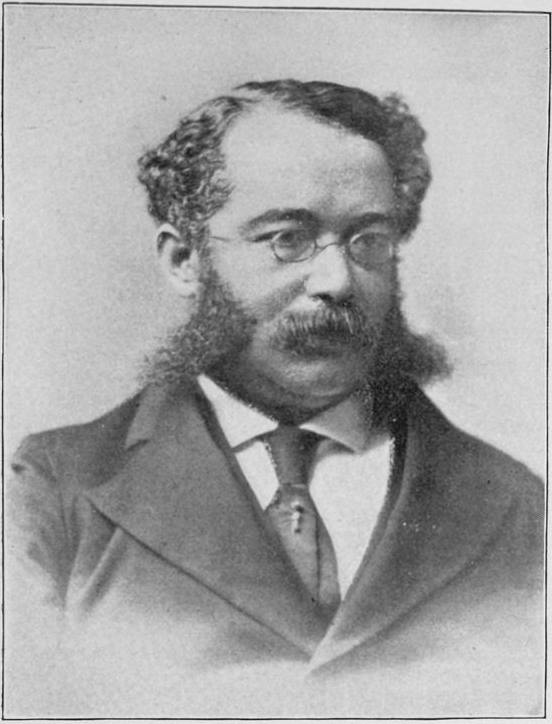

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and George Ruffin

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and George Ruffin were eminent African-American residents of the West End in the late nineteenth-century. Josephine’s newspaper, The Woman’s Era, was published from her home and instrumental to the founding of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896. She was its first vice president.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was a lead organizer of African-American women in Boston and the nation at large. Born in 1842 to a wealthy family, for her father, John St. Pierre, was an eminent tailor, Ruffin experienced discrimination at an early age when a Boston private school turned her away because of race. After graduating from the integrated schools of Salem, Massachusetts and the Bowdoin Finishing School in Boston, she married George Ruffin in 1857. The same year, the two fled to England in resistance of the Supreme Court’s outrageous decision, in Dred Scott v. Sandford, that African-descended people were not entitled to American citizenship, and that slavery was constitutionally permitted. Josephine and George returned to Boston after the Civil War began and lived on Cambridge Street in the West End. They had both achieved the prominence associated with certain forms of “respectability.” George Ruffin became the first black graduate from Harvard Law, and served in the state legislature; he stood out for being pro-suffrage, just like Josephine. She became president of the West End League of the Massachusetts Suffrage Association, and years later helped start Boston’s first chapter of the NAACP.[1] But their individual achievements were not the final word, especially for Josephine. From her home in Boston, she founded the first national publication by and for African-American women, The Woman’s Era.

During the tenure of The Woman’s Era, 1894 to 1897, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and her eloquent daughter, Florida Ruffin Ridley, intended for news and editorial content to build a bridge between African-American “women’s clubs.” Volunteer correspondents contributed information about African-American women’s clubs from numerous states and cities, including New York, Washington, Kansas City, New Bedford, Providence, and Boston. The Boston club was Ruffin’s own, also called The Woman’s Era, and it invited all women, black or white, to agitate for “the oppressed everywhere.”[2] The journal covered a variety of topics, such as women’s suffrage, the folly of deporting black people through “colonization,” tips for “domestic science,” and the problem of segregated white women’s organizations. But Ruffin’s editorials gave the strongest voice to organizing efforts against lynching. In the May 1894 issue, Ruffin wondered how the federal government could “go to war, spend millions of dollars and sacrifice thousands of lives” yet “cannot spend a cent to protect a loyal, native-born colored American murdered without provocation…in Alabama.”[3] Ruffin especially supported the anti-lynching activism of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, whose investigative reporting and data collection eviscerated the rationalizations of Southern elites and Northern moderates.[4] Ruffin had even written a critique of Frances Willard, president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, who initially chose not to oppose lynching in a gamble for Southern support.

To a large degree, The Woman’s Era was intended for middle-to-upper class black women. Ruffin herself called it a “high class paper” aimed at addressing the strictures on “educated, refined black women.”[5] This may appear as “respectability politics,” in contemporary terms, yet Ruffin understood that even wealthy, culturally sophisticated African-Americans would surely face overt, arbitrary prejudice. Ruffin once wrote an editorial against pervasive housing segregation in Boston, challenging white homeowners who told their realtors to never sell their properties to black people, regardless of ability to pay.[6] While Ruffin often wrote about Boston, the journal was sold primarily from homes in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C. Chicago, Denver, Kansas City (Missouri), New Orleans, and even New Brunswick, Canada. This wide reach of the paper, and its apparent ability to put black women’s clubs in conversation, made Woman’s Era the official newspaper of the “Black Woman’s Club Movement.”[7] The publication’s visibility allowed Ruffin and the Boston Woman’s Era Club the opportunity to call for a national convention of African-American women. For Ruffin, a national organization would build upon the emergent power of clubs all over, and that a “coming together” would provide “helpfulness, inspiration and broadening.”[8] In doing so, The Woman’s Era inspired the founding of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896, with Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin as its first vice president. The “power of the word,” so expressed by Ruffin’s publication, was a source of political, cultural, and moral advocacy by African-American women in Boston and the nation as a whole.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Rodger Streitmatter, “Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin: Driving Force in the Women’s Club Movement,” Raising Her Voice: African-American Women Journalists Who Changed History (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1994), 61-72; Karen Pastorello, “Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement: Revolutionary Reformers by Barbara F. Berenson (review),” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 50:1, Summer 2019, 136-137; Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and Florida Ruffin Ridley, “The Woman’s Era Club,” Woman’s Era 1:1, March 24, 1894, Emory Women Writers Resource Project; Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, “How to Stop Lynching,” The Woman’s Era 1:2, May 1, 1894, Emory Women Writers Resource Project; Patricia A. Schecter, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 108-109; Linda Steiner, Carolyn Kitch, and Brooke Kroeger, Front Pages, Front Lines: Media and the Fight for Women’s Suffrage (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2020); Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, “Editorial,” Woman’s Era 1:9, December 1894, Emory Women Writers Resource Project; Teresa Blue Holden, “A Presence and a Voice: Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and the Black Women’s Club Movement,” Bury My Heart in a Free Land: Black Women Intellectuals in Modern U.S. History (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2017); Francesca Sawaya, “Situated Expertise: Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Pauline Hopkins, and the NACW,” Modern Women, Modern Work: Domesticity, Professionalism, and American Writing, 1890-1950 (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, “Again the Convention,” The Woman’s Era 1:8, November 1894, Emory Women Writers Resource Project; Knight, S. (2007, January 19) George Lewis Ruffin (1834-1886). Retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/ruffin-george-lewis-1834a-1886/; Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. (2011). In Massachusetts Hall of Black Achievement. Item 32. Available at https://vc.bridgew.edu/hoba/32