Spiritualism in Boston

In the late 1840s, Americans began to flock to the Spiritualist movement. Boston’s middle and upper class, in particular, became enthralled with Spiritualism, and the city became a center for séances, mediums, and spiritualist newspapers from the 1850s to the mid-1920s.

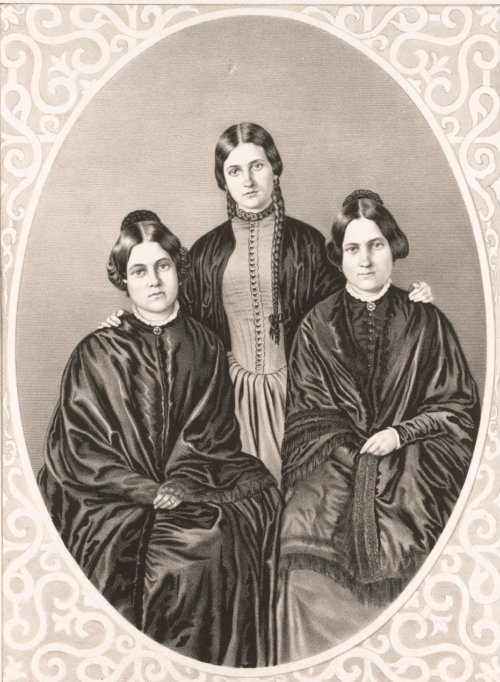

The modern Spiritualist movement, founded on the belief in the soul’s immortality and the ability to communicate with the deceased, reached the height of its popularity in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its growth was sparked by the Fox sisters of Rochester, New York, who, beginning in 1848, allegedly communicated with spirits through knocking sounds. The sisters’ supernatural communications quickly made them celebrities, and the widespread popularity of the story led to an explosion in spiritualist activity across the country.

The Spiritualist doctrine that evolved was attractive to those who felt restricted by society and religion. Free of strict orthodoxy, hierarchy, or a fearsome hell, Spiritualists worshiped individual conscience and were encouraged to seek manifestations of the departed. Each person was believed to be a conduit for the divine, a tenet that allowed women to hold public meetings and occupy leadership positions, during a time when this usually was not the case. The ethos of the movement generally appealed to reformers, and spiritualists were largely supportive of abolitionist and suffragist movements. Reformers often found that spirits favored their ideas of the abolition of slavery and equal rights for women, which were communicated through a medium, typically a woman, while in a trance. Divine sanction made radical ideas less objectionable. Many women invited to speak at suffrage meetings often also made their living as “trance speakers.”

By the early 1850s, Boston had become a center for Spiritualism. It was also where one of the first, and the longest-running, Spiritualist newspapers was first published in 1857: the Banner of Light. The Banner published essays on spiritual, philosophical, and scientific subjects; chronicled séances, lectures, and retreats; and ran advertisements for mediums and treatments for physical and psychic ailments. It also printed messages from the dead and held free séances in its Circle Room three times per week, conducted by resident mediums like Fanny Conant, Jennie S. Rudd, and Mary Theresa Longley. Susan B. Anthony was among the paper’s readers and advertisers, posting meetings for the Suffrage Association.

The paper’s offices were located at 5 Brattle Street until 1861, then 158 Washington Street, and then 11 Hanover Street, following the Great Fire of 1872. A report of the first Banner séance after Great Fire follows:

The loss of our Circle Room by fire necessarily involved a suspension of our Free Circles for a time; but it will, we feel assured, be a great gratification to our numerous readers to ascertain that these séances have been resumed. The spirits who controlled the medium on this occasion, for the purpose of sending messages through our columns to their loved ones of earth, were Alice Peterson, of Philadelphia, to her mother; Mary Walters, to her sister; Horace Greeley (in regard to his will); Janjes R. Tibbetts (a Boston fireman who lost his life endeavoring to rescue a fellow-being from the flames); Charles Allen Welch, of Boston (who reports that he was recently lost, at sea).

In the same issue, an essay by a Spiritualist declared that the fire was the fulfillment of a prophecy, along with the floods, pollution, and illnesses of the time (a popular sentiment among readers). The Banner eventually moved to the Back Bay and later Cambridge.

The Banner’s longest serving medium, Fanny Conant, was well-known in the community and believed to be especially skilled at lifting the veil between the physical and spiritual worlds. She held many public and free séances, but also made herself available for private spirit circles, some hosted at homes on Joy Street and Cambridge Street in the West End.

