Ray Reddick’s African-American Ancestors in Boston’s Historic West End

Raymond Reddick, a lifelong Boston resident who is now 74 years old, has spent decades collecting, documenting, and speaking to different audiences about his extensive African-American family history with deep ties to the historic West End. After his grandmother, Ruthena Felton King Reddick, passed away in 1985, Ray began his ongoing genealogical research, which started with stories from family members and countless boxes of family artifacts in his possession. Ray Reddick approached The West End Museum to collaborate on a project that highlights his nineteenth-century ancestors — West Enders and Black Bostonians — captivating lives. Northeastern University’s Reckonings project has collaborated with Reddick and The West End Museum to produce, after a series of oral history interviews, a two-part, co-created report that spotlights Ray Reddick’s family history.

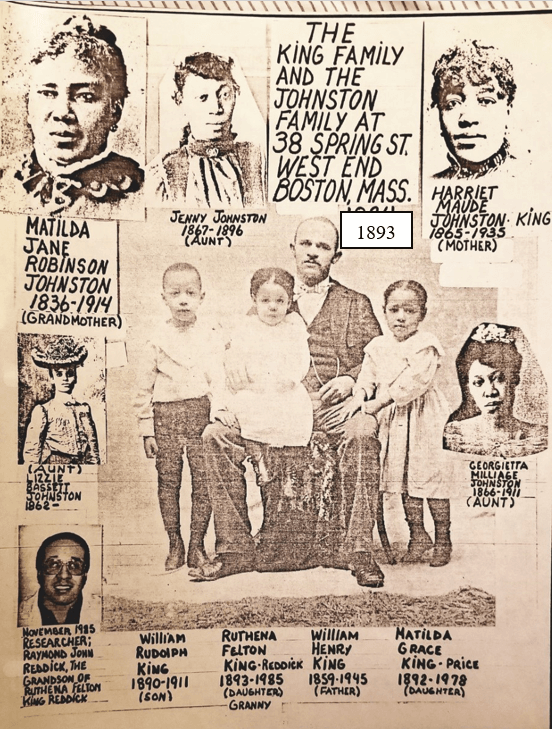

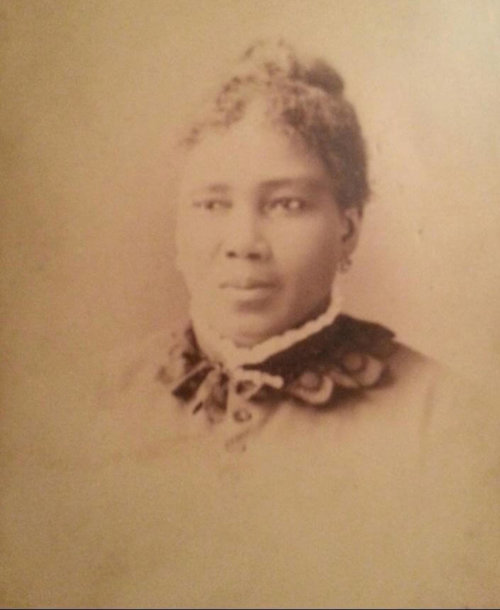

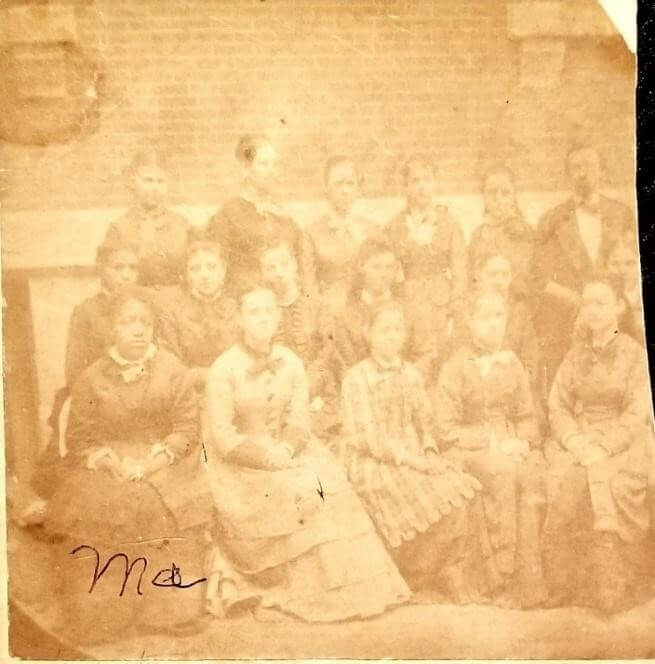

When Ray Reddick began collecting and documenting his family history in 1985, he produced the collage of family photographs below. Reddick’s photograph from November 1985 is in the bottom left corner. The captions for each photograph, in Ray’s handwriting, identify members of two branches on the Reddick family tree: the King and Johnston families that lived in the historic West End in the nineteenth century.

