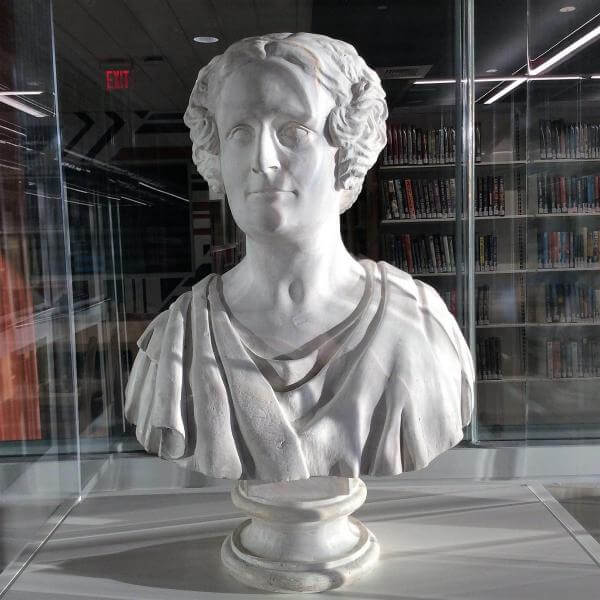

Maria Weston Chapman

The Boston-based anti-slavery activist, Maria Weston Chapman (1806-1885), was a leading voice in the abolitionist cause and an advocate for women’s participation. As both a dedicated abolitionist and family woman, “Captain” Chapman as she was known, pushed hard for what she believed in. As a founding member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, her voice was influential in the Boston area abolitionist movement.

Born in Weymouth to Warren and Nancy Bates Weston in 1806, Maria (pronounced ma-RYE-uh) Weston grew up on her family’s farm alongside her seven younger siblings. With the help of her uncle, Joshua Bates, she finished her formal education in London, an experience that many women of her age did not share. In 1828, she returned to Boston as principal of Ebenezer Bailey’s Young Ladies High School. The school was an attempt to advance public education for girls.

Two years later in 1830, she married Henry Grafton Chapman. Her husband was a merchant and abolitionist closely connected to William Lloyd Garrison. Mr. Chapman’s family business refused to do business involving slave labor. Through her husband, Chapman entered abolitionist circles. She developed a growing investment in the national movement as she joined Boston’s merchant-class society.

