Sarah C. Roberts

At the age of five, Sarah Roberts was at the center of a lawsuit against racially segregated public schools in Boston in 1847. Roberts, a Black girl, was denied the equal right to attend the public school of her choice, forced instead to walk past five public schools to the Black-only Abiel Smith School in the old West End.

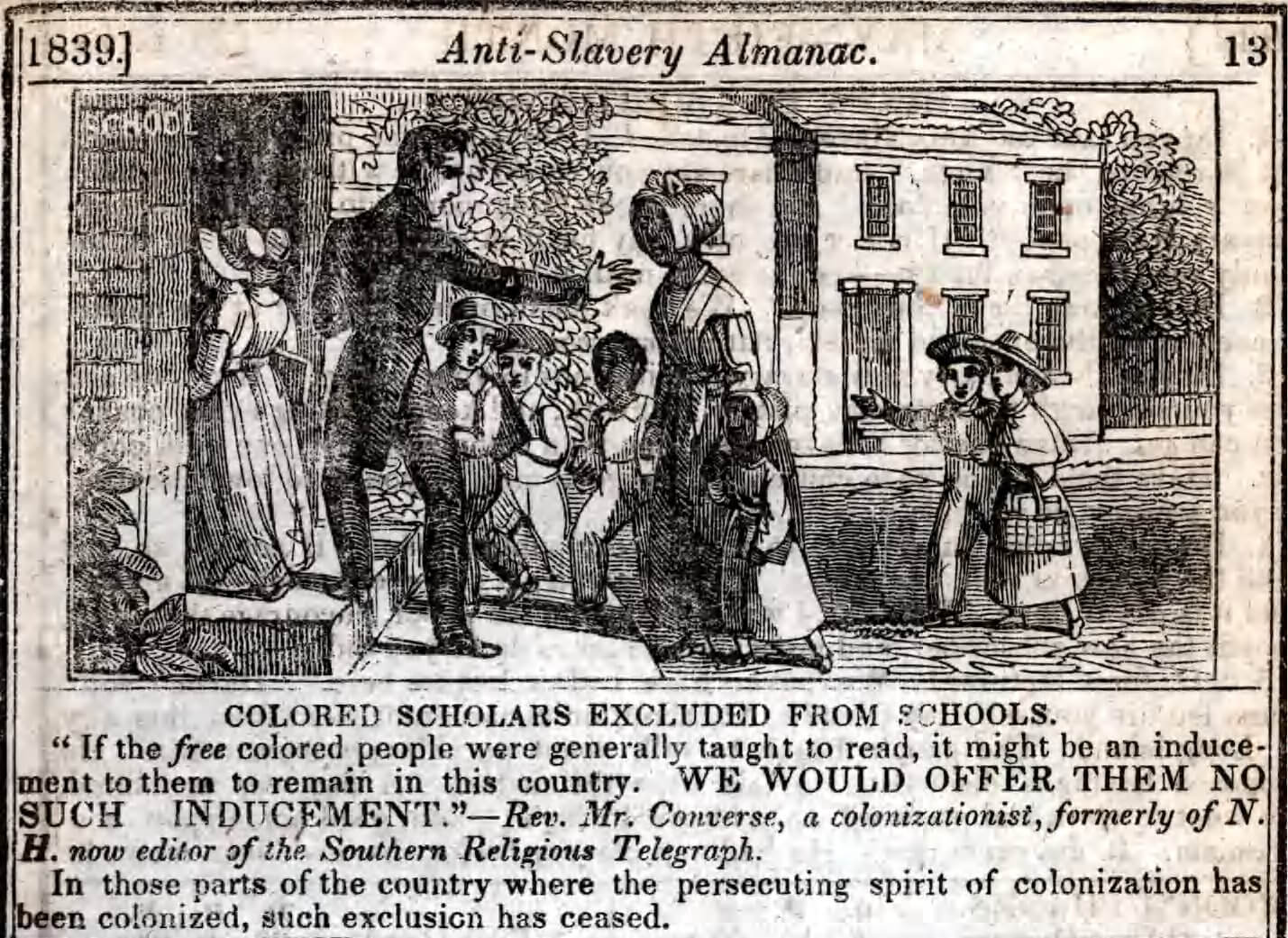

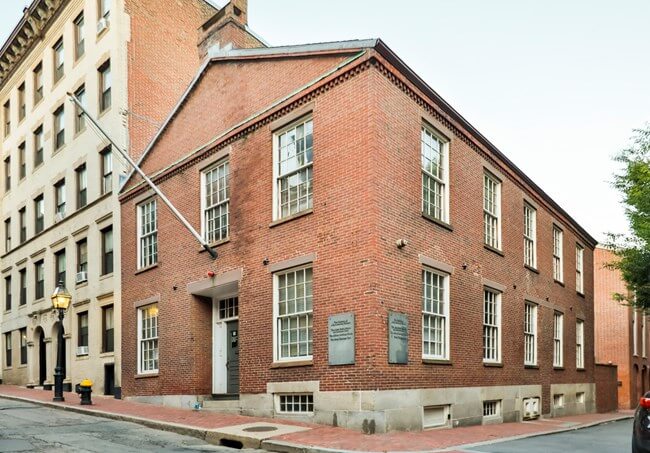

Sarah C. Roberts was born to Benjamin and Adeline Roberts in 1842. Though the Roberts family lived at 3 Andover Street near the docks in the historic West End, Sarah, a Black girl, was required by city and state officials to attend the Abiel Smith School, a racially segregated public elementary school for Black children. The Abiel Smith School moved to its ultimate location on Belknap Street in the old West End in 1835. From 1844 to 1846, Black families petitioned Boston’s Primary School Committee to close the Abiel Smith School and integrate Boston’s public schools, not only because the city grossly neglected to provide Black schools with proper funding and repairs, but also because racially segregated public schools stigmatized Black children and were intended to inculcate feelings of inferiority. In 1847, Benjamin and Adeline Roberts decided to enroll Sarah, then five years old, at the Otis School, a ‘whites-only,’ co-ed public school closest to their home.