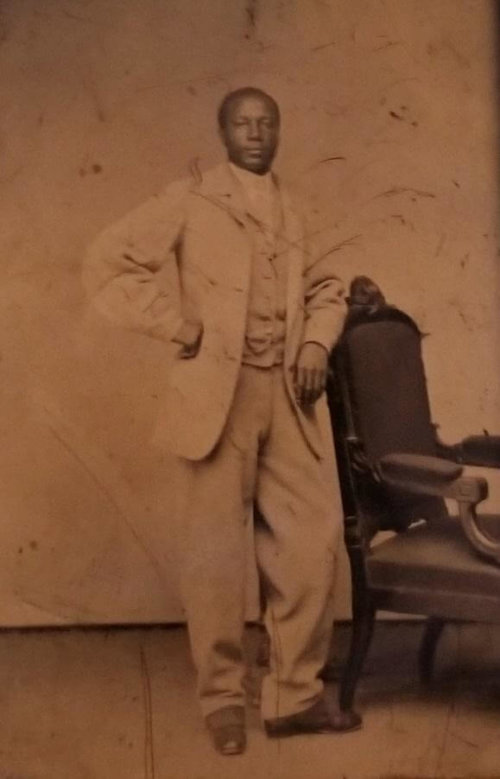

Ray Reddick’s great-great grandparents, James F. Johnston and Matilda Jane Robinson Johnston, were born in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia in 1829 and 1836, respectively. James Johnston’s parents were Daniel Johnston, from Norfolk, Virginia, and a woman named Hannah; Hannah was most likely an enslaved person because she did not have a surname (as far as early records could indicate). Matilda Jane Robinson’s parents, Isabella Gordon and Richard Robinson, were born in Leeds, England and moved to Virginia, then Canada. The Robinsons in Annapolis Royal lived amongst the Mi’kmaq, one of the Algonquian peoples in northeast North America and the original residents of the land. At this time, Annapolis Royal was a British colony occupied by thousands of Black Loyalists who left the United States in 1783, at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. Black Loyalists were enslaved people who supported the British during the Revolutionary War in exchange for their freedom. The Johnstons and Robinsons may have emigrated from the United States to Nova Scotia because they were Black Loyalists.