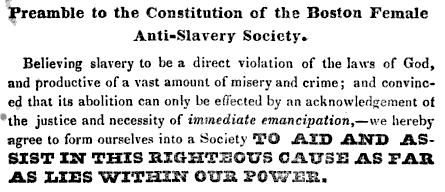

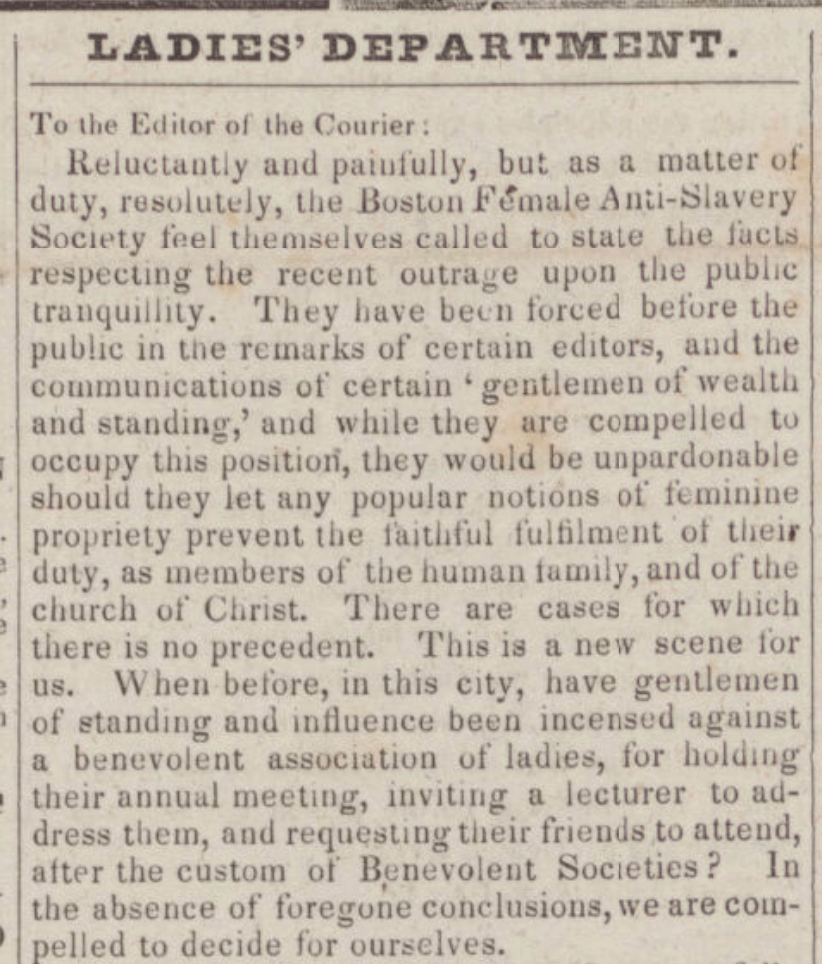

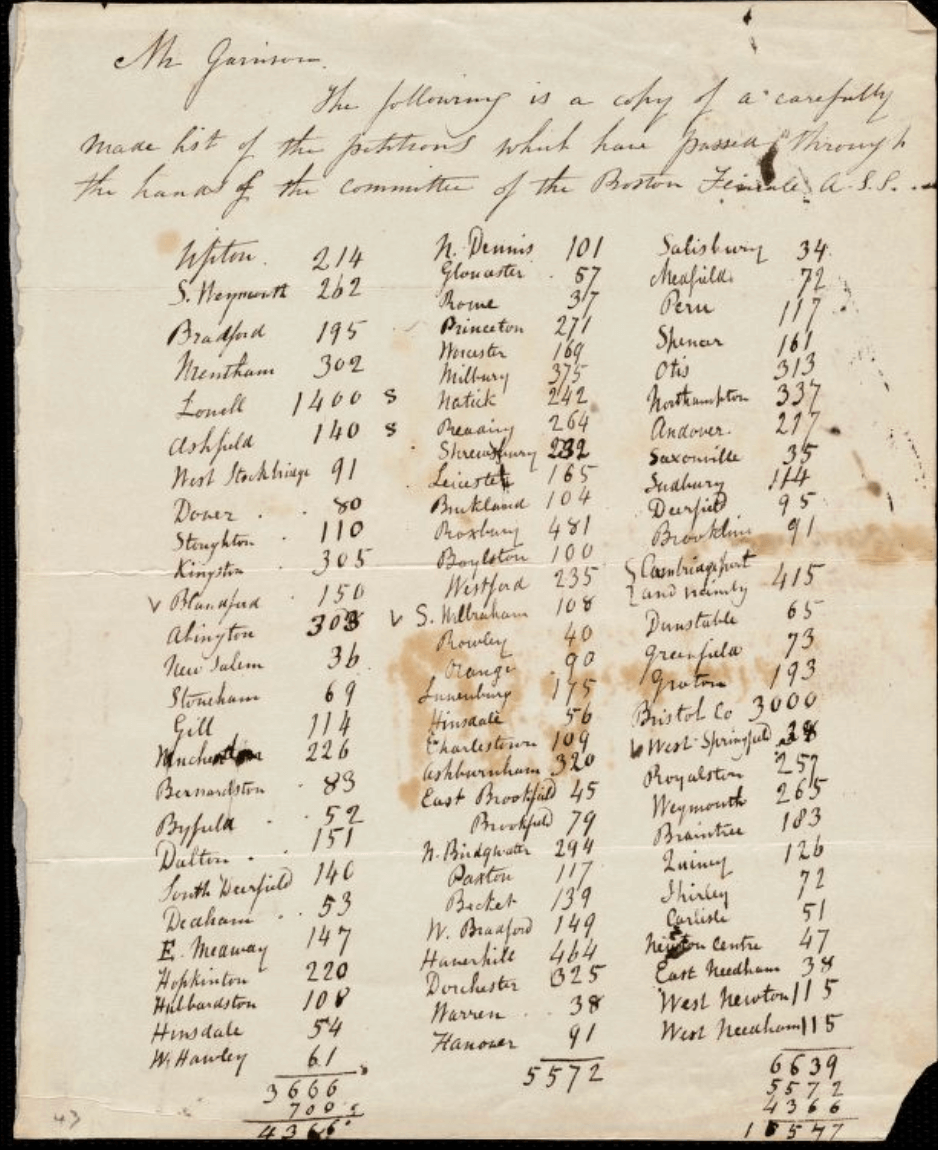

Newly married and newly committed to abolition, Chapman founded The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS) in 1834. Her co-founders included 12 other women, among them her sisters Caroline, Deborah, and Anne. With an established board, membership fees, scheduled meetings, and a constitution, the women organized themselves into a society. They believed “abolition can only be effected by an acknowledgement of the justice and necessity of immediate emancipation.” They vowed to “aid and assist in this righteous cause as far as lies within our power.” Anyone who aligned themselves with the mission and constitution could join for fifty cents a year (the equivalent of $18 today). The group included both Black and white members. The Black members included Eunice R. Davis, who was on the board, and Susan Paul, the author of the first biography of an African American published in the U.S. The BFASS was one of the leading abolitionist societies in Boston. They petitioned local and state governments, circulated anti-slavery newspapers, and held an annual bazaar. Chapman, as the group’s secretary, was one its most active and impassioned members.

