Susan Paul: Abolitionist, Educator and Author

Susan Paul (1809 -1841) worked as an abolitionist, educator, and author from the north slope of Beacon Hill in the West End. She fought against slavery in every aspect of her professional life through her education of African American students, the inspirational music performed by her choir, and her landmark work, The Memoir of James Jackson, the earliest known prose narrative and biography by an African American woman in the United States.

Susan Paul was born in 1809 in Boston to Reverend Thomas Paul (1773–1831) and Catherine Waterhouse Paul. Thomas Paul was the first Reverend of the African Baptist Church, the first Baptist congregation in the North that later occupied the African Meeting House on the north slope of Beacon Hill in the historic West End. Catherine Waterhouse Paul was an educator at a school on Southac (now Phillips) Street that later relocated to the family home at 26 George Street (now 36 West Cedar Street) on the flats between Beacon Hill and the West End. As Freewill Baptists, the Pauls condemned slavery as a threat to man’s salvation and an act of defiance against God’s divine plan. They believed that it was the religious duty of all Christians to fight slavery as part of their daily work.

Susan was heavily influenced by her parent’s religious philosophy, their leadership roles in the evangelical abolitionist movement, and their association with William Lloyd Garrison and other activists. She became a teacher and taught at Boston Primary School No. 6 and later at the Abiel Smith School on Joy Street. Her older sister Anne and younger brother Thomas, Jr. also became educators. In the classrooms of her segregated schools, Susan instructed both freeborn and formerly enslaved students in character building, civic engagement, piety, obedience and morality. Students were also exposed to the evils that enslaved children had to endure in the South, and taught that the institution of slavery was a violation of God’s law.

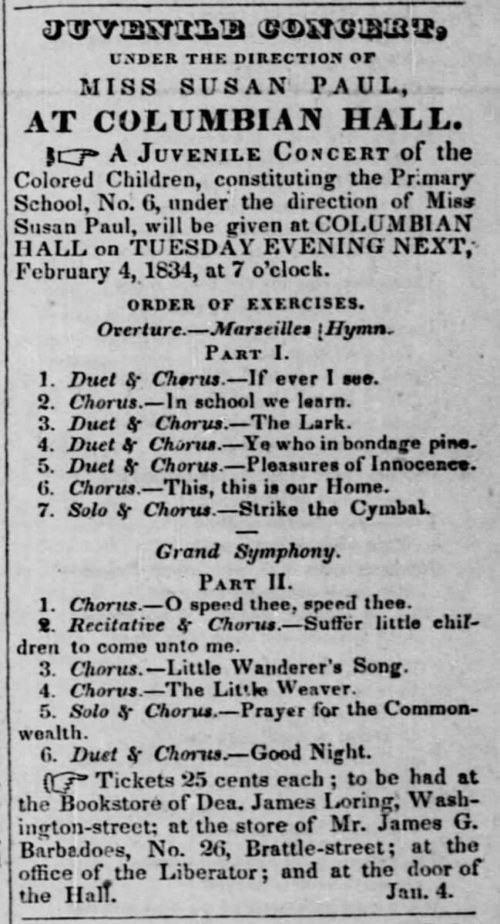

In addition to her teaching, Susan founded the Juvenile Choir of Boston for three- to twelve-year-old students which performed at many events and elicited wide praise for over two years. The children sang about the injustices of slavery and racism, the importance of education, and the privileges of being an American, at a time when the political discourse of the day typically excluded Black voices, especially those of children. The choir allowed Susan to showcase not only the talent and education of her Black students in front of integrated audiences, but provided her with a protective pulpit from which to extol her abolitionist philosophy, while still maintaining gender and race expectations of the day. Despite being free and living in the North, such public support of abolition could still pose a risk of violence for a woman, especially one of color.

In 1833, Susan became the first African American woman to become a lifetime member of the New England Anti-Slavery Society (NEASS); in fact the first performance of her Juvenile Choir of Boston took place at a September 1833 NEASS meeting. The following year Susan joined the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS) where she held officer positions, assisted in the annual Anti-Slavery Fairs, and represented BFASS in national anti-slavery meetings in New York and Philadelphia. Susan was also a co-founder of Boston’s first Black women’s temperance society.

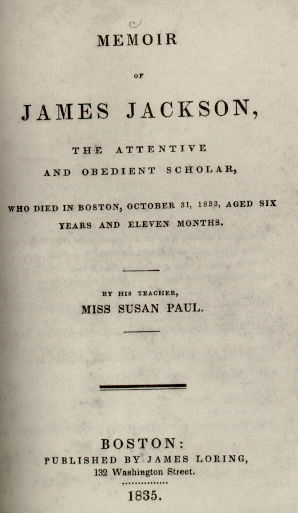

Susan published her only book in 1835, The Memoir of James Jackson, The Attentive and Obedient Scholar, Who Died in Boston, October 31, 1833, Aged Six Years and Eleven Months, the first non-fiction account of a free African American published in the United States. The book centered on James Jackson, a beloved student of Susan’s who died of tuberculosis, and his short life as a student of color in antebellum Boston as he grappled with the reality of slavery. In her writing, she highlighted the intellectual and moral character of African American children and their families, and implored readers to have the courage to “love anybody who is good” regardless of skin color. She wrote, “Let, then, this little book do something towards breaking down that unholy prejudice which exists against color.”

Later in Susan’s life she lived on Grove Street on the north slope of Beacon Hill. After her sister Anne died in 1835, she assumed responsibility for Anne’s four children, as well as her ailing mother, forcing her to gradually limit her public work. Tragedy followed Susan again in 1840 when her fiance died of tuberculosis; she would also contract the same disease In 1841, ultimately bringing about her death by consumption (the contemporary term for TB) at the young age of 32. Soon after her death, a letter in The Liberator honored her memory by printing, “many are abolitionists from the mere force of circumstances. Not so with Miss Paul. The simple fact that oppression existed was enough to call forth her most self-denying efforts for its overthrow.” Susan Paul is remembered today as a key female member of Boston’s Black abolitionist movement who bravely asserted the humanity of the enslaved, championed African American intellectual achievement, and devoted herself to the lives of her students and her community.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Baumgartner, Kabria. In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America. NYU Press, 2019.; Boston African American National Historic Site, https://www.nps.gov/boaf/index.htm; Brown, Lois. “Out of the Mouths of Babes: The Abolitionist Campaign of Susan Paul and the Juvenile Choir of Boston.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 75, no. 1, 2002, pp. 52–79.; Horton, James Oliver. and Horton, Lois E. Black Bostonians : family life and community struggle in the antebellum North / James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton Holmes & Meier New York 1999; Mitchell, Marcus J. “The Paul Family.” Old-Time New England, 1973; Paul, Susan. The Memoir of James Jackson, The Attentive and Obedient Scholar, Who Died in Boston, October 31, 1833, Aged Six Years and Eleven Months. Harvard University Press, 2000. Edited by Lois Brown.