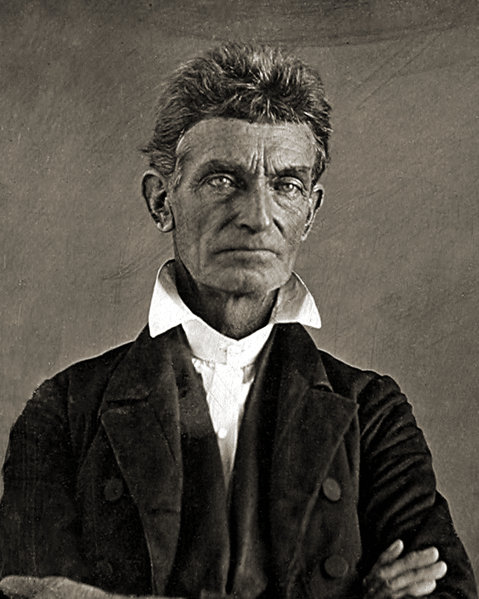

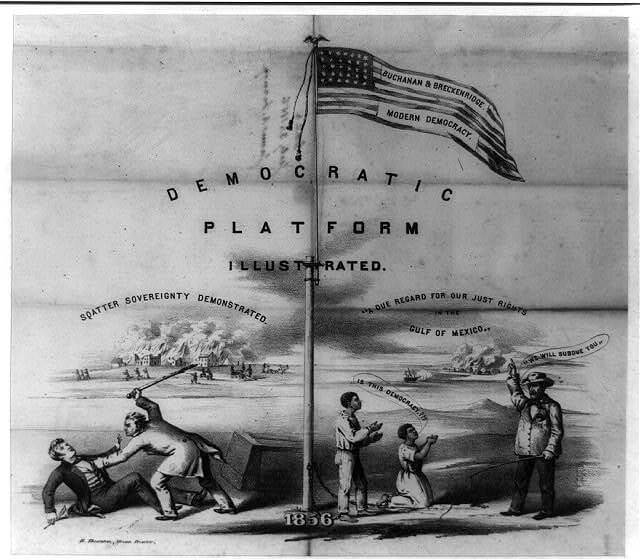

Before John Brown, a white man born in 1800 to a religious, anti-slavery family in Connecticut, became a widely-known abolitionist, he frequently changed jobs and suffered many failed business ventures (in tanning, canal building, agriculture, and land development) that led to his personal bankruptcy in 1842. But his anti-slavery principles were a constant, even if his profession was not. In 1854, he moved with his five sons and son-in-law to Kansas to join roughly 3,000 other free soil, free labor, anti-slavery and abolitionist New England settlers relocating to the state with financial support from Abbott Lawrence, John Murray Forbes and other Boston Business Leaders of the New England Emigrant Aid Society and Massachusetts State Kansas Committee. These groups, and many private individuals like Brown, wanted to be residents for an upcoming referendum on slavery in Kansas prompted by Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which established that the newly organized Kansas and Nebraska territories would decide by popular vote whether to become free or slave states. Violent confrontations between pro-slavery and anti-slavery advocates in both states, which Brown and his sons participated in, were in many ways a foreshadowing of the Civil War. In fact, some historians view “Bleeding Kansas” as the functional start of that larger conflict.

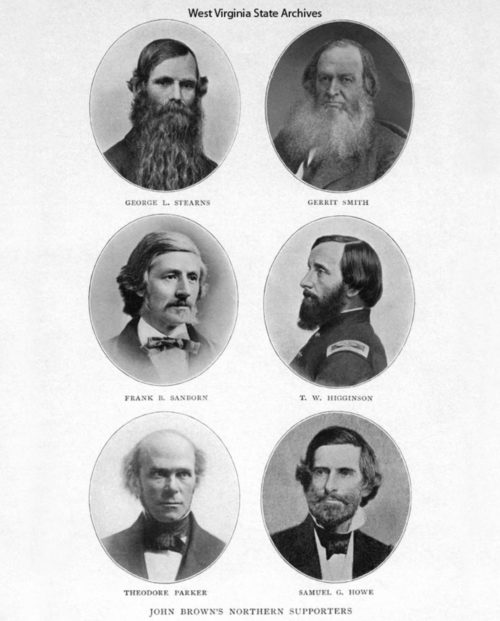

John Brown increasingly believed that only a violent uprising, predominantly by enslaved people themselves, against slavery could end the oppressive institution once and for all. In 1858, he began crafting plans for a raid on Harpers Ferry, the federal armory in West Virginia, in order to steal the guns stored there and put them in the hands of enslaved people for a wider rebellion. The raid required recruits and financial assistance, and John Brown busily met and communicated with abolitionists. In early 1858, after spending a month at Frederick Douglass’ home (from January to February), Brown visited Boston to discuss his plans and solicit financial help from abolitionist leaders. He had arrived in Boston earlier for this purpose, visiting the city seven times between 1857 and 1859. While in Boston Brown spent some time staying at Lewis and Harriet Haydens’ home, and later commended Lewis for being one of the “men of action” he admired. Brown would also gather other find other Boston “men of action” in his “Secret Six”, wealthy men sympathetic to the anti-slavery and abolitionist causes who helped to fund his excursion into Virginia, and were ultimately the subject of a Congressional investigation.

