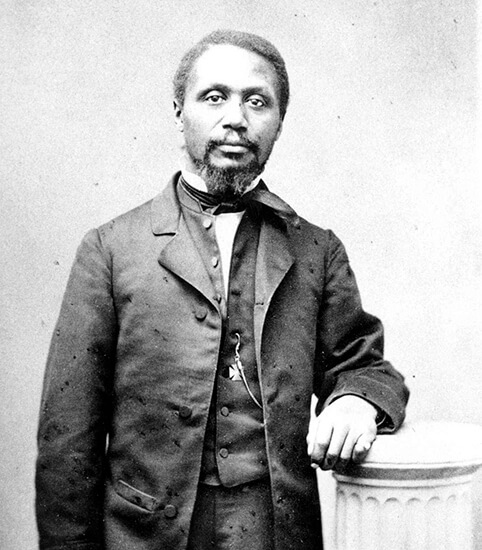

Robert Morris

Robert Morris (1823-1882) was a prominent civil rights leader in Boston and the United States’ second African American lawyer. He built a successful career as a lawyer handling civil, criminal, and civil rights cases, while putting his life and livelihood on the line for causes he believed in: abolition, the protection of freedom seekers, the desegregation of schools, the integration of militias, equal rights for women, and fair representation for immigrants.

Robert Morris was born in 1825 in Salem, Massachusetts, the son of Yorkshire Morris, a bootblack and waiter, and Mercy Morris, a homemaker who was active in mutual aid organizations. He was the grandson of a man known as Cumono, who was trafficked across the Middle Passage as a boy, arrived in Ipswich in the mid-1700s, trained as a carpenter, and helped to build the town’s first church.

Morris was thirteen years old and working as a waiter when abolitionist lawyer Ellis Gray Loring negotiated with Morris’ mother to have him work in his Boston home as his assistant and copyist. After a few years, Morris began a legal apprenticeship. On February 2, 1847, Morris was admitted to the Massachusetts bar, becoming the second African American lawyer in the United States. In under a year, he would become the first Black lawyer in the country to argue and win a jury trial.

Morris lived with the Lorings near Boston Common for ten years until marrying Catharine H. Mason. The couple had a home in Chelsea, Massachusetts and Robert kept an office on Boston’s Washington Street, but he was well known on the North Slope and in the West End where much of his work took place.

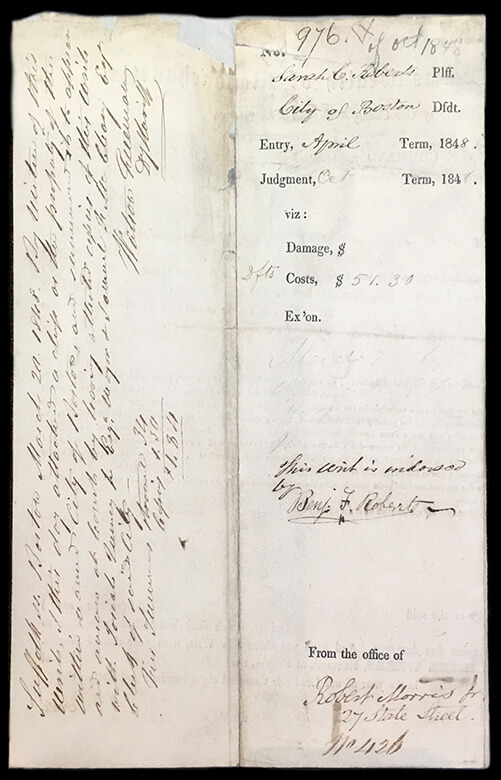

Likely inspired by his older sister, Harriet, who had become the first African American student to attend a public high school in Salem, Morris began his fight for school integration in 1848, when he was hired by printer and activist Benjamin Roberts. Roberts’ daughter, Sarah C. Roberts, had been expelled from the Otis School because of her race, after being allowed to enroll and attend for three weeks. As a result, five-year-old Sarah would have to go back to walking past several White public schools on her way to attend an African American public school, the Abiel Smith School, on Belknap (now Joy) Street.

