Southworth & Hawes: Early Photography in Boston

The partnership of Albert Sands Southworth and Josiah Johnson Hawes revolutionized early photography in the United States, particularly through their exceptional portrait daguerreotypes. Operating from 1843 to 1861, their renowned Scollay Square studio attracted elite clientele, including prominent political, intellectual, and artistic figures, as well as many notable West Enders. Their streetscapes of Scollay Square, the West End, and other Boston neighborhoods, and their commissioned works on historic events, documented Boston during a period of physical and cultural change.

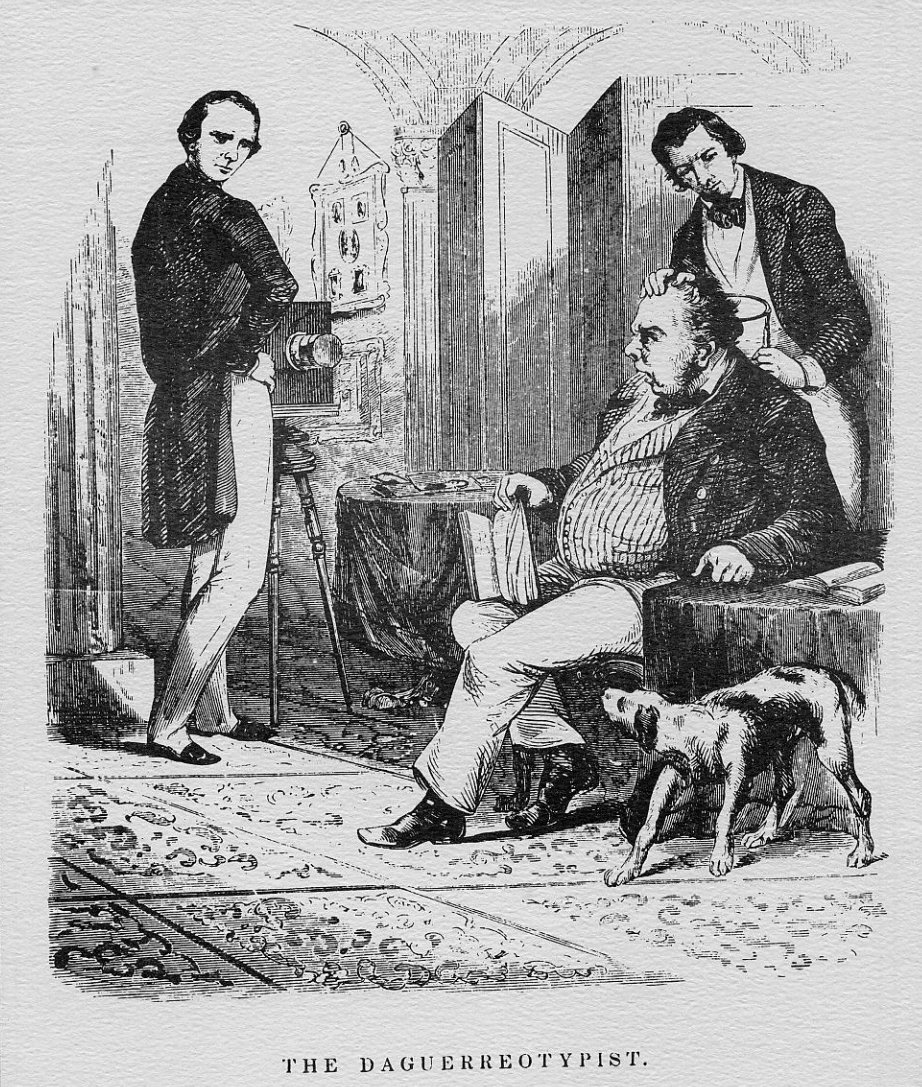

On January 7, 1839, painter Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) presented his new invention to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris: the “daguerreotype.” Daguerre’s novel photographic technique used silver-plated copper sheets sensitized with iodine vapors, which were exposed in a box camera, developed in a mercury solution, and stabilized with salt water. The result was a unique photographic image that shocked both scientists and artists. The process quickly spread around the world, in part due to traveling lectures by Daguerre’s representatives. One such ambassador, François Fauvel Gouraud (1808–1847), delivered lectures on daguerreotypy in Boston in March and April of 1840. While they did not know each other at the time, both Albert Sands Southworth (1811–1894) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (1808–1901) attended Gouraud’s lecture and demonstration series. Three years after this lecture, Southworth and Hawes entered into a partnership, together operating one of the most renowned photography studios in the United States. From 1843 to 1861, their firm produced exceptional portrait daguerreotypes, attracting a distinguished clientele of political, intellectual, and artistic luminaries.

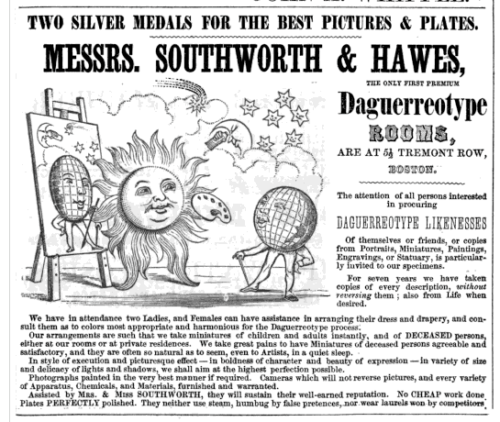