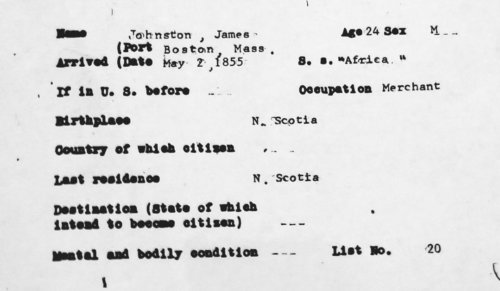

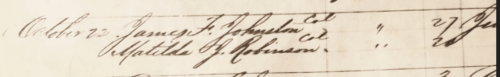

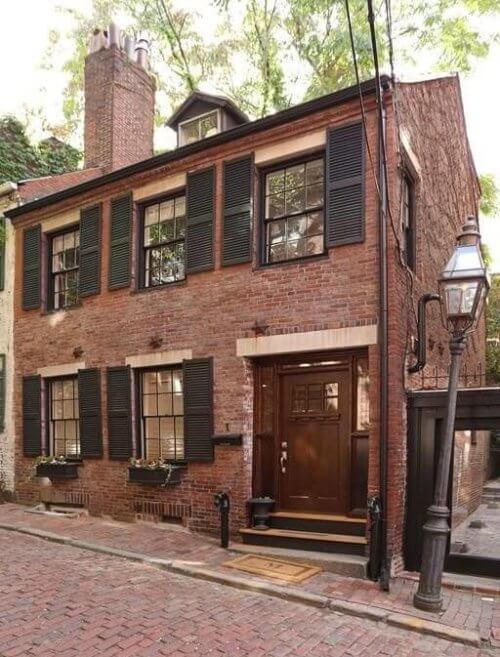

On May 2, 1855, James Johnston arrived at the port of Boston from Nova Scotia on the S.S. Africa. His occupation was “merchant” in the passenger log, and Johnston worked as a jeweler upon residing in Boston. James Johnston and Matilda Jane Robinson, a domestic worker, married on October 22, 1856 at the Twelfth Baptist Church, then on Joy St. in the historic West End. The service was presided over by Reverend Leonard Grimes, the Black minister and abolitionist who helped enslaved people reach freedom as a “conductor” for the Underground Railroad. In 1856, James and Matilda resided at 8 Sears Place in the historic West End. In 1858 they moved to 38 Spring Street in the West End. As their family grew, Matilda Jane Robinson Johnston became the family’s matriarch, as much of the extended family visited or stayed at her home on 38 Spring St. One of Matilda’s younger siblings, Frederick Arthur Robinson (born August 1852 in Annapolis Royal), moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1870 and became Cambridge’s first Black police officer in April 1884.

In 1860, more than 60 percent of Black Bostonians (1,395 out of 2,261) lived in the West End, particularly on the north slope of Beacon Hill (part of the historic West End). Many of these residents belonged to Boston’s nineteenth-century Black elite, whom sociologist Adelaide Cromwell called “the other Brahmins.” The Black upper class in the West End grew from successful businesses and intermarriage, both of which were made possible by “five generations of freedom” in the city that became a hub of organizing for the abolition of slavery and an end to racial discrimination in the public schools. James and Matilda Johnston belonged to the Black upper class; when their daughter, Harriet Maude King, passed away in 1935, the Boston Globe called her “the last of an old Bostonian aristocratic West End family.”

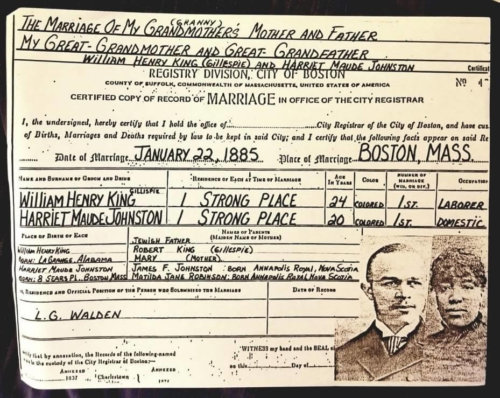

Harriet Maude Johnston was born in 1865 to James and Matilda Johnston in the West End. Hattie, as her family called her, was a domestic worker when she married William Henry King, a porter from Alabama, on January 22, 1885. Johnston and King resided at 1 Strong Place, at the foot of the north slope, when they were married. Hattie was a “loyal interested member” of multiple societies in Cambridge and Roxbury, particularly the William H. Carney Circle, an auxiliary of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic. The Grand Army of the Republic was a multiracial organization of Union Army veterans. The “Circle” Hattie belonged to was named for Sergeant William Carney, a Medal of Honor recipient, who served in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War; Carney is known for ensuring, as Union forces retreated from the raid on Fort Wagner, that the U.S. flag never touched the ground. In July 1921, the Grand Army of the Republic Hall on 46 Joy St. held an observance of the 56th anniversary of the 54th Regiment’s charge on Fort Wagner, and the celebration was assisted by “Sergt William H. Carney Circle, No. 37, Ladies of the G.A.R.”

Harriet Maude Johnston King died on February 8, 1935, though she had just before celebrated her fiftieth anniversary of marriage to William H. King while confined to her bed with ill health. Her funeral was held at St. Mark’s Congregational Church in Roxbury. The Globe noted that “a large number of friends attended the services to pay their silent tribute to one whom they never saw frown, nor from whose lips ever heard an unkind word.” Harriet and William had three children together; their son, William Rudolph King, passed away in 1911, and their two daughters, Matilda Grace King and Ruthena Felton King, were still alive when their mother died.

