Nancy Gardner Prince

Nancy Gardner Prince’s world travel and experiences were unique for a 19th century Black woman, yet she still suffered from many of the harsh trials facing her people.

Nancy Gardner Prince was born in 1799 in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Her father, Thomas Gardner was a Nantucket whaler who owned land in the New Guinea neighborhood of Nantucket. Her mother, Mary Wornton, met and married Thomas in 1790. The Gardner’s were part of the small, free Black population of about 6,500 living in Massachusetts at the time. Nancy’s father died of tuberculosis the year she was born; her mother later remarried another mariner and the family moved to his home in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Tragically, Nancy’s stepfather was taken prisoner by the British during the War of 1812 and died in captivity.

Nancy spent much of her childhood caring for her mother and seven siblings, and helped support the family by doing seasonal work on local farms. When she was fourteen, she and her sister Sylvia moved to Salem to work as domestics. A year later, Sylvia left her abusive employers in search of better work in Boston. When Nancy learned that her sister had been forced to work in a brothel, she walked twenty five miles from Salem to Boston and successfully wrestled Sylvia away from the owner of the brothel. The sisters remained in Boston, found a home on the north slope of Beacon Hill, and Nancy learned the trade of needlework. These early years marked with hardship were most likely what inspired Nancy to seek solace in religion. A few years after settling in Boston, she was baptized by prominent minister and abolitionist Rev. Thomas Paul at the African Meeting House. She became an active member of the church, dedicating her life to religious teachings and humanitarian work.

In 1823 Nancy met Nero Prince, a prominent Prince Hall Freemason who had earned a position in the court of Russian Czar Alexander I. Most of what we know about Nero comes from Nancy’s writing.

Mr. Prince was born in Marlborough, and lived in families in this city. In 1810 he went to Gloucester, and sailed with Captain Theodore Stanwood for Russia; he returned with him, and remained in his family, and at this time visited my mother’s family. He again sailed with him, in 1812, for the last time. Captain Stanwood took with him his son Theodore, for the purpose of attending school in the city of St. Petersburg. Mr. Prince went to serve Princess Purtossozof, one of the noble ladies of Court. It is well known that the color of one’s skin does not prohibit from any place or station that he or she may be capable of occupying.

Nancy and Nero wed and moved together to Russia in 1824.

Rulers of the Russian Empire had adopted a tradition of maintaining a contingent of what were known as Russian Moors in their courts. Nancy observed that “the number of colored men that filled this station was twenty; when one dies, the number is immediately made up. Mr. Prince filled the place of one that had died.” Nancy described in detail the Prince’s arrival at court:

We passed through the beautiful hall, a door was opened by two colored men, in official dress, and there stood the Emperor Alexander on his throne, in royal apparel. The throne is circular, elevated two steps from the floor, and covered with scarlet velvet tasseled with gold. As I entered, the Emperor stepped forward with great politeness and condescension, and welcomed and asked me several questions; he then accompanied us to the Empress Elizabeth; she stood in her dignity, and received me in the same manner. They presented me with a gold watch, and fifty dollars in gold.

While in St. Petersburg Nancy started a business making and selling children’s clothing, and also earned income by boarding children, which led to her establishing an orphan’s home in St. Petersburg.

After almost ten years in Russia, Nancy returned to Boston in 1833 due to ill health. Nero had planned to follow her, but sadly died in Russia before departing. Once Nancy’s health improved, she established a society for orphans in Boston and became a founding member of William Lloyd Garrison’s New England Non-Resistance Society and a member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society.

