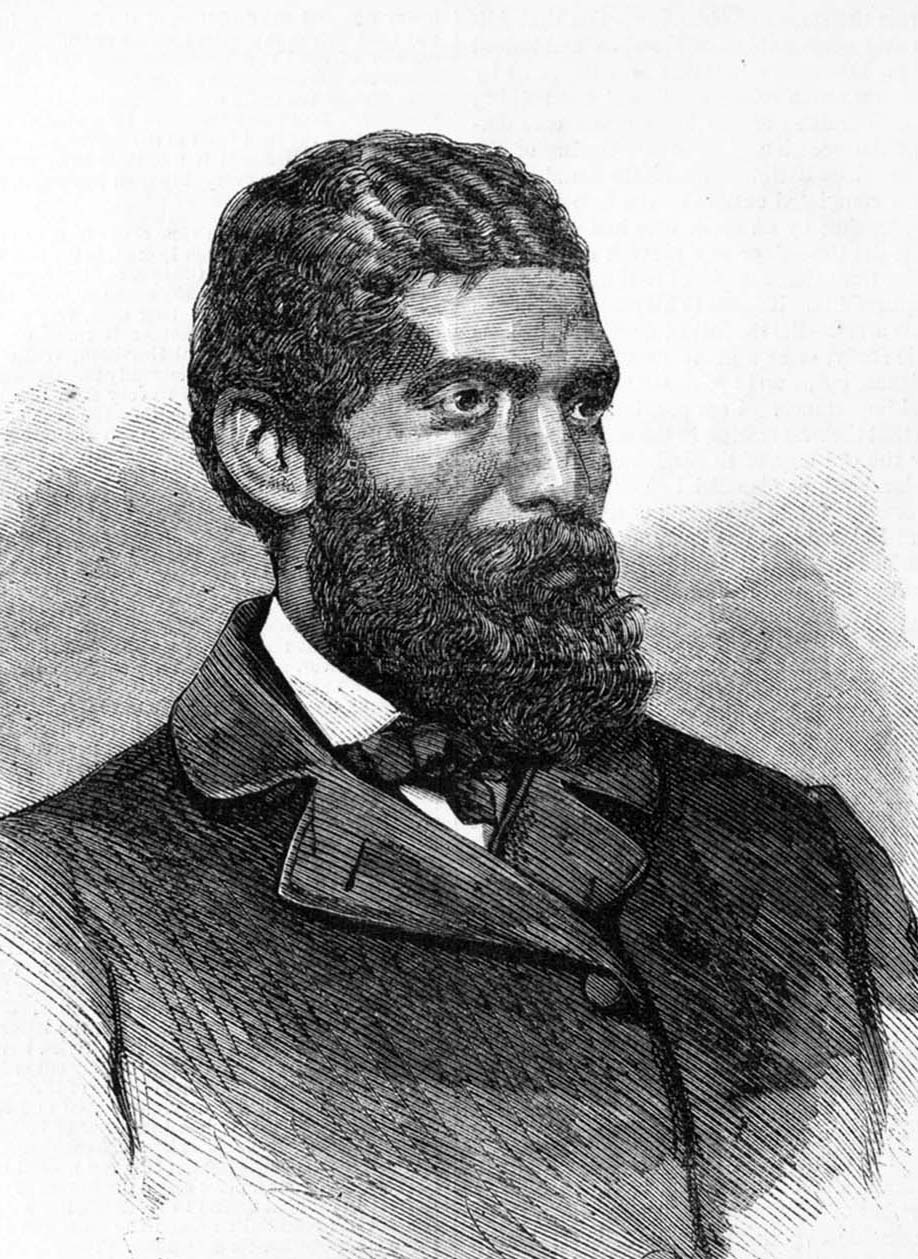

John Rock

John S. Rock was an accomplished Black dentist, doctor, lawyer, and abolitionist lecturer who resided on the north slope of Beacon Hill shortly before and during the Civil War.

