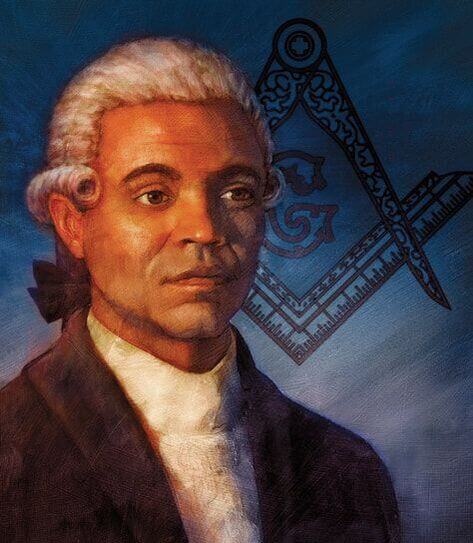

Prince Hall

Prince Hall was a leader in Boston’s free black community on the North Slope and Copp’s Hill. He was one of the United States’ most vocal early abolitionist voices and a founder of Prince Hall Freemasonry. Hall advocated for black education and equality, running a school and making a wide array of arguments in service of bringing the fundamental promises of the Revolution to all Americans.

Prince Hall was born in 1735 in Bridgetown, Barbados (then part of the British West Indies) to a free Black woman of French and African descent and a white English leatherworker. Little is known about his early life, such as whether Hall once worked as an indentured servant. But Hall became a prominent member of Boston’s Black community by the 1770s. A member of the Congregational Church and in his second marriage by 1773, Hall worked in Boston as a peddler, caterer, and leatherworker. He owned his own home and leatherworking shop, and in 1777 he made five drumheads for a Boston artillery regiment.

During the Revolutionary War, Hall encouraged enslaved persons to serve with the Continental Army, believing that if African Americans were involved in the creation of the new nation they would gain freedom within it. While African Americans were initially denied entry into the colonial service, they (including Hall) were eventually allowed in after the British forces began to enlist them. After the war, Hall became the principle representative of Boston’s free Black community. He began writing equal rights legislation with other members of the community, but turned to community development, Masonry, and education after that legislation failed.

Hall joined the Boston’s Irish Constitution Freemasons in 1775 along with 14 other black men, forming an all-black lodge and becoming Grand Master. However, Hall and his fellow black Masons were marginalized within the brotherhood, and eventually broke off with the permission of London’s Grand Hall Number 55 to become the first independent African Lodge in 1784. In 1787, Hall wrote a letter to Governor James Bowdoin, requesting that the governor allow him to bring seven-hundred African Americans to answer a “call to arms” against Shays’ Rebellion in Springfield. Seven years later, in 1791, black Masons from across the country met in Boston to form the African Grand Lodge of North America, of which Hall became Grand Master.

During Hall’s time in the Masons he developed a uniquely black form of Freemasonry, and became a committed community activist. During the winters, the African Masons provided free firewood and ran food drives for the impoverished. Masons could also receive weekly “sick dues” when they were unemployed, funded by the monthly dues of members. On June 24, 1797, Hall gave an address to the African Lodge against the twin problems of the “iron yoke of slavery” nationwide, and the “daily insults in the streets of Boston” hurled by whites against Black Bostonians. Speaking to the daily threats that Black people experienced in the city, Hall concluded that “we may truly be said to carry our lives in our hands, and the arrows of death are flying about our heads.” In a time when white animosity seemed unavoidable, Hall lent support to the “Back to Africa” movement, lobbying the State Senate for funds to allow voluntary emigration to Africa, though he eventually abandoned the effort.

Hall spent the remainder of his life advocating for African Americans on the state and national levels. He pushed for higher quality education for Black children, petitioning in 1787 and 1800 for a separate Black public school in Boston when Black students experienced racism in majority-white public schools. When the state did not provide funding for a separate public school, Hall and others founded the African Free School in 1798, initially holding classes in the basement of Primus Hall’s home (Prince Hall’s son). In 1806, the African School moved its classes to the African Meeting House. Though Prince Hall believed in his time that a separate school met a communal need, the subsequent generation of Black Bostonians, such as William Cooper Nell, organized to end school segregation and discourage enrollment at the all-Black Abiel Smith School (founded in 1835) because of how racial classification limited Black students’ opportunities for an equal and adequate education.

Hall died in 1807 and was buried in Copp’s Hill Burying Ground in the Masonic tradition. Less than a year after his passing he was honored by the Masons, and the Grand Lodge he was instrumental in founding was renamed the Prince Hall Masons (also known as the Prince Hall Lodge). The Prince Hall Masons were the most influential Black fraternal organization in nineteenth-century Boston. Despite the Prince Hall Masons’ dedicated efforts in Boston’s Black community, the Grand Masonic Lodge of Massachusetts did not officially recognize the chapter until after the Civil War. Today there are more than 300,000 Prince Hall Masons in North America and Liberia, spread across some 4,500 lodges.

Article by Sebastian Belfanti and Adam Tomasi

Source: Find a Grave; History is Fun; James O. Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1979); Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Berlin, 1998)