Maria Stewart

One of the first American women of any race to give a public address in the nineteenth century, Stewart was one of Boston’s prominent Black abolitionists who lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill in the 1830s.

Maria Stewart (previously Maria Miller) was born free in Hartford, Connecticut in 1803. Her parents are unknown, but Stewart became an orphan at five years old. From five to fifteen, Stewart was the indentured servant of a minister. During that time she taught herself to read and write by sneaking books out of the minister’s library. At the end of her indenture, Stewart attended free “Sabbath schools” (Sunday schools) in Connecticut. Maria later moved to Boston and married James Stewart in 1826. James, a Black man, was a Naval veteran of the War of 1812 and a shipping agent. David Walker, a prominent abolitionist in Boston, befriended the Stewarts, and James Stewart might have transported copies of Walker’s Appeal to the South on his shipping routes. When the Walkers moved to Bridge Street, the Stewarts moved into the Walkers’ former home on 81 Joy Street, on the north slope of Beacon Hill.

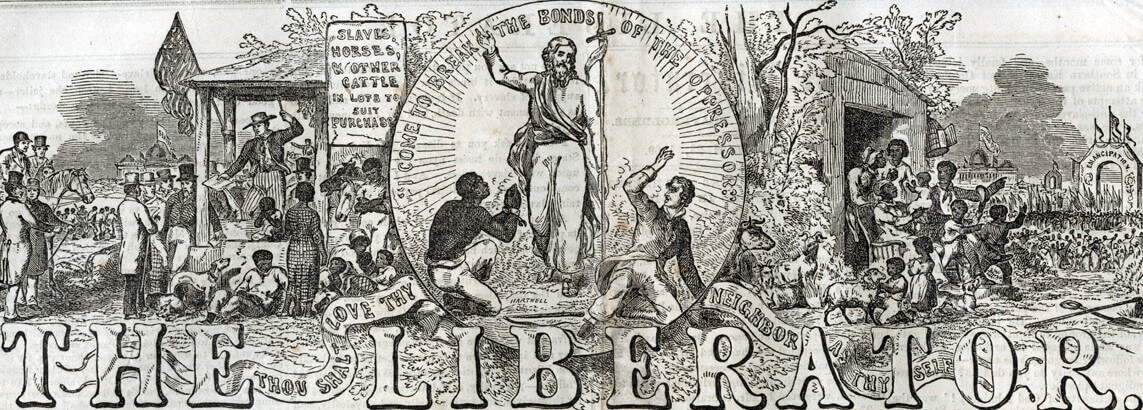

Maria Stewart became active in the abolitionist movement by joining the Massachusetts General Colored Association. She also regularly attended services at the African Baptist Church in Boston’s African Meeting House. James Stewart suddenly died in 1829, but the white executors of his will claimed Maria’s inheritance. Maria Stewart took the executors to court for two years, but she did not prevail and was left poor. Stewart since came into her own as an abolitionist inspired by her religious convictions. She impressed William Lloyd Garrison, who published many of Stewart’s writings in The Liberator during the 1830s. Two of her pamphlets, Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality in 1831 and Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart in 1832, were popular readings and culminated in a public speaking career. In April 1832, Stewart spoke to an audience entirely of women at the African American Female Intelligence Society founded in Boston. In September 1832, Stewart spoke to an audience including men at Franklin Hall, where the New England Anti-Slavery Society met. Stewart argued in the Franklin Hall address that the racism and exclusion faced by Black people in the North was comparable to the injustices of slavery in the South. Black Americans in both the North and South were condemned by the structures of society to lives of hard labor. Stewart believed strongly in the potentials of Black people stuck in these conditions, imploring the audience to “look at many of the most worthy and interesting of us doomed to spend our lives in gentlemen’s kitchens.” The speech appealed frequently to Stewart’s sense of religious inspiration and American identity.

Stewart’s next two public addresses in Boston were on February 27, 1833 at the African Masonic Hall on “African Rights and Liberty,” and her “Farewell Address” on September 21, 1833 before moving to New York. In the Farewell Address, Stewart responded to the backlash she received for being a woman engaged in public speaking, which contemporary observers believed improper. Audiences with both men and women were considered “promiscuous.” Stewart’s speech at Franklin Hall in 1832 was one of the first recorded cases of any American woman, Black or white, speaking to a public audience.

In 1834, Maria Stewart joined a “Female Literary Society” composed of Black women in New York. She became a teacher, later moving to Baltimore, MD and Washington, D.C. Stewart taught in D.C. during the Civil War, and in 1870 she remained in the District to direct housekeeping at the Freedmen’s Hospital and Asylum. This senior position was previously held by Sojourner Truth. In 1878, Stewart finally received a widow’s pension, of $8 a month, for James Stewart’s service in the War of 1812. With the pension she republished her Meditations with reflections on her experiences of the Civil War. Stewart died in the Freedmen’s Hospital on December 17, 1878.