The Otis School initially admitted Sarah Roberts, and her first few weeks at her new school appeared to go smoothly. But after her parents attempted to enroll Sarah’s nine-year-old brother, Benjamin Jr., at the Otis School, the Primary School Committee was up in arms at the prospect of admitting one more Black child to a white school. The Otis School proceeded to expel Sarah, and a police officer took her off school grounds. After many subsequent denials of Sarah and Benjamin Jr.’s access to the public schooling of their choice, Benjamin Sr. sued the city in 1847 to challenge its denial of equal school rights for Black children. “Equal school rights” was the language of choice for nineteenth-century Black people fighting for school desegregation (the latter being a twentieth-century phrase), according to Northeastern University historian Kabria Baumgartner in In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (2019). Benjamin Roberts, Sr. chose to sue on Sarah’s behalf instead of his son for strategic reasons. Baumgartner explains:

Benjamin Sr.’s decision to sue on Sarah’s behalf, and not on his son’s, was strategic. Benjamin Jr. had been outright denied entry to the Otis School….Benjamin Sr. relied on social assumptions tied to Sarah’s gender and age: a five-year-old girl might produce a more positive outcome compared to a nine-year-old African American boy. Such was the case when Sarah attended the Otis School for a few weeks. The decision to sue on Sarah’s behalf would transform her into an icon for educational justice.