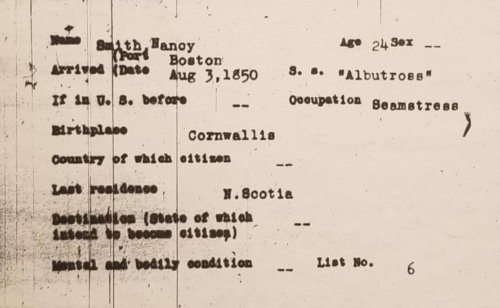

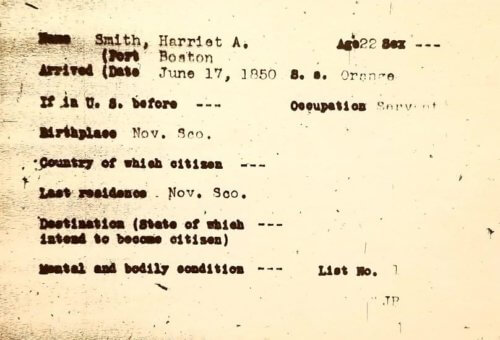

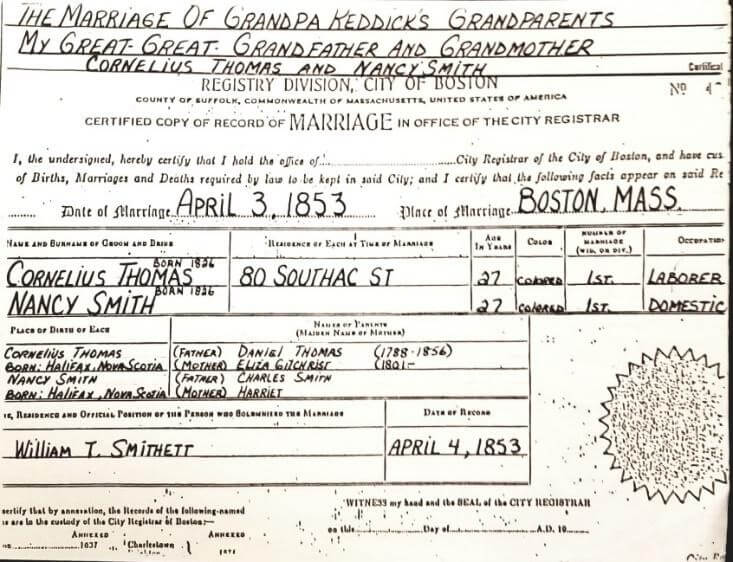

Another branch of Ray Reddick’s family tree, coming from the Thomas family, has a similar history beginning in Nova Scotia and ending up in the West End. Ray’s great-great grandfather, Cornelius Thomas, and great-great grandmother, Nancy Smith, were each born in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1826. Cornelius Thomas’s father, Daniel Thomas, freed himself from slavery in Norfolk, Virginia by escaping to Nova Scotia in 1812. Cornelius Thomas worked as a waiter and a carriage driver (earning $8 a month in the latter job) in Nova Scotia. He immigrated to Boston to seek greater economic opportunities, and became a naturalized United States citizen in 1844. He soon worked as a waiter for Peter Scratcher’s high-end boarding house on 40 Mt. Vernon Street, on the south slope of Beacon Hill. In 1850, Thomas became a “canvasser” for the Daily Chronotype newspaper; Thomas purchased the rights to multiple newspaper routes in Boston, selling many different local papers street by street. That year, Nancy Smith, a seamstress, left Nova Scotia for Boston. On August 3, 1850, Smith arrived at the port of Boston on the S.S. Albatross. Her sister Harriet Smith, a domestic worker, immigrated to Boston the month prior, arriving on June 17, 1850 as a passenger of the S.S. Orange.

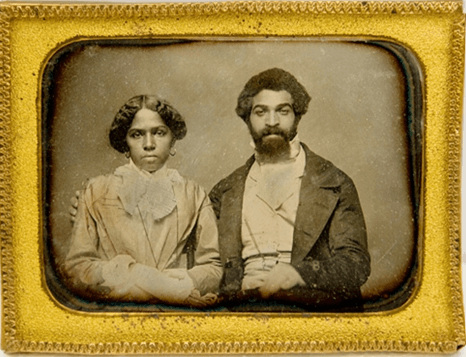

Nancy Smith and Cornelius Thomas met each other shortly after they took similar paths to Boston, and they married on April 3, 1853. The marriage certificate indicated that Cornelius and Nancy lived at 80 Southac Street (later Phillips Street) on the north slope of Beacon Hill in the historic West End.