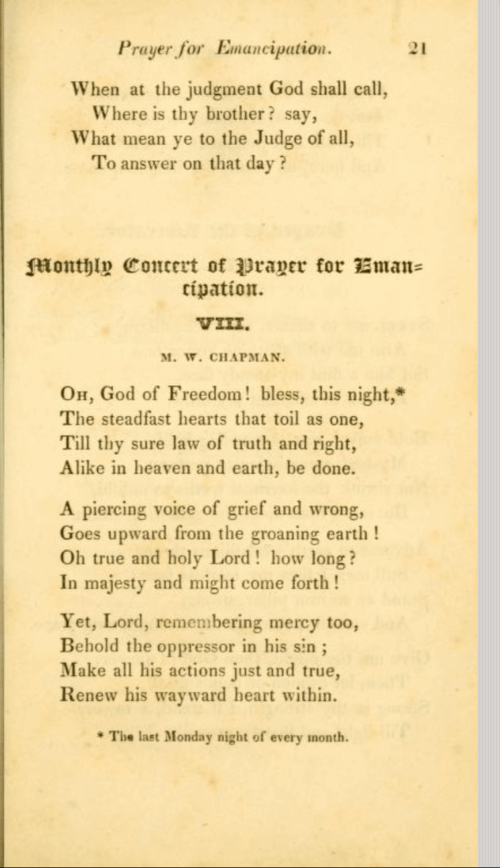

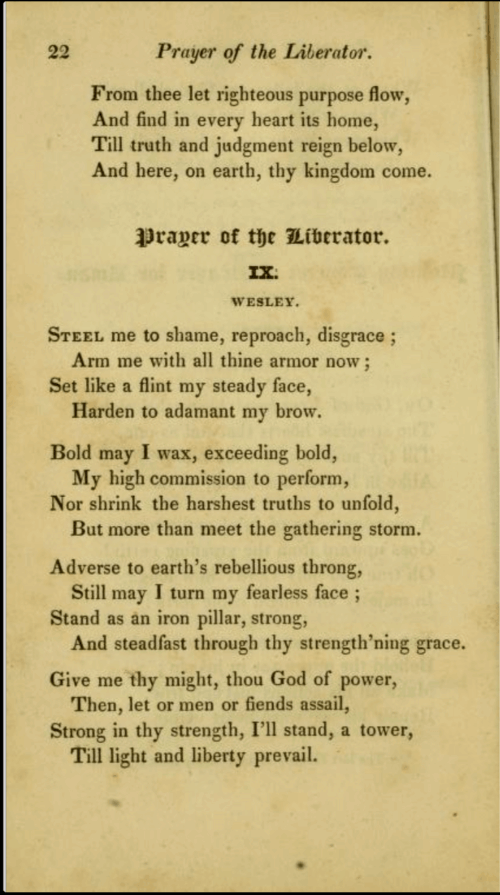

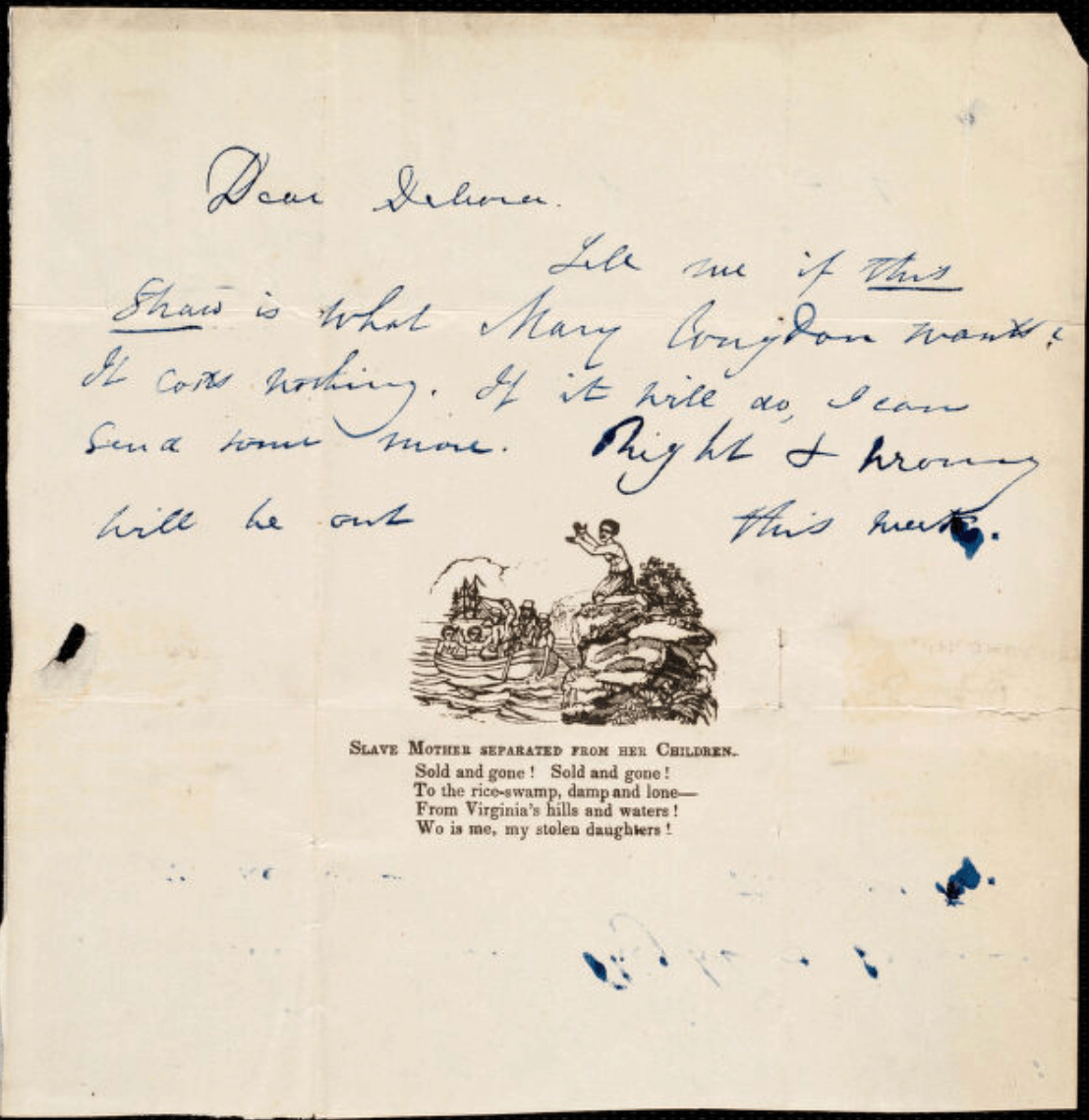

Alongside her efforts with the BFASS, Chapman engaged in anti-slavery outreach through the mass media of the time: newspapers. On several occasions, she assisted Garrison by editing The Liberator. This abolitionist newspaper circulated the writings of male, female, Black, and white writers. She edited and published over a dozen editions of The Liberty Bell, which was gifted or sold to those who attended the yearly Boston Anti-Slavery Bazaar. Chapman also contributed her editing skills to The National Anti-Slavery Standard. She published Songs of the Free and Hymns of Christian Freedom (1836), among the first anti-slavery songbooks published in the country. Her essay Right and Wrong in Massachusetts (1839) advocated against the exclusion of women in abolitionist societies. Chapman spent much of her career pushing for women’s inclusion in the cause.