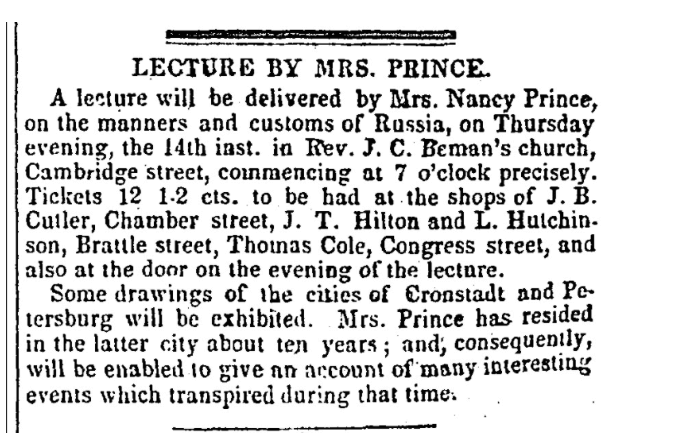

Nancy also began traveling again for a short time. In 1839, she held a series of lectures on Russian culture at the Abiel Smith School and the AME Zion Church. During one of her lectures she met a minister from recently emancipated Jamaica who encouraged her to travel to his country with a missionary group so she “might aid, in some small degree, to raise up and encourage the emancipated inhabitants, and teach the young children to read and work … and put their trust in the Saviour.” Upon returning from her last trip there, she endured a harrowing experience when her ship had to dock temporarily in New Orleans. As white passengers on her ship disembarked, Nancy remained onboard for fear of being enslaved, a danger Black people faced in southern ports. She finally convinced officials of her free status and was allowed to continue north, but not before suffering harassment by crew members and having her luggage looted.

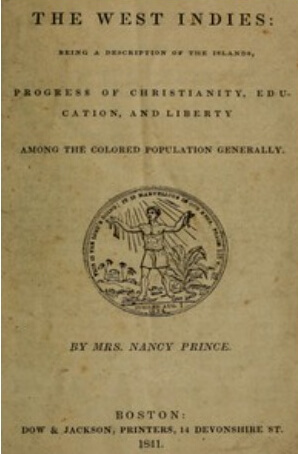

After returning to Boston, she published a pamphlet entitled The West Indies: Being a Description of the Islands, Progress of Christianity, Education, and Liberty Among the Colored Population Generally (1841). Nancy also focused her energies on the abolitionist movement and strengthening her community. In 1847 a group of children reported to Nancy that a slave catcher named Woodfork was at the Smith Court home of Mrs. Dorsey, a neighbor known to have escaped from enslavement. Nancy gathered a group of women and went to Mrs. Dorsey’s rescue. As recounted in an 1894 issue of The Women’s Era newspaper, “only for an instant did the fiery eyes of Mrs. Prince rest upon the form of the villain…for the next moment she had grappled with him, and, before he could fully realize his position she, with the assistance of the colored women that had accompanied her, had dragged him to the door and thrust him out of the house.” Woodfork left Boston without Mrs. Dorsey.

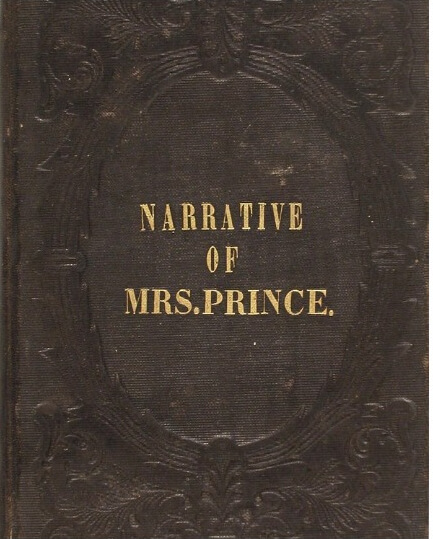

In her remaining years, while struggling with ill health, Nancy spoke at the 1854 Women’s Rights Convention in Philadelphia, and supported herself by writing a book, A Narrative of the Life and Travels of Mrs. Nancy Prince Written by Herself. The work was published three times between 1850 and 1856. It is significant as a rare travelog of a Black woman in the nineteenth century, and by Nancy’s eyewitness accounts of historical events in Russia and the West Indies: a devastating flood, cholera epidemic, life in a newly emancipated country, and the political upheaval of the St. Petersburg riots after the unexpected death of Alexander I in 1826. In the preface to the 1856 edition of her book she mentioned losing power in both of her arms, and she died three years later in 1859 in Boston at the age of sixty.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources:Foster, Frances Smith. Written By Herself: Literary Production By African American Women, 1746-1892. Indiana University Press, 1993.; Museum of African American History, Boston: National Parks Service; Nantucket Historical Association; Prince, Nancy. A Narrative of the Life and Travels of Mrs. Nancy Prince Written by Herself. Published by the author. Boston, MA, 1850; Project Gutenberg; Schriber, Mary Suzanne. Telling Travels: Selected Writings by Nineteenth-century American Women Abroad.Northern Illinois University Press, 1995; Scott, J. H. (2017) Travel as Subversion in 19th Century Black Women’s Narratives. Advances in Literary Study, 5, 105-121; The Woman’s Era 1, no. 5 (August 1894); https://womansera.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Vol_I_No_05.pdf; Waters, Kristin, and Carol B. Conaway, editors. Black Women’s Intellectual Traditions: Speaking Their Minds. University Press of New England, 2007