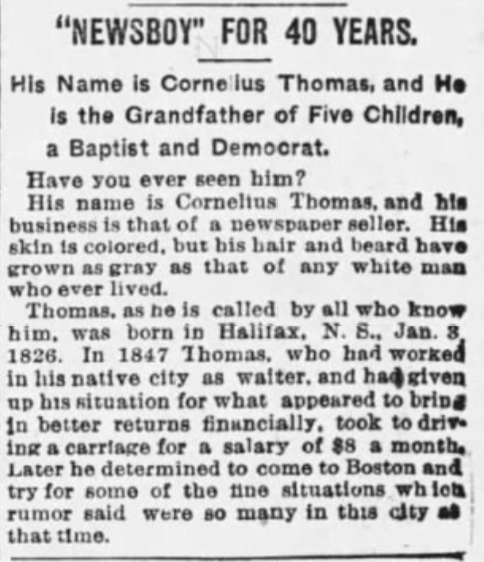

Cornelius Thomas had great success as a “news dealer.” He had been selling 1,000 papers a day just before the Civil War began, and was one of the first people to sell and deliver the first issue of the Boston Globe. Thomas sold newspapers over the next forty years, and his achievements inspired a profile by the Globe on April 8, 1893. By this time Cornelius and Nancy Thomas were living on Anderson Street, also on the north slope. The Globe described Thomas as “the Grandfather of Five Children, a Baptist and Democrat,” and commented on his racial identity: “His skin is colored, but his hair and beard have grown as gray as that of any white man who ever lived.” Thomas still worked from 5 AM to 6 PM each day, though he took on fewer routes on account of his old age.