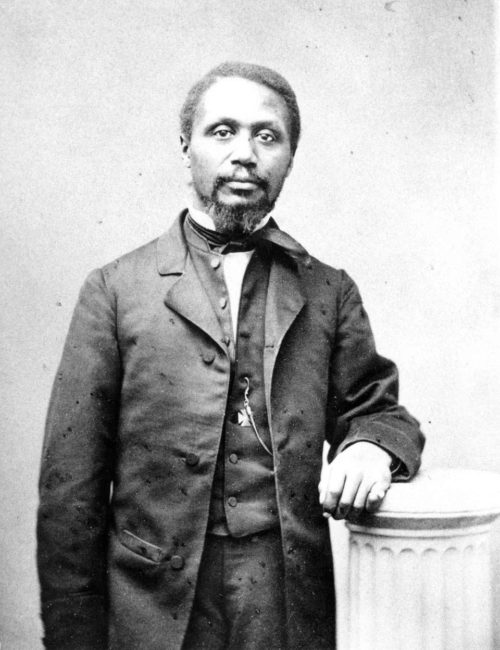

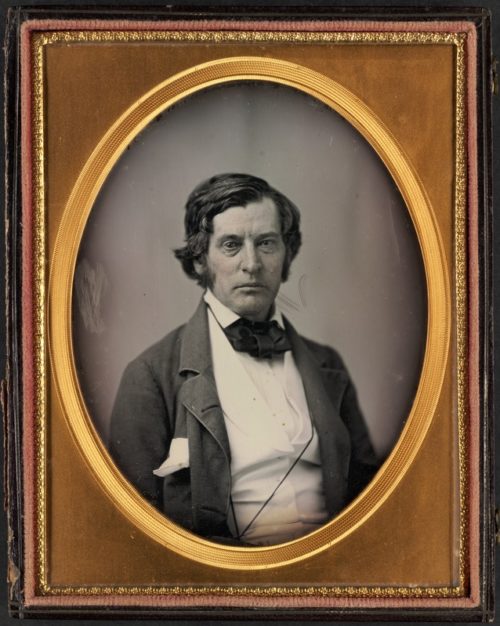

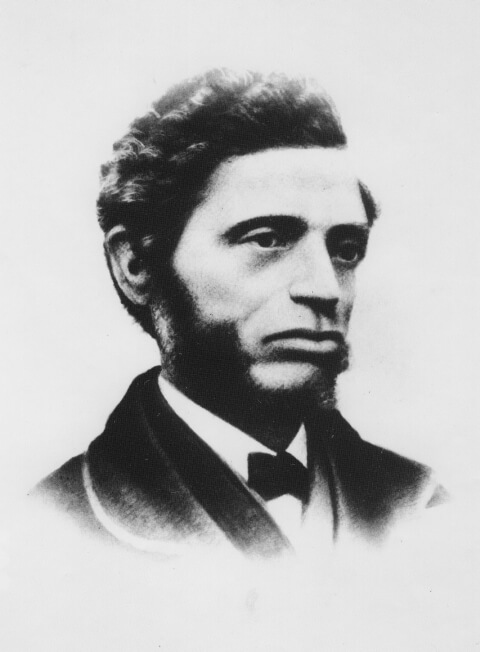

In the lawsuit, Sarah Roberts was represented by Robert Morris, one of the first Black men to become a practicing lawyer in Massachusetts, and Charles Sumner, abolitionist and future Senator for Massachusetts. Morris and Sumner presented their case on many bases: that a state statute from 1845 established that children “unlawfully excluded from public school shall recover damages,” and that Massachusetts’ constitutional guarantee of equality under the law made racially segregated schools illegal. One of the unequal burdens Morris and Sumner emphasized was that school officials were forcing Sarah to walk past five different public schools to reach the Abiel Smith School from her home, instead of allowing her to attend the closest public school (the whites-only Otis School). The Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas ruled in favor of Boston’s school committees in 1848, and Roberts’ counsel appealed to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. But in March 1850, Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw ruled against Sarah Roberts on the basis that Boston’s public schools had the right to classify and separate students according to race.

Shaw’s ruling in Sarah Roberts v. City of Boston would become infamous for its application as precedent by the United States Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, when the Court ruled in 1896 that “separate but equal” schooling was constitutional. Yet Black families in Boston nevertheless succeeded in their grassroots challenge to segregated schools and their demand for equal school rights. Benjamin Sr. joined activists such as William Cooper Nell, the Black abolitionist and printer from the north slope of Beacon Hill (part of the historic West End), in large petition drives that continued to fight for equal school rights. The Massachusetts legislature then passed a law in 1855 that ended de jure racial segregation of public schools. Nell responded to the news with strong praise. As a former student of the Smith School, Nell understood the impact that equal school rights would have on future generations: “On the morning preceding their advent to the public schools, I saw from my window a boy passing the exclusive Smith School, where he had been a pupil, and, raising his hands, he exultingly exclaimed to his companions, ‘Good bye forever, colored school! Tomorrow we are like other Boston boys!” The Abiel Smith School closed quickly after the first integrated school year began.

Although all of Boston’s Black children benefited from the achievement of equal school rights, it was Black women and girls, including Sarah Roberts, who often stood at the forefront of campaigns for civil rights in education. Black mothers went from school to school on September 3, 1855 (the first day of school that year) to make sure that their children were properly admitted and welcomed. Nell acknowledged as much in a celebration of the recent civil rights achievement at the Twelfth Baptist Church, on December 17, 1855, when he told the audience that, “Truth enjoins upon me the pleasing duty of acknowledging that to the women, and the children also, is the cause especially indebted for success.” The Roberts family moved from Boston to Cambridge, Somerville, and Chelsea during the 1850s, and moved back to Boston in 1865 when Sarah was twenty-two. In 1867, Sarah moved with her husband John Casneau (whose parents came from the West Indies) to New Haven, Connecticut, and they divorced in 1878.

Sarah Roberts died of cancer in New Haven on April 27, 1896. She was a symbol of, and a key contributor to, the fight for equal school rights at a young age, and connected to the larger network of civil rights activism that thrived in the nineteenth-century West End.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Kabria Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (NYU Press, 2019); Paul Kendrick and Stephen Kendrick, Sarah’s Long Walk: The Free Blacks of Boston and How Their Struggle for Equality Changed America (Beacon Press, 2004); Long Road to Justice; National Park Service; BlackPast; Native Northeast Portal