Morris filed a lawsuit against the City of Boston on Sarah’s behalf and hired as his co-counsel Charles Sumner, a year prior to his election to the Senate. In March 1850, Judge Lemuel Shaw of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court upheld school segregation and in doing so provided precedent for the “separate, but equal” argument used in later legal cases. While this ruling dealt a significant blow to Boston’s equal school movement, due to the tireless work of desegregation activists, including Morris and William Cooper Nell, the Massachusetts legislature outlawed public school segregation five years later, in 1855.

“The cause of equal school privileges originated with us. Unaided and unbiased we commenced the struggle.”

– Benjamin Roberts

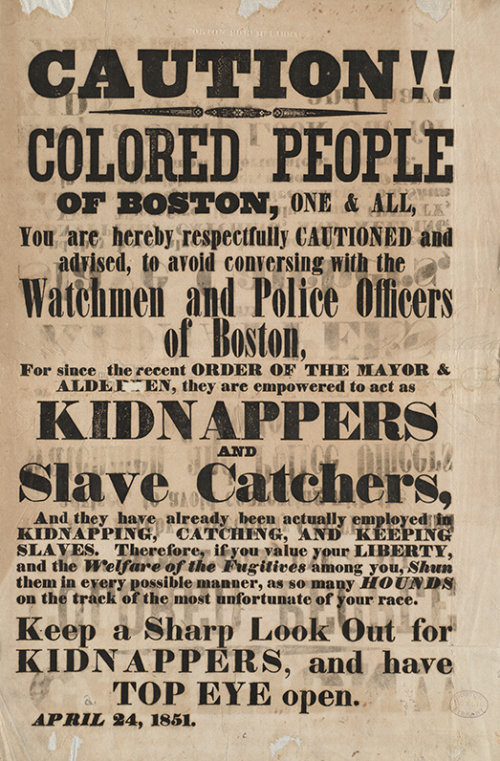

The same year as the crushing Sarah Roberts v. City of Boston defeat, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was enacted by Congress. Part of the congressional “Compromise of 1850,” this act aggressively upheld and extended the provisions of the 1793 Fugitive Slave Law. Law enforcement was required to arrest people suspected to be escaped slaves and any person aiding a fugitive could receive six months’ imprisonment and a $1,000 fine. The Fugitive Slave Act gave Black people in the North no defense against capture and enslavement if they were pursued; any enslaver or hired hunter could arrest an assumed fugitive. As a response, Morris and many of his abolitionist peers established the Boston Vigilance Committee to protect freedom seekers.

“Let us be bold, if any man flies from slavery, and comes among us. When he’s reached us, we’ll say, he’s gone far enough.”

– Robert Morris in The Liberator, August 13, 1858

Just a few months after the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, Morris represented Shadrach Minkins, who had fled to Boston from slavery in Virginia. Almost a year after escaping bondage, Minkins had been arrested by federal marshals while working at the Cornhill Coffee House in Boston. Morris filed a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of Minkins, but this was refused by the judge. Subsequently, White and Black activists – including Lewis Hayden – stormed the courthouse and rescued Minikins. With the help of members of the Boston Vigilance Committee, Minkins was able to flee to Canada. Morris and Hayden were indicted in federal court for aiding the escape. After a hung jury, the case was dismissed and Morris was acquitted. Morris proclaimed innocence and the story of his involvement in the rescue wouldn’t be told until 1889 after Lewis Hayden’s death: Hayden and Morris had rushed Minkins from the courthouse to the attic of Elizabeth Riley at 70 Southac Street, and from there the Underground Railroad helped guide Minkins to Canada.