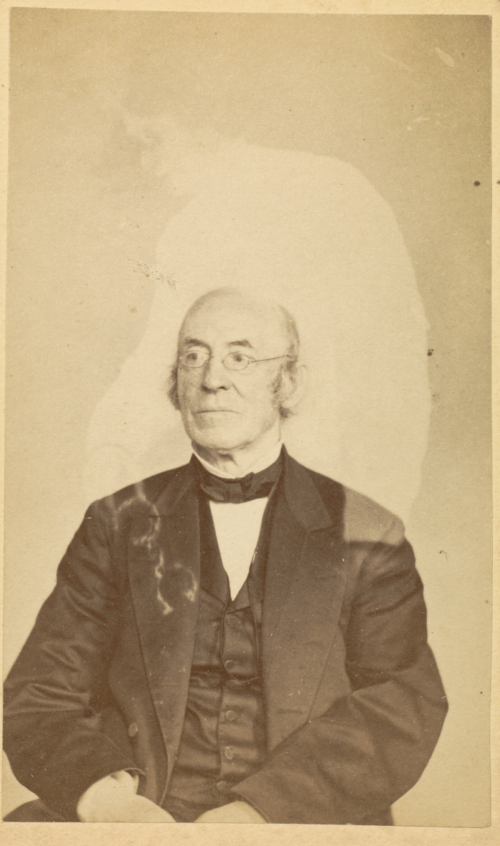

Her contemporary, William Mumler, was an engraver on Washington Street, who became known as a “spirit photographer” after developing a self-portrait that revealed an image of his deceased cousin by his side. He grew a business providing the spiritually-curious solace in the confirmation of the afterlife. Mumler’s most famous photograph was of Mary Todd Lincoln with the ghost of her husband Abraham Lincoln. Eventually, Mumler was taken to court for fraud, where the showman PT Barnum testified against him. While not found guilty, it ended his career as a spirit photographer.

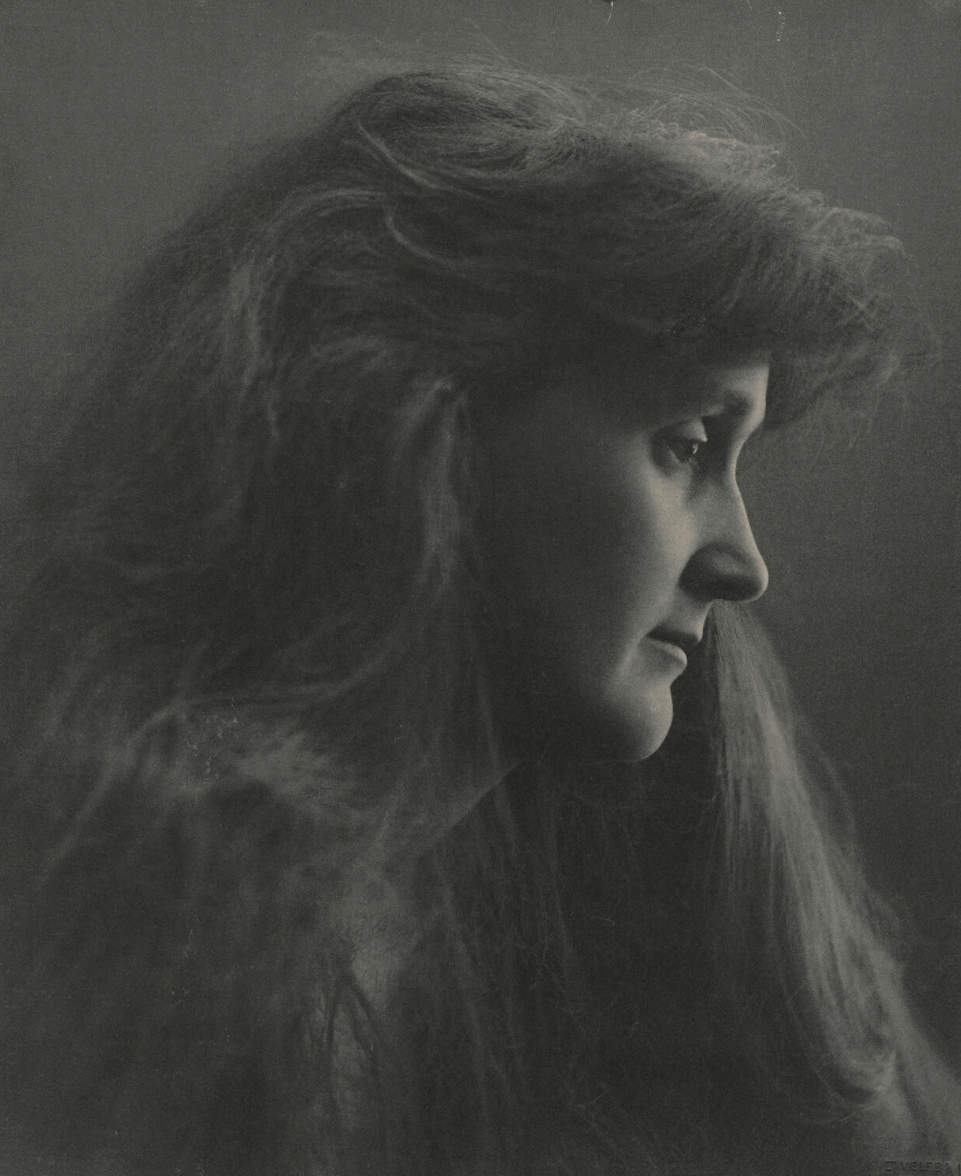

Leonora Piper was one of the most famous and scrutinized mediums, and for a time lived at 40 Pinckney Street in the West End, where she gave private readings and spirit meetings. Rev. Dr. Minot J. Savage, who had one such meeting with Leonora, described:

