The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was the Union’s first free Black regiment of the Civil War. The regiment, along with the Black 55th Infantry and 5th Cavalry, were deeply linked to the West End, from which they were advocated for, recruited, and organized. The 54th is memorialized in a bas-relief on Boston Common, and in the 1989 film “Glory.”

From it’s outset, the Civil War was fought over the institution of African American bondage in the American South. However, in the early stages of the war, before the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, few Black citizens had been allowed to serve in the Union forces. Many wanted to do so, motivated by the expectation – not yet official – that the war would determine the status of slavery in North America; the institution had been eradicated for moral, social, and political reasons across the European colonies in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Canada decades earlier. Black people had begun to serve under the Union flag as they were taken by Union forces penetrating the Slave States of the Chesapeake. These so-called “contraband” were used as army laborers, but were banned from combat, and remained abused by their liberators. In a few cases Massachusetts generals bucked this trend. Generals Butler and Freemont both issued general orders freeing the slaves in their respective zones of control. While both of these orders were rescinded by President Lincoln, they were emblematic of the Bay State elites mentality when it came to the war, and was extolled by Governor John Andrew, who began advocating for placing Black men in uniform close to the beginning of the war.

As soon as the Emancipation Proclamation had been officially announced, Andrew personally traveled to Washington, D.C. and convinced Secretary of War Stanton to authorize the recruitment of Black men in Massachusetts organized into special corps. Andrew rushed home with those orders in hand, and immediately began recruiting for the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment before the Secretary could have second thoughts.