Josiah Johnson Hawes, from East Sudbury (now Wayland), Massachusetts, worked as a farmer and carpenter before becoming a self-taught artist specializing in portraits, landscapes, and miniatures on ivory. Albert Sands Southworth was from Vermont but, by the time of Gouraud’s lecture, had established himself as a pharmacist in Cabotville (now Chicopee), Massachusetts. Gouraud’s photographic demonstrations, however, changed the trajectory of both mens’ careers: that same year, Southworth left for New York to study daguerreotypy with Samuel Morse, and Hawes gave up painting in 1841 to pursue the new photographic technique. Within a year, Southworth had opened a daguerreotype studio with Joseph Pennell in Boston at 60 ½ Court Street. In 1842, he relocated to 5 ½ Tremont Row (later renumbered 19 Tremont Row). When Pennell left the firm in 1843, Josiah Johnson Hawes replaced him, and in 1846 the firm was renamed Southworth & Hawes. The esteemed eighteen-year partnership of Southworth and Hawes was born.

Their studio at the junction of Tremont Row and Brattle Street, like Southworth’s previous studio on Court Street, was in Scollay Square. Scollay Square, and surrounding Washington and Sumner Streets, was a bustling commercial area, near where the painters John Singleton Copley, John Trumbull, and Washington Allston once had their studios, and where many contemporary lithographers, engravers, and painters still did. Southworth and Hawes were among the first daguerreotypists in Boston, and quickly became the most fashionable portrait studio in Boston. In their Tremont Row space, they worked from three adjoining lofts. In one, they installed a large skylight, which allowed them to more easily play with light and shadow in their portraits. Southworth’s sister and brother also worked at the Southworth & Hawes’ studio, helping the partners in various capacities: Nancy (who later married Hawes) hand-colored some of the daguerreotypes, and Asa managed the waiting room.

Southworth and Hawes remained busy tinkering and refining their process. They patented the Grand Parlor Stereoscope camera; created a movable camera back that could be used to correct parallax; and, by 1856, devoted much of their efforts to innovating with wet plate collodion photography and paper prints. The partners also made money by offering instruction on daguerreotyping and selling photographic supplies to studios from Massachusetts to Pennsylvania.