Lewis Hayden played a small role in the Harpers Ferry raid, recruiting six free Black men to participate (only one of whom could make it to West Virginia in time, though he did not participate in the fighting). Hayden also received an important letter in October 1859, either from Brown or his son John Brown, Jr., requesting financial support for Brown and his men assembled in Pennsylvania. Hayden by chance ran into Francis Merriam, the grandson of the treasurer of Boston’s Vigilance Committee (which assisted fugitive slaves), and told Merriam, “I want five-hundred dollars and must have it.” Merriam replied, “If you have a good cause, you shall have it.” Hayden told him of John Brown’s plans, and Merriam offered not only money, but also his own participation in the raid, telling Hayden, “If you tell me John Brown is there, you can have my money and me along with it.” The enthusiasm by which Francis Merriam, and other recruits, joined the raid demonstrated that Brown and his radical strategy became increasingly popular. Hayden, for his part, hoped that Brown might succeed but believed that violence was usually unhelpful. Hayden believed, in the words of historians Stanley and Anita Robboy, that “a strategy that would transform slaves into citizens would require more profound changes than those won through violence.” Despite his mixed feelings, Hayden would be recognized as one of multiple contributors to John Brown’s raid with the publication of F.B. Sanborn’s “The Virginia Campaign of John Brown” (1875) in The Atlantic Monthly.

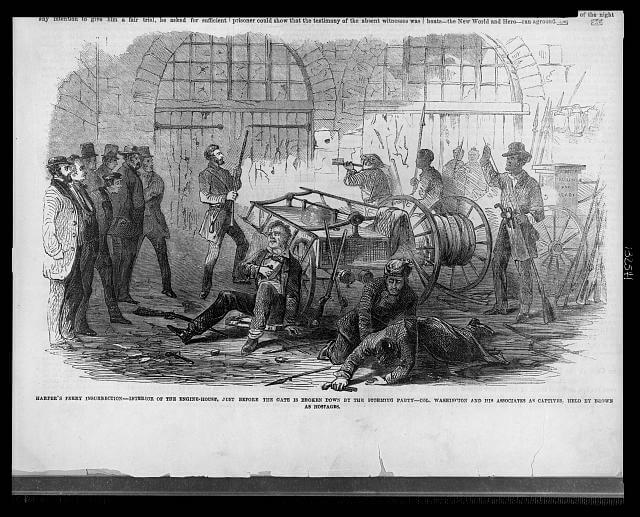

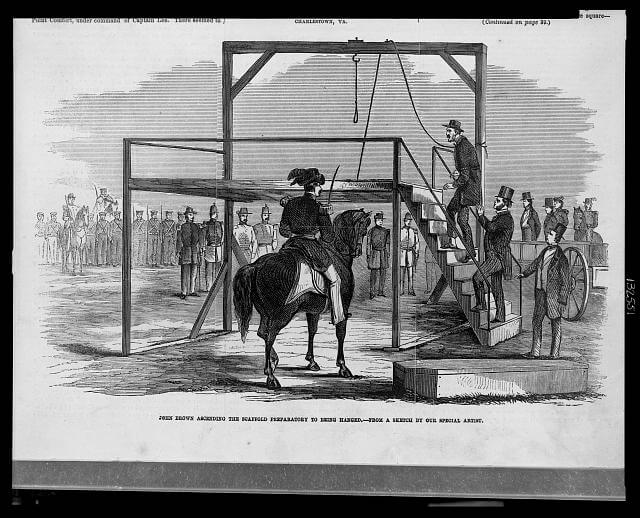

Brown’s use of violence was occasionally successful, prior to the Harpers Ferry raid that ultimately failed. In December 1858, Brown managed to free eleven enslaved people in Missouri, and ensure their safe arrival in Canada, after killing their master. But many abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass (one of Brown’s contemporaries) and John Brown himself to an extent, believed that the Harpers Ferry raid was a suicide mission. On October 16, 1858, Brown led an interracial group of men in a raid that quickly failed. Although they successfully took over the armory at nighttime, Brown ordered that his group wait inside the armory until enslaved people came to join them. When this did not transpire, locals had sufficient time to circle the armory, force Brown’s surrender, and kill some of the participants in the raid. John Brown was eventually executed on December 2, 1858, and his last words again foreshadowed the Civil War: “I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood. I had…vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.”

Although John Brown’s raid was a failure, it would not have taken place without support from the thriving abolitionist networks, emanating in part from the north slope of Beacon Hill, which we credit today for helping break the chains of slavery throughout the United States. After his death, Brown became a martyr for anti-slavery and militant abolitionists throughout the Northern States. He and his raid became the subject of a popular song sung by soldiers marching off to war. It was this song that was sung by the Massachusetts 6th, the first Union regiment of the Civil War, as they marched to defend Washington D.C. in the opening days of the conflict.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: Clio; National Park Service; The Atlantic; National Archives; Stanley Robboy and Anita Robboy, “Lewis Hayden: From Fugitive to Statesman,” The New England Quarterly 46:4, December 1973; Secretary of State of Massachusetts (“Lewis Hayden and the Underground Railroad”); PBS; West End Museum; Civil War Boston, O’Conner; The Impending Crisis, Potter; Cotton and Capital, Abbott