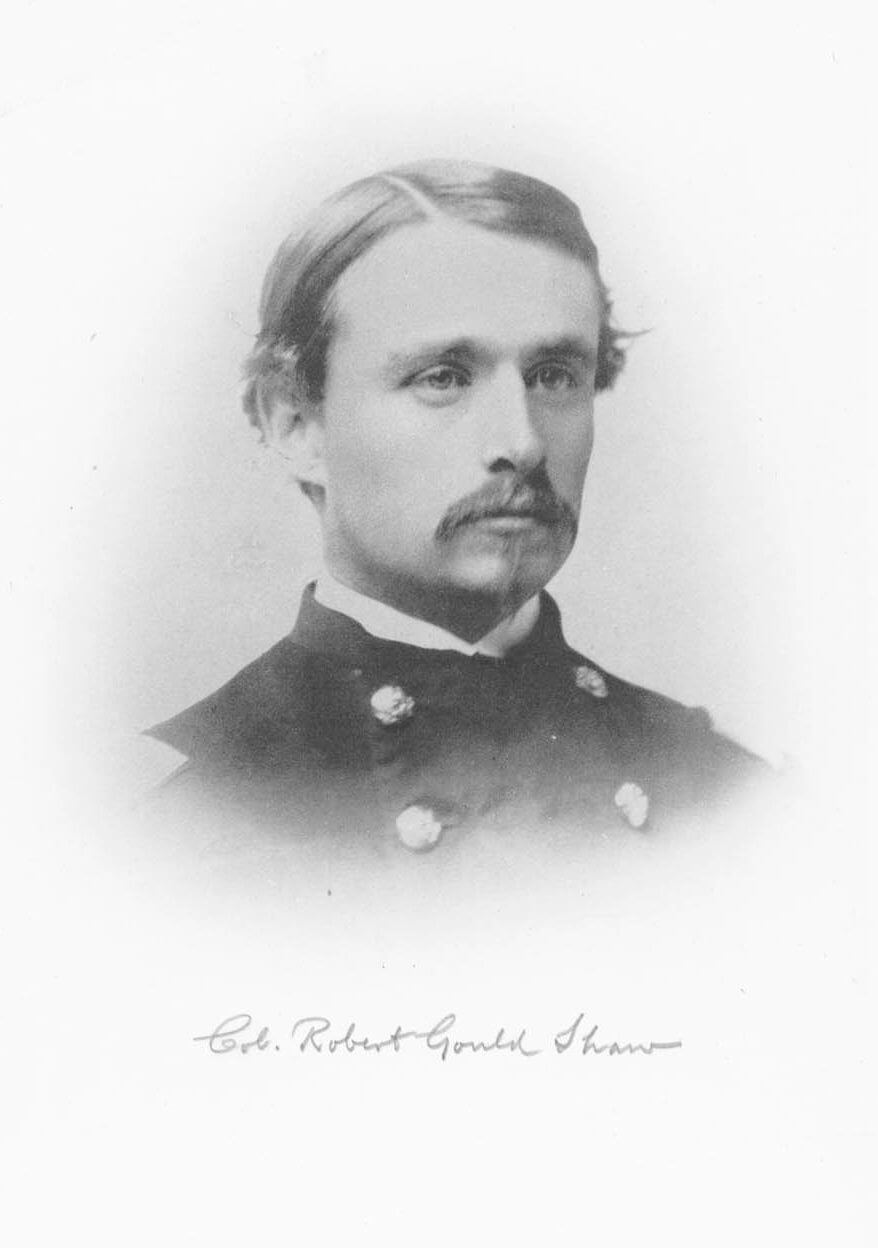

Recruitment of the 54th became a cause célèbre amongst the most prominent members of the Northern Black community. Prominent Black activists – including Fredrick Douglass, Lewis Hayden, William Cooper Nell, and Reverend Leonard Grimes – donated their time and energy to recruitment efforts. Douglass also gave his sons – Lewis and Charles – who both served in the 54th. Of course, support wasn’t universal. Some Black leaders, such as Robert Morris and John Rock, had reasonable objections based on the regiment’s leadership, which would be white. These objections were lessened, though not removed, once Governor Andrew had recruited a member of the prominently abolitionist Shaw family – Robert Gould Shaw – as the regiments colonel.

During recruitment Fredrick Douglass drew on the role Massachusetts had historically played in the effort for freedom, writing, “She was the first in the War of Independence, first to break the chain of her slaves, first to make the black man equal before the law, first to admit colored children to her common schools, and she was the first to answer with her blood the alarm-cry of the nation when its capital was menaced by rebels.” (Referencing the 6th Massachusetts, the first Regiment to suffer casualties in the war, and the first to reach an undefended Washington, D.C. at its outbreak.)

Recruiting centers was established in the West End at the corner of Cambridge and North Russell Streets, and in Haymarket Square, drawing a large number of men from the neighborhood. At a recruiting rally held at the African Meeting House, both Wendell Phillips and Edward L. Pierce spoke, imploring eligible men to enlist. Ultimately, the efforts of over 100 people went into recruiting for the 54th.

Those efforts started very locally, drawing scores of men from the streets of the West End into service. Nonetheless the process was slow. Perhaps unsurprising as the entire Commonwealth had fewer than 2,000 men who met both the eligibility and physical requirements to join, which were set very high. As a result, nearly a third of those who volunteered were rejected, and while the result created what one official referred to as “a more robust, strong, and healthy set of men” as were ever put into service, it also required recruiting across the Union, in places as far away as Ohio.

That fact bothered Ohio and New York, but it hardly mattered to Massachusetts, which began recruiting the 55th as soon as the 54th was full, and would eventually recruit a Black cavalry regiment, the 5th, as well.

In May 1863, just months after the order was given for their creation, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment marched in front of cheering crowds through the streets of the city of Boston ending their parade on the Common, across from the State House. Governor Andrew reviewed the troops and presented Col. Shaw with the regimental colors before they continued to Battery Wharf to board their ship to South Carolina. In the meantime, Andrew, Charles Sumner, and Shaw, among others, penned multiple letters attempting to resolve Federal pay and provisioning discrepancies between the Black and white regiments, which would persist for more than a year.