On October 21, 1835, a growing mob of anti-abolitionist men formed outside the offices of The Liberator at 21 Cornhill Street (today underneath Government Center Plaza). On this night, Garrison was to speak at the meeting of The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society with 45 women in attendance. After an unsuccessful argument with the mob, Garrison had to flee. He eventually found himself at the Leverett Street Jail where he was kept for his own safety. Mayor Theodore Lyman attempted to quell the mob and cancelled the society’s meeting. Chapman was critical of the anti-abolitionist merchants. She declared they were “elbow deep in guilt and blood.” Fed up with the mayor and the mob, Chapman announced “if this is the last bulwark of freedom, we may as well die here as anywhere.” The society bravely left the building arm in arm, with each member of color linked to a white member. They walked to Chapman’s house at 11 West Street to finish the meeting.

The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society gained a voice in the fight against slavery. Their leader was undoubtedly Maria Weston Chapman and she became a well known abolitionist. In 1838, as Chapman spoke at the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in Philadelphia, a mob threw bricks at the window. The next day, the mob burned down the new Pennsylvania Hall where she had spoken. Abolition was not a popular position and there was risk, even for white women, who agitated against slavery.

Chapman was at the center of the “Boston Clique.” This was a term for influential white abolitionists who were vocal in many antislavery societies. The clique allowed women to partake in debates that were usually male-dominated and push the boundaries of the female sphere.