I had sittings with Mrs. Piper years ago, before the society was organized or her name was publicly known. On the occasion of my first visit to her, she was, I think, in a little house on Pinckney Street in Boston. At this time she went into a trance, but talked instead of writing. The first person who claimed to be present was my father. He had died in Maine at the age of ninety. He had never lived in Boston, nor, indeed, had he visited there for a great many years, so that there was no possibility that Mrs. Piper should ever have seen him and no likelihood of her having known anything about him. She described him at once with accuracy, pointing out certain peculiarities which the ordinary observer, even if he had ever seen him, would not have been likely to notice.

While Leonora was suspected of fraud, it was difficult to prove. She gave her last séance in 1911.

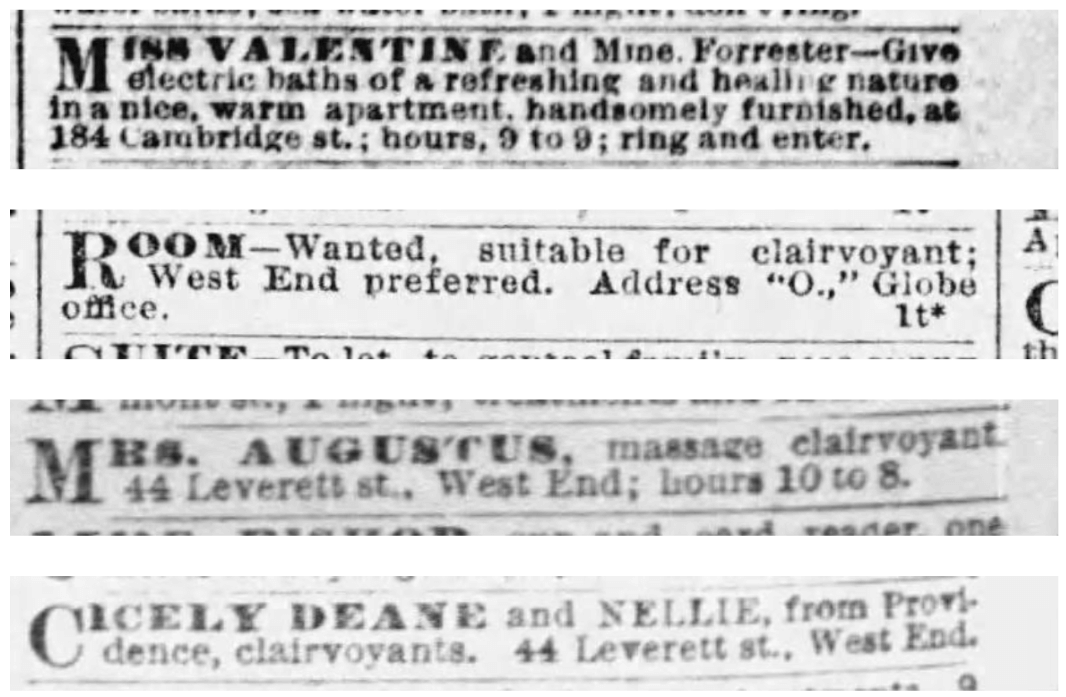

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Boston Globe ran numerous advertisements for clairvoyants, astrologers, and spiritual healers with services ranging from séances to fortune telling to electric baths, which used frictional electric machines to build a “curative charge” in the body. Many of these spirit workers had apartments on Green, Cambridge, Lynde, and Leverett Streets in the West End.

As science evolved; mortality declined; allegations of fraud rose; and women, who once expressed their political views as conduits for the dead, could more easily speak for themselves, the practicing Spiritualist community dwindled in Boston, particularly after the mid-1920s.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: The Banner of Light (accessed via The International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals); Ann Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Indiana University Press, 2001); Isaac K. Funk, The Widow’s Mite and Other Psychic Phenomena (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1904); Peter Manseau, The Apparitionists: A Tale of Phantoms, Fraud, Photography, and the Man Who Captured Lincoln’s Ghost (Houghton: Mifflin Harcourt, 2017); Dee Morris, Boston in the Golden Age of Spiritualism: Séances, Mediums & Immortality (The History Press, 2014).