On October 13, 1825, John Swett Rock was born in Salem, New Jersey to free Black parents. Because Rock read many books as a child, his parents kept him in school until he turned eighteen, in order to foster his intellectual curiosity. At nineteen, Rock became a public school teacher and taught in Salem, NJ from 1844 to 1848. While teaching, Rock wanted to become a doctor; two doctors in the area offered him their private libraries to study medicine and complete an apprenticeship. But medical schools in New Jersey would not admit Rock simply because he was a Black man. Rock then turned to dentistry, and excelled at it, because American dentists did not need formal degrees to open practices in the nineteenth century. Rock moved to Philadelphia, PA in 1850 to open a dentist’s office in the city where the then-largest free Black population in the North resided. The following year he received an award from professional colleagues for his skill at making false teeth. After briefly directing Apprentices’ High School, a night school for Black residents, in 1851, Rock was allowed to take classes at Philadelphia’s American Medical College and graduated with an M.D. in 1852.

Rock arrived in Boston, MA in 1853, and resided at 83 Philips Street on the north slope of Beacon Hill, part of the old West End neighborhood and the center of Boston’s free Black community prior to the Civil War. While continuing his professions of medicine and dentistry, Rock participated with many other Black Bostonians in the abolitionist movement. While pursuing his studies for yet another profession, law, Rock proved his talent as a lecturer throughout New England. In 1856, the Massachusetts legislature invited Rock to deliver his lecture titled “The Unity of the Human Races.” Both the abolitionist press (The Liberator) and a mainstream newspaper (Boston Daily Bee) lauded Rock for his rhetorical abilities and the quality of his arguments. As a prolific anti-slavery lecturer, Rock traveled to Washington, D.C. in 1861, after the Civil War began, to deliver a lecture titled “A Plea For My Race.” Abolitionists faced hostile crowds even in the nation’s capital, where hecklers threw various items at Rock during his address.

Rock had a more welcoming audience when he delivered a lecture in January 1862 at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, in Boston, called “A Deep and Cruel Prejudice.” In this lecture, Rock argued for the necessity of allowing Black men to serve in the Union Army in order to defeat the Confederacy and emancipate all enslaved people. Although President Abraham Lincoln previously insisted that his priority was preserving the Union, even if slavery remained, Rock argued that the Civil War made abolition inevitable. He said, predicting Lincoln’s political evolution:

It is true the government is but little more antislavery now than it was at the commencement of the war; but while fighting for its own existence, it has been obliged to take slavery by the throat, and sooner or later must choke her to death. Jeff Davis is to the slaveholders what Pharaoh was to the Egyptians, and Abraham Lincoln and his successor, John C. Fremont, will be to us what Moses was to the Israelites. I may be mistaken, but I think the sequel will prove that I am correct.

Rock’s hope for African-American military service was fulfilled with the Militia Act in July 1862, which allowed for the creation of volunteer Black regiments in the Union Army. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 then authorized the military recruitment of formerly enslaved men in Southern territories occupied by the Union.

While a seasoned lecturer, Rock had already been admitted to the Massachusetts bar, after passing his exam in September 1861. In February 1865, after the end of the Civil War, Rock was admitted to the federal bar when Chief Justice Salmon Chase granted him the right to argue cases in front of the United States Supreme Court. Rock previously reached out to Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, who had strong abolitionist credentials, to correspond with Chief Justice Chase about appointing him to the Supreme Court bar.

Rock soon died of tuberculosis in 1866, but his appointment to the federal bar had a larger significance for racial equality even if Rock did not live to argue a case. Sumner’s assistance in facilitating Rock’s final milestone is noted on the headstone of Beacon Hill’s accomplished Black dentist, doctor, lecturer, and lawyer in the nineteenth century.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Civil War History 26:4 (George A. Levesque, “Boston’s Black Brahmin: Dr. John S. Rock,” December 1980), BlackPast; African American Civil War Memorial Museum; “John S. Rock,” in William Wells Brown, The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (Boston: James Redpath, Publisher, 1863), pages 267-270.