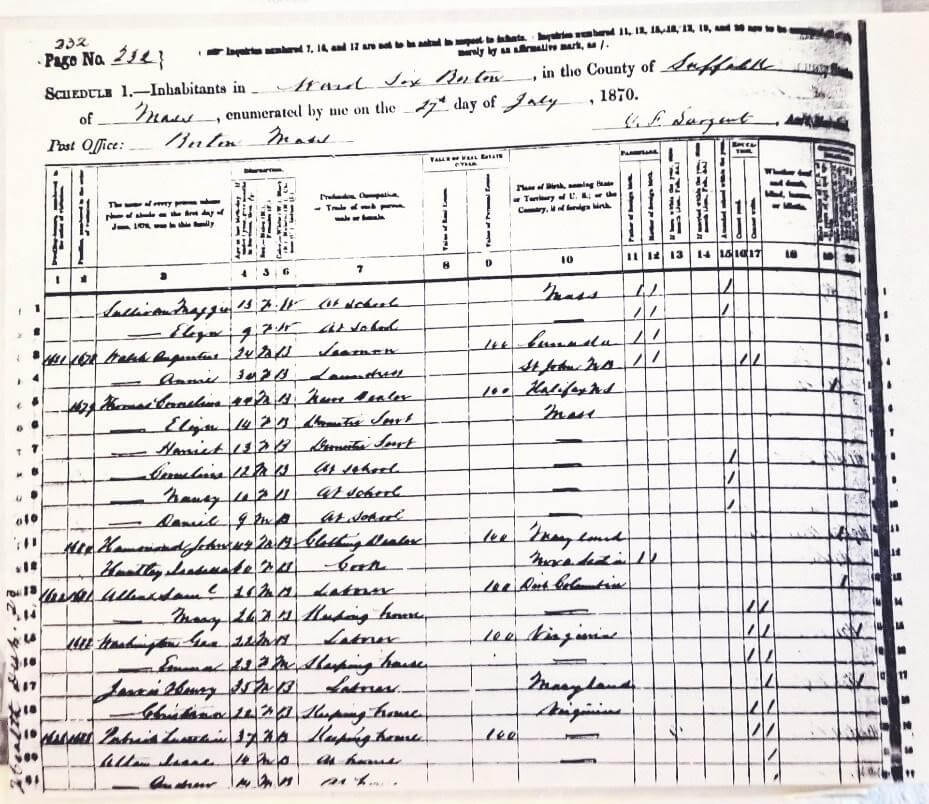

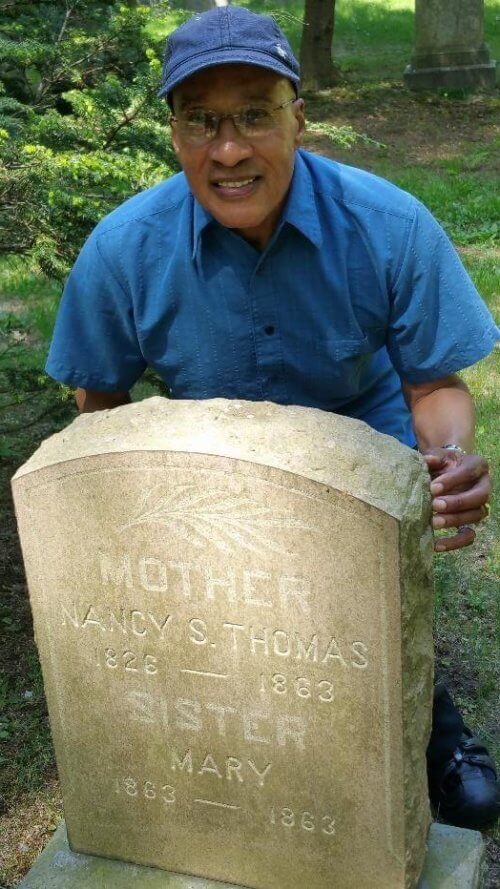

According to the 1870 census for Suffolk County, Cornelius and Nancy Thomas had five children: Eliza (14 years old in 1870), Harriet (13), Cornelius (12), Nancy (10), and Daniel (9). Eliza and Harriet were taken out of school to work as domestic servants and help raise the youngest three children, who were all in school. The youngest, Daniel, was born in 1861; Nancy Smith Thomas passed away in 1863.

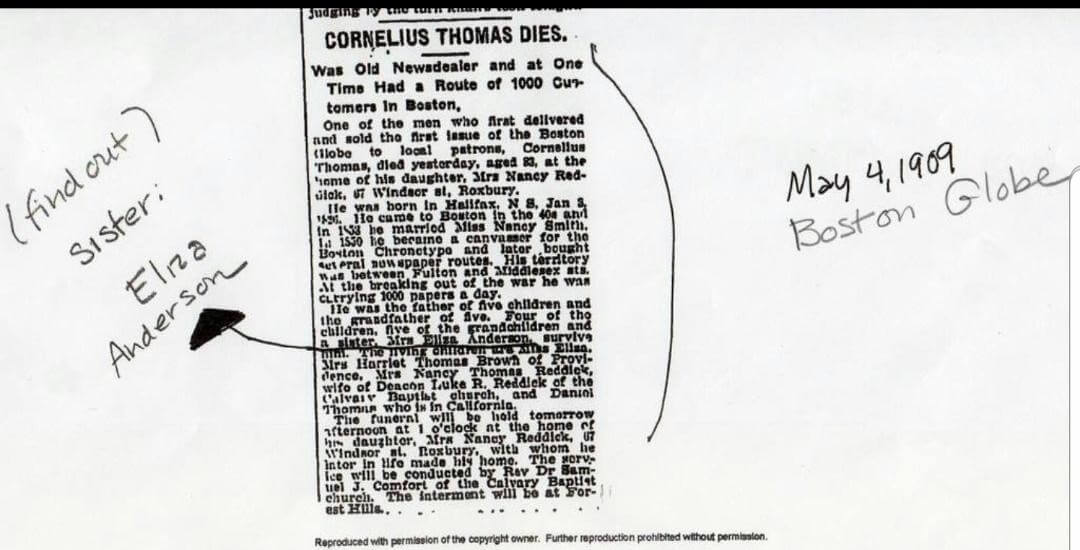

Cornelius Thomas died in 1909 at the age of 83. He passed away at the home of his daughter, Nancy Thomas Reddick, at 67 Windsor Street in Roxbury. Cornelius’s obituary noted that his daughter’s Roxbury address was where “he later in life made his home.” The service was held at the Calvary Baptist Church on Shawmut Avenue in the South End; Luke Reddick (1852-1921) served as Deacon of that church. Born an enslaved person in Rosedale, North Carolina, Luke later married Nancy T. Reddick. Luke Reddick owned four to five houses on Beacon Hill, and as a Deacon he founded the People’s Baptist Church on Camden Street in the South End. The church has a stained glass window dedicated in his honor. When Black Bostonians moved from the north slope of Beacon Hill to the South End at the turn of the twentieth century, Luke Reddick became the deacon for the congregation that left the African Meeting House on Beacon Hill.