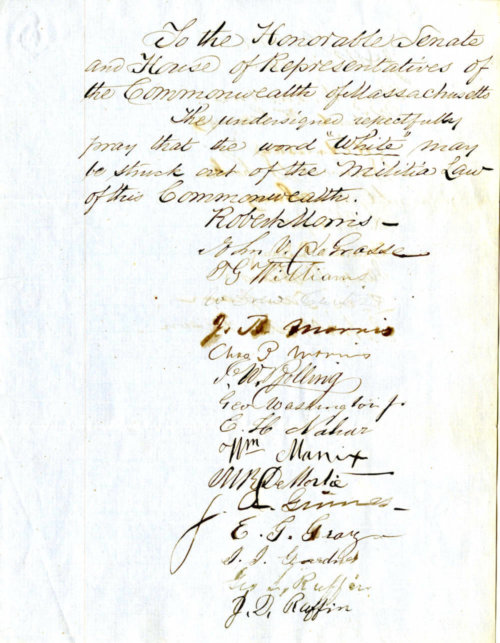

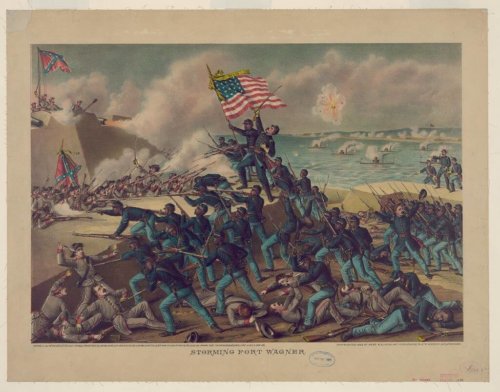

Morris’s fierce commitment to fighting for equality extended to the militia. In 1854, when Black Bostonians were denied the right to bear arms for their country, Morris and William Cooper Nell petitioned the legislature to remove “white” from the state’s militia laws and create a Black military company, which they called the Massasoit Guards. Despite the efforts of abolitionists and prominent supporters such as Governor John Andrews, it would be a decade until the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment marched through the streets of Boston on their way to fight for the Union. To Morris’s profound disappointment, equality was not achieved – the 54th served under the command of white officers and had to fight not only the Confederacy, but also their own government for equal pay.

“Don’t you call me ‘brother’ until you have taken the word ‘white’ out of the Constitution!”

– Robert Morris during a militia debate at the Twelfth Baptist Church

Morris was also an energetic and enthusiastic supporter of women’s civil and political rights. As early as 1853, he signed a petition to strike the word “male” from the Massachusetts Constitution and supported suffrage efforts.

Despite struggling with discrimination from many Irish Bostonians and the difficult decision to leave the Methodist church, Morris began attending Catholic services with Catharine in the 1850s. While teaching Sunday School, Robert met a child named Patrick Collins, an impoverished Irish immigrant. As Ellis Gray Loring had done for him, Morris employed twelve-year-old Patrick in his office and eventually became his mentor. Patrick Collins would later go on to Harvard Law School and became mayor of Boston in 1902.

In the late 1860s, the Morris family moved to the South End and attended the Church of the Immaculate Conception, a Jesuit-run church that was associated with Boston College. In 1868, Morris and his family traveled around Europe and even had a personal audience with the Pope at the Vatican. After building strong relationships in the Irish Catholic community, which was remarkable for the time, Morris was Baptized and received into the Catholic Church in 1870. He became a trusted criminal defense lawyer to many members of Boston’s Irish community and would become known by some as the “Irish Lawyer.”

Robert and Catharine had three children, but only one lived beyond the age of ten. Studying under his father, in England and France, and at Harvard Law School, Robert Jr. was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar in 1874. He was the first second-generation Black lawyer in the country and practiced with his father in their office near City Hall.

Robert Morris represented clients until he passed away on December 12, 1882. Patrick Collins and Lewis Hayden were among his pallbearers at the Church of the Immaculate Conception. His son Robert Jr., age 35, died of typhoid fever just two weeks later. Catharine Morris died at the age of 70 in 1895, and named the Church of the Immaculate Conception as beneficiary of her estate.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Kabria Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (NYU Press, 2019); Boston Athenaeum, “Robert Morris Papers”; Boston College, Robert Morris: Civil Rights Lawyer & Antislavery Activist; Stephen Kendrick and Paul Kendrick, Sarah’s Long Walk: The Free Blacks of Boston and How Their Struggle for Equality Changed America (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004); National Park Service, “Robert Morris.”