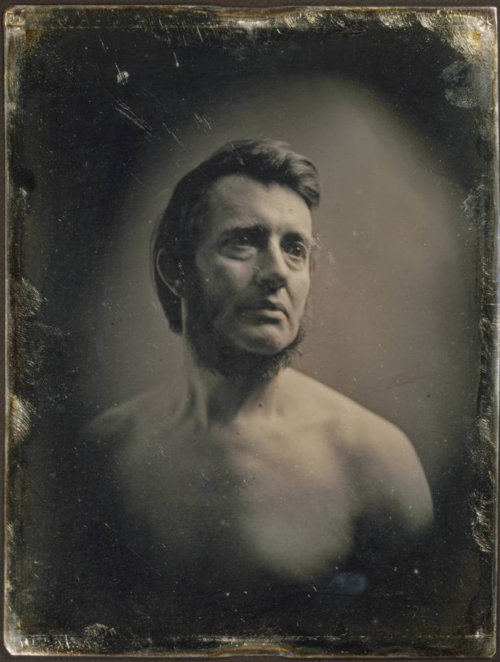

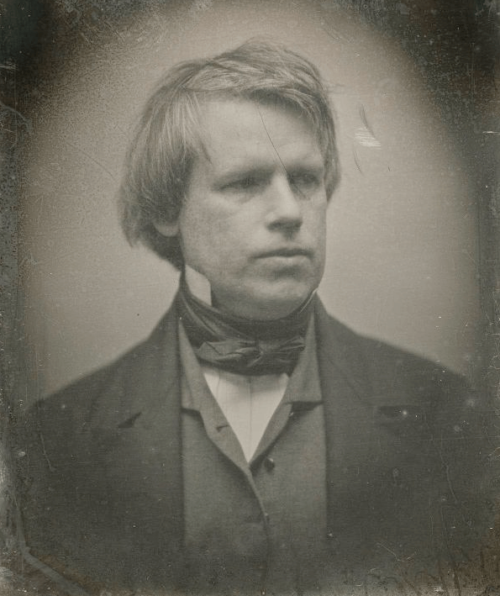

Southworth & Hawes specialized in portraiture for Boston’s elite and visiting celebrities. Politicians, authors, artists, and abolitionists traveled to the Scollay Square studio, drawn in by Southworth & Hawes’ prowess at capturing likeness in a picturesque manner. West End-related notables Louisa May Alcott, William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, James and Annie Adams Fields, and Sally Foster Otis all sat to have their portraits done at Southworth & Hawes. Other well-known sitters included Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Quincy Adams, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Margaret Fuller, Susan B. Anthony, Dorothea Dix, and Daniel Webster, among many others.

Their high prices ensured that Southworth & Hawes maintained an elite clientele. One of their whole-plate portrait daguerreotypes cost $15 and oversized plates could cost up to $50. In comparison, other studios usually used a standard ⅙-plate size and charged $2. Southworth & Hawes’ large-format plates were not only expensive, but required the highest degree of technical mastery. Often, the partners made multiple exposures, changing the sitter’s and camera’s position to perfect the daguerreotype’s composition. The sitters were then allowed to pick their favorite image, and the other versions were held in the Scollay Square studio.

Through their portraits, Southworth and Hawes sought to capture not only likeness but “the life, the feeling, the mind, and the soul” of their sitters. The aura of the image also had to be appropriate for the photograph’s ultimate environment and audience. The partners outlined this ethos in an advertisement, stating: “A likeness for an intimate acquaintance or one’s own family should be marked by that amiability and cheerfulness, so appropriate to the social circle and the home fireside. Those for the public, of official dignitaries and celebrated characters admit of more firmness, sternness and soberness.”