The King and Thomas families came together when, on April 29, 1913, Ruthena Felton King (1893-1985; the daughter of William H. King and Harriet Maude Johnston) married Cornelius Thomas Reddick (1882-1972; the son of Nancy Thomas Reddick, 1859-1948, and Luke Rodgers Reddick, 1852-1921). Cornelius T. Reddick attended the People’s Baptist Church in the South End, as did all of he and Ruthena’s children over time. They lived at 67 Windsor Street in Roxbury, the address where Cornelius T. Reddick’s grandfather previously resided.

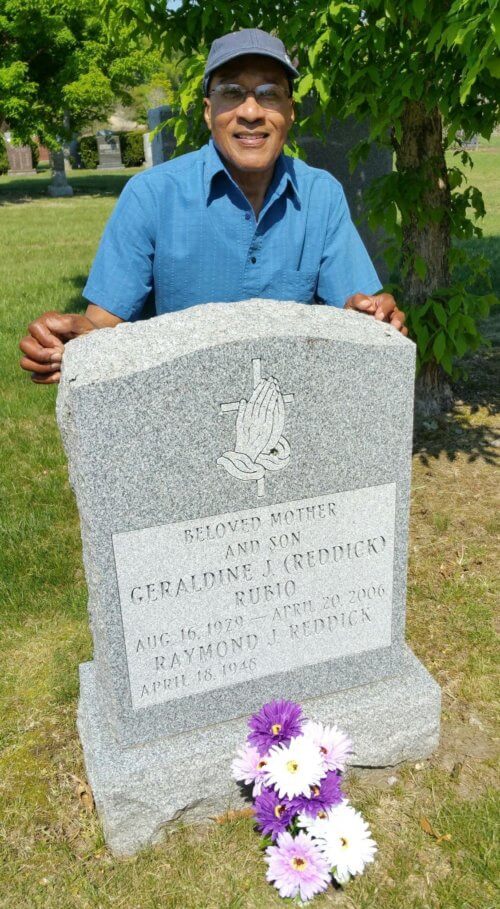

Many names were passed down over generations of the Reddick family, as the reappearance of names like Nancy, William, Cornelius, and Matilda demonstrates. Ruthena’s siblings were William Randolph King (born 1890), Matilda Grace King (born 1892), Zulee Felton King (born 1885, but passed away soon after birth), Bernice Mary King (born 1895), and James Gordon King (1900-1917). Geraldine Johnston Reddick Rubio (1929-2006), Ray’s mother, was the daughter of Ruthena Felton King Reddick and Cornelius Thomas Reddick. Ray Reddick was born on April 18, 1948, pictured below at his mother Geraldine’s headstone.

Ray Reddick’s meticulous genealogical research over decades has made it possible for the West End Museum and Reckonings project to co-create this family oral history. Part Two of the Reddick Story (forthcoming) will tell the story of Ruthena Felton King Reddick, Ray’s grandmother, and the life of Ray Reddick.

Article by Adam Tomasi, Rose-Laura Meus, Ray Reddick, and the Reckonings Project

Source: Claire Kluskens, “Federal Records that Help Identify Former Enslaved People and Slave Holders,” National Archives, December 2021, https://www.archives.gov/files/calendar/genealogy-fair/2018/2-kluskens-handout.pdf; Town of Annapolis Royal, “First Nations,” https://annapolisroyal.com/visitors/first-nations/, accessed May 16, 2022; Annapolis Heritage Society, “History of Annapolis Royal,” https://annapolisheritagesociety.com/community-history/history-annapolis-royal/, accessed May 16, 2022; Adam Tomasi, “Adelaide Cromwell: Mapping Community in the Black West End,” The West End Museum, 2022, https://thewestendmuseum.org/article/adelaide-cromwell-mapping-community-in-the-black-west-end/; Adelaide Cromwell, The Other Brahmins: Boston’s Black Upper Class, 1750-1950 (Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 1994), page 68; Jennifer Page, “William H. Carney,” National Park Service, accessed July 11, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/articles/william-h-carney.html; “To Observe Anniversary of Shaw’s Charge Monday,” The Boston Globe, July 13, 1921, page 7; 1935 Boston Globe obituary provided by Ray Reddick; “Finding Voices in the Silence: Tracing the History of Boston’s Black Community at Forest Hills Cemetery,” Forest Hills Educational Trust, http://www.foresthillstrust.org/about_fhc/voices/voices_findings.html, accessed August 10, 2022; “Ruthena Felton King,” Family Search, https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/2Q1D-9NT/ruthena-felton-king-1893-1985, accessed August 10, 2022.