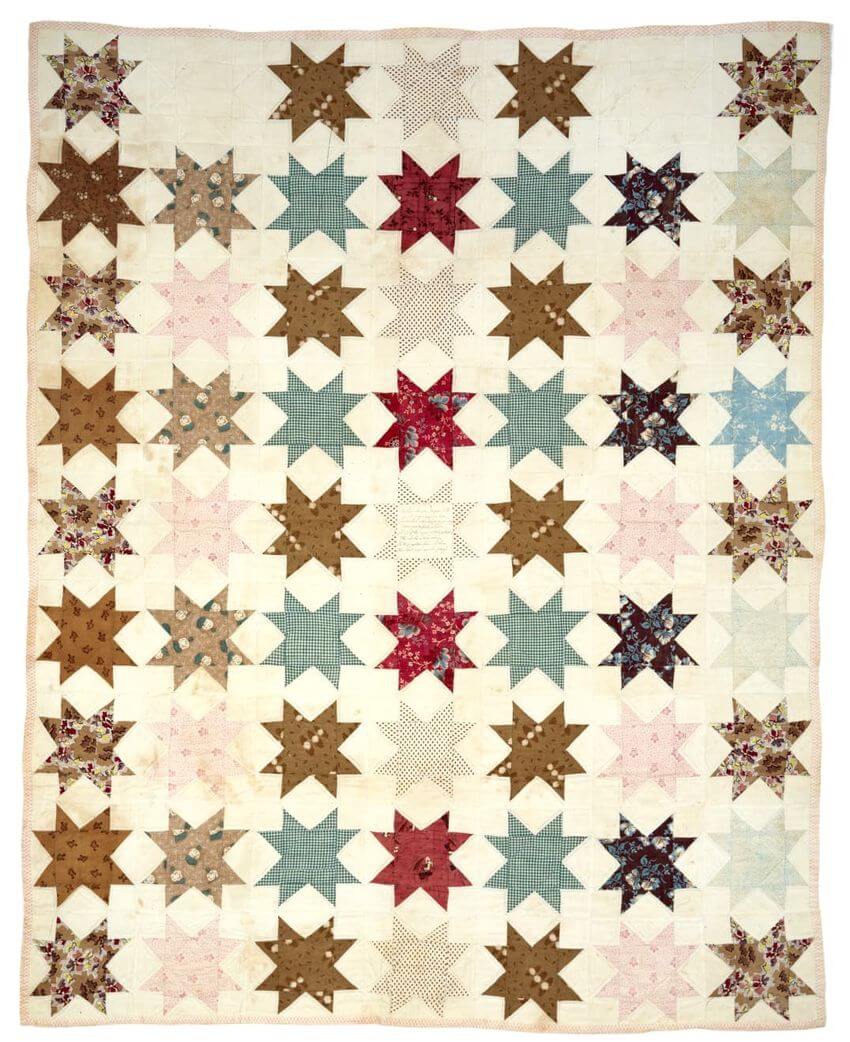

Through 1840, the BFASS circulated pamphlets, interviewed and published the writings of former slaves, petitioned local politicians, and held a fundraising anti-slavery bazaar every year around Christmas. At the bazaars or fairs, members sold their homemade clothing, needlework, and quilts. They raised money for their own society and the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. At the time, the state-wide society, where Chapman’s husband was treasurer, was all male. These bazaars encouraged consumers to spend their money supporting local merchants while fighting for a greater cause. Chapman and her husband lived in various locations in what is now downtown Boston, however, her in-laws had a home on Beacon Hill which hosted at least one bazaar.

The BFASS dissolved in 1840, much to Chapman’s dismay, due to internal schisms in the organization. “Captain” Chapman, as she was nicknamed, re-formed the society and continued to focus on the yearly bazaars and continued publishing The Liberty Bell.

Chapman lost her youngest daughter in 1841 and her husband in 1842 to tuberculosis and threw herself into abolition work. In 1848, Chapman traveled with her family to live in Paris to further her children’s education in Europe as she had done. Over seven years in Paris, Chapman attended the Paris Peace Conference, the London Conference, collected items for the bazaars, and added European writers to The Liberty Bell. She and her sisters created an outpost of the American anti-slavery effort abroad.

In her final years dedicated to the cause, Chapman began supporting the Republican party in their anti-slavery efforts. She even was in favor of war to end slavery when the Civil War broke out. This was a change from her earlier work dedicated to moral suasion, or the idea that anti-slavery activists could convince Americans of slavery’s evils.

In 1863, once Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, Chapman retired from her activism and from public life. Chapman was proud of the work she put into the cause and celebrated its victory. She lived the rest of her life in her hometown of Weymouth where she died of heart disease at 78 years old in 1885. Upon her death, the Boston Globe’s obituary called her a “noted woman” and praised her dedication to the cause. She saw, the obituary noted, “with intense satisfaction, the last vestige of slavery destroyed” and was able to live her remaining years in quiet. An ironic twist from her early years when she never allowed herself nor her cause to be silenced.

Chapman was not only a firebrand organizer and writer for the anti-slavery cause, but also someone who worked to ensure women, both Black and white, were not left out of the cause of abolition.

Article by Catherine Stowe, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: American Abolitionists and Antislavery Activists: Conscience of the Nation, “Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS)” April 4, 2021; The Boston Globe, “Death of a Noted Woman: Mrs. Henry Grafton Chapman, Wife of the Treasurer of the Anti-Slavery Society, Passes Away” (July 14, 1885); John K. Hastings “Anti-Slavery Landmarks in Boston,” (Boston Evening Transcript, September 1, 1897); Maggie, “Maria Weston Chapman: Author and One of the First Female Abolitionists”, (History of American Women, blog, November 24, 2012); National Parks Service, “The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society”, July 15, 2024 | “Defining Their Sphere: Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society” | “Maria Weston Chapman” July 12, 2024 | “Site of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society Office,” January 8, 2023; Kim Reynolds, “Notable Women, Notable Manuscripts: Maria Weston Chapman,” (Boston Public Library, March 1, 2022); Heather Rockwood, “International Women’s Day 2021: Meet Maria Weston Chapman,” (The Beehive, Massachusetts Historical Society, March 15, 2021); Adam Tomasi, “William Lloyd Garrison,” (The West End Museum, November 11, 2021); Town of Weymouth “Maria Weston Chapman by Edmonia Lewis”.