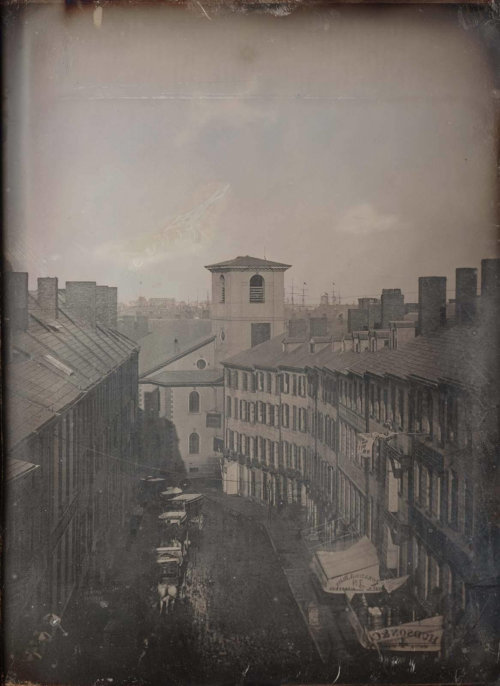

Hawes and Southworth also created photographs of city views. Hawes, who did much of this work, usually conducted his architectural photographs early or late in the day, so he could achieve portrait-like images of buildings without people in the way. Most of these were taken in the wealthy sections of Boston, as there were more people there able to commission the photographs or buy the prints. Today, these photographs provide an invaluable record of Boston’s streets and culture from 1840 through the 1870s, a time of rapid change and growth in the city. Many of these photographs survey streets and buildings in Scollay Square and the neighboring West End, including images of Bowdoin Street, Bowdoin Square, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charles Street Jail, the Eastern Railroad Depot on Causeway Street, Court Street, the Beacon Hill Reservoir, the Phillips School, and the African Meeting House.

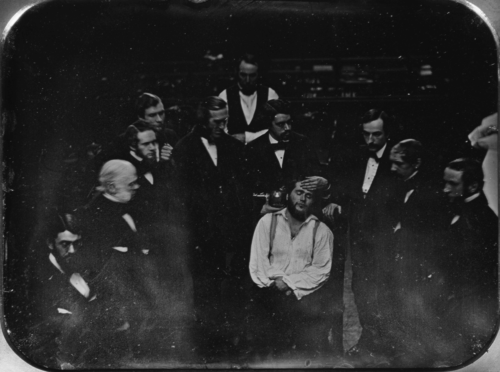

While most of these city-view photographs were of exteriors, Hawes also created some images of the buildings’ interiors, including at Massachusetts General Hospital. Southworth and Hawes, for instance, were commissioned to record several ether surgeries inside the (now-called) Ether Dome at MGH. This includes a daguerreotype of the reenactment of the first administration of ether at MGH on October 16, 1846.

In 1849, Southworth left for the California gold fields, and Hawes ran the studio alone until Southworth’s return in 1851. With the advent of the collodion process, a photographic technique with a negative, daguerreotypy declined. Southworth and Hawes began using the collodion process in 1854 and by 1859 they were exclusively using it.

In 1861, Southworth left the partnership and for a few years ran a photography studio of his own. He soon abandoned his studio to become a graphology specialist, using photography to study handwriting for forensics. He died in 1894 in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Hawes continued to work in photography at the same Tremont Row address until his death in 1901. On August 10th of that year, The New York Times published an article memorializing Hawes’ life and prolific career. In it, they described him as “the oldest photographer in the world.” Over a century later, both Hawes’ and Southworth’s legacy endures, preserved in their iconic portraits and contributions to the evolution of photographic art.

Article by Grace Clipson, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: George Eastman House Collection, A History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present (Taschen, 2005); George Eastman House, Young America: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes, 2005; Getty, “Southworth & Hawes”; Ellen Handy, “Transfigurations: Southworth and Hawes, Reproduced Images and the Body,” Artium Quaestiones (2022); Rajesh Parsotam Haridas, “Photographs of Early Ether Anesthesia in Boston: The Daguerreotypes of Albert Southworth and Josiah Hawes,” Anesthesiology July 2010, Vol. 113, 13–26; Rachel Johnston Homer, The Legacy of Josiah Johnson Hawes: 19th Century Photographs of Boston (Barre, Mass.: Barre Publishers, 1972); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Lemuel Shaw”; The New York Times, August 10, 1901; Becky Simmons, “Southworth & Hawes,” George Eastman House.