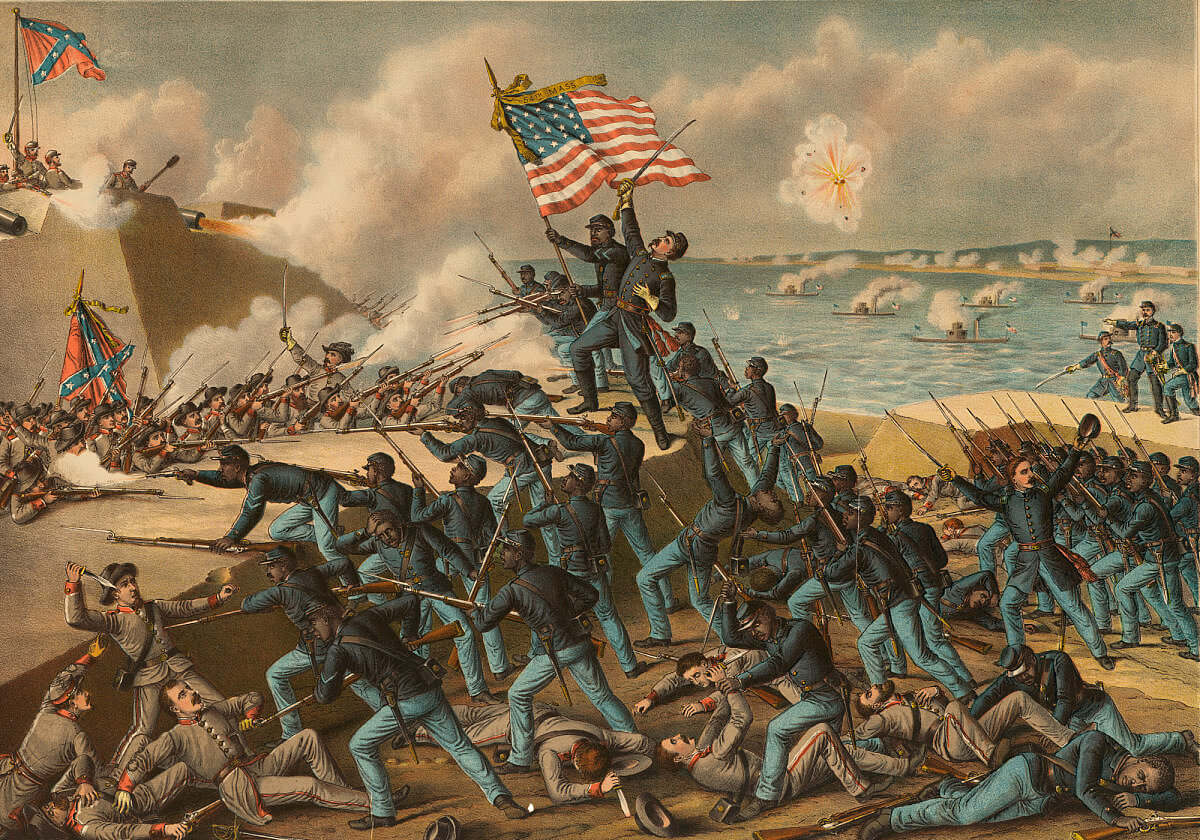

Not long after arriving in south Carolina the 54th was deployed to the siege of Fort Wagner at the opening of Charleston Harbor. Spearheading an assault on this key Confederate position, the regiment lost of nearly a third of their ranks, including Colonel Shaw (killed) and Lewis Douglass (wounded in the groin). Despite losing the battle, the bravery shown by the soldiers, including those from the West End, inspired the enlistment efforts of African-American men throughout the Union, and proved that Black men could serve on equal footing with their white counterparts. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a eulogy to the fallen soldiers in his poem Volunteers:

So nigh is grandeur to our dust,

So near is God to man,

When Duty whispers low, Thou must,

The youth replies, I can.

While members of the 54th recovered from Fort Wagner, others joined the 55th to fight near by at Honey Hill. The successful deployment and bravery of the 54th and 55th began a ripple effect throughout Union leadership. Soon, another Black regiment, the First South Carolina (the first made up entirely of former slaves) was raised and headed by another Bay Stater – Thomas Wentworth Higginson – and Governor Andrew began recruitment of the elite 5th Cavalry under Col. Shaw’s close friend Harry Russell.

The 54th continued fighting around Charlestown until February 1864, when they became the second Union regiment to enter the city. The 55th joined them 3 days later with Lt. Garrison, son of William Lloyd Garrison, amongst them.

With the close of the war, the 5th Cavalry deployed on the Mexican boarder to defend against a possible French invasion, but by the end of 1865 all three of the Black Massachusetts regiments were disbanded. Their legacy, however, had only begun to have its full impact. The pioneering efforts of the 54th, and the many Black regiments that followed, provided a basis from which not just military, but also civil service bloomed in post-war African American communities throughout the U.S. Over the next several decades Black men, many of them veterans, became political leaders in the North and the South. A handful became members of Congress, and many more took on positions of authority in local government, including as representatives of the West End in Boston. While many of these gains slipped away in the near-countless failings of Reconstruction, they provided a precedent that would be called on again as Black people fought for their rights, just as recruiters of the 54th had called upon the previous service of Black Americans in the Revolution and the War of 1812.

Article by Sebastian Belfanti and Marshall Hook

Source: Civil War Boston, O’Conner; Boston and the Civil War, Berenson; Frederick Douglass, Blight; Battle Cry of Freedom, McPherson; The Impending Crisis, Potter; The Republic for Which it Stands, White; Black Bostonians, Horton